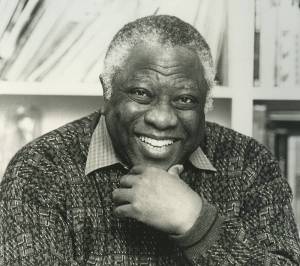

Twenty-five years ago this month, the Berlin Wall fell, and Woodie King Jr., founding director of the New Federal Theatre, happened to be there with a colleague. He wrote this reflection on his experience in 1990, and first published it in 2003 in his book The Impact of Race: Theatre and Culture. It is republished here with his permission.

Ten days after the restrictions between East and West Berlin were removed, I arrived in Berlin. Theatre work tends to set up unusual bedfellows. My meetings with Gotz Friedrich, director of Deutsche Opera Theatre, had been changed to Sunday, Nov. 20, 1989 at 5:30 p.m.. Thus, giving me and my American producer, Al Nellum, plenty of time to see Berlin or see the wall. A taxi driver who spoke no English—and, of course, neither Al nor I spoke nor understood an ounce of German—left both of us to speculate whether we Blacks could ever be international. We couldn’t even tell the driver to turn the heat on in the Mercedes Benz taxi. Laughter, then silence, as I speculate on the irony of how the Germans had turned the Mercedes Benz, America’s symbol of success, into a taxi cab. What the driver did understand was: Berlin Wall and Checkpoint Charlie. Upon our arrival at the West Berlin side of the wall were thousands of people. Already set up (in just nine days) were hundreds of vendors selling souvenirs, food, coffee and booklets describing the wall.

The wall was constructed Aug. 13, 1961. First it was a barbed wire structure built in an almost overnight act. The wall, a more solid structure, followed immediately. The irony of it all: The East Berlin Communist regime built the structure, jailing themselves. Now graffiti adorns at least 25 kilometers of the West Berlin side of the wall: Deutschland Liberta Boycott My Name Is Bundesprepublik. The graffiti blazes in hundreds of colors—large single letters, statements, distorted and abstract faces, all spray-painted like a long line of New York subway trains. Between the West Berlin and East Berlin wall is a 100-foot empty space, running the length of the two walls, appropriately called “No Man’s Land.” If anyone set foot in this area, he was shot on sight. The wall went up and the United States (and the West) did nothing to stop it. With financial support from America, West Berlin survived brilliantly; under democracy (capitalism) it moved out ahead of its East Berlin (socialist) brothers and sisters.

The wall was constructed Aug. 13, 1961. First it was a barbed wire structure built in an almost overnight act. The wall, a more solid structure, followed immediately. The irony of it all: The East Berlin Communist regime built the structure, jailing themselves. Now graffiti adorns at least 25 kilometers of the West Berlin side of the wall: Deutschland Liberta Boycott My Name Is Bundesprepublik. The graffiti blazes in hundreds of colors—large single letters, statements, distorted and abstract faces, all spray-painted like a long line of New York subway trains. Between the West Berlin and East Berlin wall is a 100-foot empty space, running the length of the two walls, appropriately called “No Man’s Land.” If anyone set foot in this area, he was shot on sight. The wall went up and the United States (and the West) did nothing to stop it. With financial support from America, West Berlin survived brilliantly; under democracy (capitalism) it moved out ahead of its East Berlin (socialist) brothers and sisters.

Now, 28 years later, on this cold Sunday morning, about 25,000 people have gathered at the Brandenburg gate where President Kennedy, flanked by Adenaur, Willy Brandt, and Raine Barzel, delivered his now famous (but then abstract) Ich bin Ein Berliner speech. Now, visitors and cameras witnessed and recorded the end of the wall and what it represented.

Of the estimated 25,000, Blacks numbered about a dozen. Many weren’t expatriates as expected, but Blacks from American countries, or journalists; about six were Black Americans. Why were we here? In my case as well as Al’s, it was an accident of history. Along this West Berlin side, as far as the eyes could see, people touched the wall. Small children with little picks and little axes pretended to chip pieces of the wall as parents snapped photographs; adults with large picks and large axes tried to chip. But the wall is built solid. Policemen apologized for having to ask people not to chip the wall.

I asked a German if I could use his hammer to break a piece of the wall. He waved me away, either not understanding or not willing to share his hammer. I placed both hands, with open palms, on the wall exactly as I once placed both hands on the cave wall in Goree, Ghana. I cried then; I tried not to but, caught in the emotion of the moment, I cried at this wall here in Berlin, West Germany. A lot of East and West Berliners were hugging and crying. At both the Brandenburg Gate and Checkpoint Charlie (where Soviet and U.S. tanks had confronted each other) thousands walked through freely, Vous Sortez du Secteur Americain (you are leaving the American Sector). I am witness; I was there.

This feeling, this look on the faces of East and West Berliners, were reflections of faces I’d witnessed during the Civil Rights Movement. I saw it on the faces of those of us who heard Martin Luther King Jr. speak in Detroit at the foot of Woodward Avenue in 1963 and again at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. in 1963’s poor people March on Washington. I’ve seen their faces in photographs after the decision in Brown v. Board of Education. I’ve seen their faces…

The irony of it all—this accident of history which brought Al Nellum and myself to West Berlin, which caused the National Endowment for the Arts to capitulate at this particular time, was/is one of the many results of Dr. King’s work finding further definition around the world 21 years after his death. Al Nellum, Hans Flury and Peter-Josephs Hargitay are in London producing King: The Musical, and I am coproducing it.*

The other director: the expatriate East German, Gotz Friedrich, director of Deutsche Opera Theatre. The teachings and words of Dr. King had impelled Friedrich to seek refuge in the West in 1966.