NEW YORK CITY: Over the past six years, the financial health of the arts has been in flux. Since the economic downturn in 2008, performing arts groups of every size and in every region have tried to determine how they are going to weather the storm. With funding contracting and working capital often dangerously low, many theatres have been struggling to stay afloat. Meanwhile, new questions have been raised about whether theatres are fully and accurately reflecting our diverse and changing world on their stages. Might the answers to these two challenges—fiscal and cultural—be integrally intertwined? Might theatres that are more culturally responsive and socially engaged also be the theatres that maintain a healthy bottom line?

That was one takeaway from the 2014 Theatre Communications Group Fall Forum on Governance: Cash & Culture. With more than 200 staff members and trustees from theatres across the United States gathered Nov. 7–9 in a Manhattan conference room, questions like, How exactly do we recover from the financial blows we’ve been dealt?, shaded into queries like, How can we reach wider audiences? How do we make sure that our theatres are representing their audiences and their concerns on their stages? The latter focus—on audiences and community engagement—is what finally swept the forum, turning it into a lively exploration of the hot-button issue of employment inclusion and diversity, onstage and off. (Videos of the conference are posted here.)

From the Ground Up

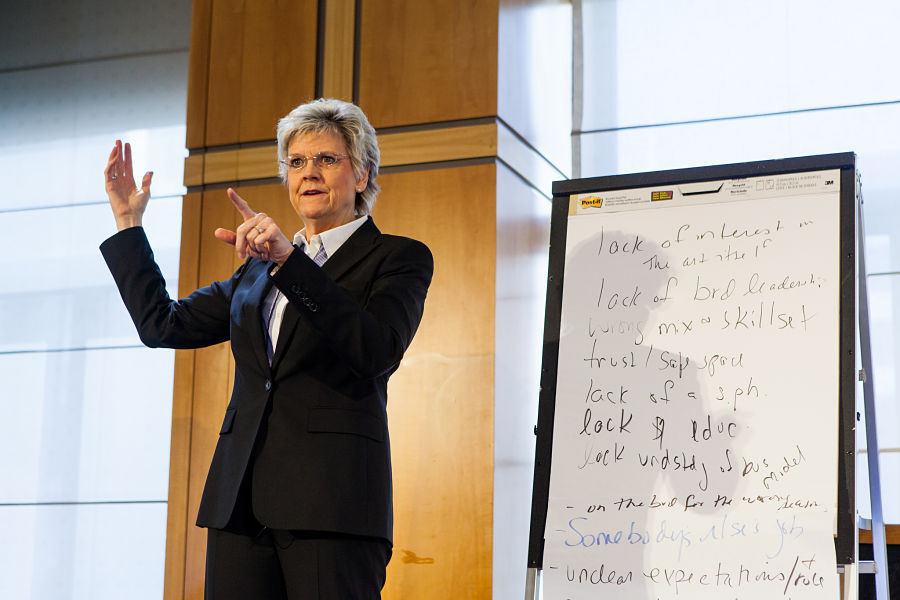

Kicking off Saturday morning’s sessions, Dr. Cathy Trower, president of Trower & Trower Inc., outlined the practices of successful theatre boards in a session titled “Best Practices for High Performing Boards.”

“The reason that so many boards underperform is that many board members have unclear expectations and do not understand their role,” Trower asserted, before opening the floor to questions and discussion. “Nobody’s talking about it, or about the issues, and everyone is too busy to see the problems.”

To address the situation, Trower suggested that theatres, in tandem with their boards, establish a mission statement that reflects the diversity and culture of the theatre’s audience. The board must also become self-aware about its own performance, and cultivate the ability to demand discourse and debate.

“Great boards help people confront values and beliefs, even if they are messy,” Trower said. “Critical thinking is hard, and we have a propensity to act, but part of great governance is staying with the problems longer.”

Persistence in meeting both business and interpersonal challenges was a recurring theme during the three-day forum. With so many theatres and performing arts groups struggling financially in recent years, learning how to restructure and rebuild a broken theatre business model was another hot topic. Susan Nelson, principal at the Technical Development Corporation, covered the latter concern in her session, “What is Your Critical Capitalization Challenge?”

“All capital is not equal—everyone’s challenges are different,” Nelson asserted. “You can’t approach this in a cookie-cutter way—you have to understand your specific needs.”

Nelson defined capital as “having the cash to do what you want when you want to do it.” To achieve that status, organizations must cultivate the ability to invest in the art they produce and have a clear overall vision of where they want to go.

“I know we’ve been searching for the ‘nirvana’ business model, and we know someone out there has it,” Nelson said. “And when we do have it, we’ll tell you. Until then, we’ll have to keep looking.”

Though Nelson didn’t pretend to offer a silver bullet for ailing theatres, she was not afraid to say exactly what needed to be said to the people in the room. “The biggest risk is that we’re working with a broken business model, and we don’t want to confront it,” she said. “Fixing it is the only option.”

The Comeback

For many of the theatres and groups in the room, the notion of a complete overhaul prompted anxious looks and troubled conversations. It was only after a number of groups took the podium to relate success stories about putting dire financial situations behind them that some of these fears were calmed.

Speaking from their own experiences, Michael and Sade Lythcott of New York City’s National Black Theatre, Ken Novice and Pamela Robinson of Los Angeles’s Geffen Playhouse, and Steven N. Miller and Chay Yew of the Victory Gardens Theater of Chicago talked about how they were able to bounce back from financial difficulties following changes at their theatres, and the impact that recovery has made on their staffs and audiences.

For the National Black Theatre, it was the sudden death in 2008 of the company’s matriarch, Dr. Barbara Ann Teer, that set a series of drastic changes in motion. But because of strong community support, the theatre was able to rally and become stronger than ever.

“Where we have had challenges, we feel fortunate in our inheritance,” declared Sade Lythcott, NBT’s CEO. “For us, social issues and social justice are at the forefront of what we do, and if the theatre works, it’s because the community has worked with us.”

For Victory Gardens it was smart business sense and teamwork that led the company out of the woods.

“We’ve been able to really work together as a team to get the theatre healthier,” reported Miller, president of Victory Gardens’ board of directors. “We ended last year in a surplus, which was not in our vocabulary!”

At the Geffen Playhouse, old debt was retired, which opened new doors for programming that brought new audiences in and old ones back.

“We were sitting with renovation debt when I came to the Geffen in 2009, and we worked on retiring it—we did that three years ago,” noted Novice, the Geffen’s managing director. “Now, we feel like we want to set the theatre up for the next 20 to 30 years, and we’re now in the process of creating an endowment.”

The minutiae of the business side of things were initially the main topics among conference participants. But as the conversation took on more depth and more complex questions emerged, the discussion turned into more of a dialogue among the panelists about what kinds of programming actually get audiences in the seats. Though this is not a question with easy answers, the conversation seemed to resonate with the attendees.

Victory Gardens artistic director Yew said he approached the challenge by exploring such questions as what it was about Chicago that struck him, and how to define theatre in the 21st century, since standards change over time. Through that process, Yew asserted, he is learning what it means to “give theatre back to the people of Chicago,” and what his audiences want to see.

For the Geffen, the situation was similar, according to Robinson, the board co-chair. “You embrace the culture, and you embrace the heritage, but you have to tweak it for new audiences,” she said. “It’s an exciting time when you can keep the heritage but make it new.”

To end the day, Teresa Eyring, TCG’s executive director, posed a series of four questions for the audience to answer as homework for the next day’s discussions. Each participant was asked specifically what information they’d gotten out of the day’s programming, and what they might possibly take home with them to share with their theatre. When these questions were presented to the floor for discussion the following morning, it was clear that the ideas of the previous day had struck a chord with almost everyone.

Paying It Forward

The conference’s Sunday morning sessions were permeated by the feeling of a chapter in an ongoing story coming to an end. After spending three days with the same group of people, it was clear that bonds had been forged and new relationships begun. The ultimate question, though, seemed to be: What exactly do we take home with us as a plan of action?

The answers varied; they were large in number and rich in detail.

“At this point, we are still trying to find our sea legs, but we are going to start immediately, when we get back, using notecards to map out further discussion,” said Mindy Elmer, board president of the ZACH Theatre in Austin. “I would like to have a few years of plateau before we move up any further, and I don’t think our board understands that, so we‘re going to take these questions back with us.”

Communication among board members and staff was a hot-button topic not only for ZACH but for many other theatres, as was the restructuring of programs that could simultaneously make financial sense and entice audiences.

Childsplay in Temple, Ariz., looked back at what they had been doing in past years and reimagined it, reported Steve Martin, the company’s managing director. Every program Childsplay does goes through this process, and every production has artistic goals that will fuel both the company’s explicit mission and audience development. Now, Martin said, they are going through a strategic planning process to project where they want to be in the next five years.

The conversation shifted to how to deal with problems of leadership in the theatre, as Eyring led an impassioned discussion with a panel that included Ben Cameron, program director for the arts at the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; Barbara S. Davis, chief operating officer at The Actors Fund; Kelvin Dinkins Jr., general manager of New Jersey’s Two River Theater Company; Victor Maog, artistic director of Second Generation Productions (2g) of New York; TDC’s Nelson; and Vicki Reiss, executive director of the Shubert Foundation.

The panelists took questions from the audience about conditions that are currently challenging their fields, such as new ticket sales methods, finding and supporting new artists, establishing a firm funding foundation and reaching out to individuals and groups who may not see themselves represented onstage. Their responses opened up the floor for an honest, heartfelt conversation about what it takes to navigate the nonprofit theatre business today, and what changes theatres and organizations might be able to implement based on takeaways from the Fall Forum weekend.

Help an Artist, Change the World

In a room full of theatre people, everyone has at least one thing in common: Both artists and administrators are facilitators of artistic practice. The starving artist may appear as a romanticized figure in popular culture, but for many in the theatre, it is a reality. With budget cuts so common in recent years, it has been extremely difficult for organizations to support their resident artists and to reach out to new ones—a trend that can lead up-and-coming writers and performers away from the theatre. But according to some conference attendees and panelists at the closing Sunday session, there are ways around that financial hurdle.

“Every day at the Actors Fund, we try to think of ways to help artists stabilize themselves,” noted David. “What we have found is that there are challenges to making our services available across the country, there are a lot of other things that relate to basic needs, and people’s attitudes about money, and where they’re going to make changes. Being a starving artist doesn’t always feel as good at 45 as it did at 25.”

This is why, the panelists suggested, it is so vital to support newcomers to the business. “We can’t bring young people into the theatre if we’re not seeing them,” said Nicki Genovese, head of the theatre management program at Cal State Long Beach. “We have the conversation all the time about, Where are the applicants who don’t look like me? If you know students who are considering pursuing education, or going into something else that will deepen their experience, enrich their skill sets, please send them to schools and programs and MBAs and MFAs, accreditation programs, because we wonder where they all are; we’re not seeing them. We can’t bring about diversity in the field if we can’t get them in our doors and then get them to your doors.”

People (Not) Like Me

Over the weekend, the conference room also became a safe haven for conversations that might be too contentious elsewhere. Topics of race, culture and gender in theatre were broached with emotion and intensity, yet in a calm and collegial manner. And it became clear, thanks to several instances of personal testimony, that, while there may have been significant progress made in diversifying the theatre in recent years, there is still a long way to go.

“I have gotten a degree in the field, and have been schooled in it—but to look around the room and not see people like me is wrong,” asserted Dinkins, who is African-American. “To be intimidated by this field because of my age and because of how I look is wrong. With all the classes I have taken and all the qualifications I have, I’m still afraid I won’t be given a chance at all.”

The subject of the Rooney Rule—a practice of the National Football League that requires interviewing candidates of color for head coaching and senior football operation jobs—came up. The general sentiment expressed was that if a candidate is qualified, their race, gender or ethnicity should not be a factor when it comes to hiring. Still, as default white privilege still predominates in the theatre as in the larger culture, some leaders see the value of a Rooney Rule–style mandate.

It was Madeline Sayet of AMERINDA Inc. who made the clearest statement of purpose in this vein. “In the theatre, I never see people who look like me,” Sayet testified. “And after you walk into a room and they tell you, ‘You don’t look Native,’ how many more times do you want to walk into a room and be attacked?” The fear of rejection and the need for acceptance was a common thread, which coalesced into a strong call for change.

Putting It All Together

At the beginning of the weekend, there was only a vague notion of what would happen over the course of the next three days. By the end, attendees walked out of the conference room confident they could go back to their theatres with tools that would help them stabilize their organizations, reach new audiences, and perhaps help change the theatre world in the process.

Eyring confessed that when playwright Robert O’Hara (Antebellum, Bootycandy) delivered the Forum’s opening address on Friday night, declaring, “‘Cash and culture’? I am not going to talk about anything TCG told me to talk about,” she was worried. Then O’Hara said, “When I think of cash and culture, I think of old white men, and so tonight I am going to talk about old white men,” and Eyring became even more worried.

But O’Hara proceeded to talk about how his career trajectory was positively affected by “old white men,” and how he hopes to grow old with his life partner, who fits that description, as well. It became apparent to Eyring that O’Hara had done what all great artists do—he’d created “a space where something new was possible.”

In that space, she continued, “We can acknowledge the ongoing impacts of racism, sexism and homophobia, all those walls that continue to divide us and our capacity to take care of each other across those borders of identity. And usually that’s the case with those ‘uh-oh, oh no’ moments—it means that things are more complicated than you thought, but it also means that more is possible.

“It means we can make something new,” Eyring said in her concluding remarks. “And that’s where we’ve been over these past few days together, experiencing those ‘uh-oh’ moments, acknowledging that things are more complex than they used to be, and reaching together toward something new.”