It’s early November, the final week of the month-long Encuentro 2014 Latino theatre festival, and José Luis Valenzuela is a fixture in the bustling lobby of Los Angeles Theatre Center. Latino Theater Company’s artistic director and his company have operated the five-theatre downtown complex since 2006, and it’s safe to say they’ve managed to turn the place around after years of neglect. Valenzuela has also managed to make it a kind of national beachhead for Latino theatre work—at least, that’s part of the thinking behind Encuentro 2014, produced by LATC in association with Latina/o Theatre Commons, a division of HowlRound.

It has been a long and bumpy road to this desination. Los Angeles Theatre Center’s storied, even notorious history began in the economically flush 1980s, when a $14–million facility was created in this abandoned, five-story 1917 Security Pacific Bank building. (Audiences can see the original bank vault, a vintage artifact, in a subterranean passage on their way to the restrooms.) Its lobby remains a cavernous echo chamber, impressively refurbished since its days of decay after a former administration, headed by Bill Bushnell and Diane White, ran aground in October 1991, in a flurry of unpaid salaries and bills.

Grubby carpeting has been replaced with buffed hardwood floors. Dozens of feet into the sky, ornate, metallic art deco panels form the lobby ceiling. A stairwell with a long upper ramp leading to upstairs theatre entrances and administration offices sweeps down to the main floor, like a setting straight out of Gone with the Wind.

Encuentro’s official “coffee sponsor,” Don Francisco’s Coffee, has a station at the lobby’s center, grinding out complimentary lattes and cappuccinos for festival participants and audiences. Yet the buzz from all the free coffee in the world can’t stave off Valenzuela’s tired expression, sneaking out from behind receding silver hair and a goatee. Perhaps it’s the toll of running this ambitious festival. Perhaps it’s the toll of holding his Latino Theater Company together for 30 years. Perhaps it’s the toll of operating LATC. (For his day job, Valenzuela heads the directing program at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film and Television.)

Valenzuela has good reason to show a little battle-weariness. After Bushnell and White “left the building,” it then sat virtually dormant and leaderless for years. Valenzuela’s struggle for control of LATC began in 2005, when his bid to the city came in second behind the winning bid of downtown developer Tom Gilmore (partnered with Shakespeare for youth troupe Will & Company) to present for-profit performances while leasing some of theaters to non-profit troupes. It was a rude rebuke to Valenzuela, whose Latino Theater Company (originally the Latino Theatre Lab) was born in 1985 as one of LATC’s resident projects during the Bushnell/White regime. Because of Valenzuela’s complaints that Los Angeles had no institutional theatre serving the Latino population (soon to become a statistical majority in Los Angeles), the city initiated a new “Request for Proposals” initiative from scratch.

As a result, the city ordered Gilmore, the principal tenant, to share the facility with Valenzuela and Will & Company—which they did, tempestuously. Valenzuela and Gilmore soon started feuding over who would call the shots, with Gilmore claiming that Valenzuela simply wanted him out. It was a mini-race war played out within and over the occupation of a theatre.

Ultimately, Valenzuela’s team pulled in support from the city’s then-mayor, Antonio Villaraigosa, along with state politicians. The city ordered a new Request for Proposals, and in 2006, Valenzuela and a new partner, the Latino Museum of History, emerged as victors, with Latino Theatre Company contracted to operate the building’s theatres for 20 years, and the museum signed on to be in residence throughout the building’s subterranean space.

But the troubles weren’t over: By 2009, the theatre and the museum were feuding with each other over alleged breaches of contract. In January 2012, the city served both Latino Theater Company and the Latino Museum of History with eviction notices, essentially telling them to take their fight off city property. The city also alleged Latino Theater Company had failed to keep basic accounting information, charges that Valenzuela successfully refuted.

The museum is now off-site, and Valenzuela’s Encuentro 2014 festival is in full swing. The lobby hasn’t been so animated with crowds since the days of Bushnell and White.

The Man in the Middle

At the middle of it all stands Valenzuela, an immigrant from Los Mochis, Mexico, looking somewhat victorious but also clearly exhausted from decades of victories and woes, both largely of his own making. Like Chekhov’s Yermolai Lopahkin, the grandson of serfs, he stands clutching the keys of the estate he just bought—except that Valenzuela has been so distracted lately, he confesses, he doesn’t have his keys with him. This is why he’s now waiting by a lobby elevator for a security guard to let him into his own office.

His battles are a microcosm, an allegory, for Latino theatre in general, perhaps for Latino culture itself. Like a Chicano Rodney Dangerfield, between Valenzuela’s words, you can almost hear an echo of Dangerfield’s “I don’t get no respect,” but with a pivotal variation: “We don’t get no respect.”

“We were not part of the conversation,” Valenzuela explains from his second-floor office. “We [created Encuentro 2014] because we don’t exist. We’re not part of the narrative of American theatre.”

Encuentro 2014 was born in 2011 in the aftermath of the first Theatre Communications Group conference ever held in Los Angeles. Valenzuela attended, and says he was struck by the absence of any discussion or concern about Latino theatre at the nation’s most prestigious national convening of theatre professionals.

Valenzuela asked some attendees of the 2011 TCG conference to stay on for an extra day to discuss the status (or rather lack of status) of Latino theatre in the United States. As a result of those conversations, in May 2012, at the behest of playwright Karen Zacarías, HowlRound hosted eight theatre practitioners in Washington, D.C. Thus was HowlRound’s Latina/o Theater Commons born. At a much larger meeting in November 2013, at Emerson College in Boston, Valenzuela expressed the desire for a festival, to redress the problem that so many Latino creators have no idea what their colleagues’ work looks like.

A prominent arts advocate repeated the commonly held view that they were “nuts” to try to put on a national festival with less than a year’s notice. Yet by October 2014, Valenzuela and company had secured the support of the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the James Irvine Foundation, L.A. City’s Department of Cultural Affairs, Time Warner Cable, the Ford Foundation, the Los Angeles County Arts Commission, Southwest Airlines, Union Bank, Wells Fargo Bank, the Boeing Company, the Ahmanson Foundation, 20th Century Fox, 21st Century Fox and Goya Foods, to name just a few. Valenzuela is nothing if not tenacious.

Ten Latino performance companies were invited from 75 applicants. They came from Puerto Rico, New York City, Denver, Los Angeles and points between. Including readings and off-site presentations by local companies, the festival, which ran between Oct. 10 and Nov. 12, comprised 19 presentations in all.

The festival was designed to put the work at the center. Its first mission was not to integrate Latino theatre into mainstream theatre culture but to acquaint Latino/a artists with each other and their work; this festival was to be about and for the artists. The second directive was that attendees wouldn’t be there to hash out politics, identity or otherwise, prevalent and threadbare as these themes have become, but rather to discuss the work and its aesthetics.

But What Makes It Latino?

This kind of colloquy is precisely what occurred at Encuentro 2014’s post-performance discussions. Artists from the company whose work had just been performed sat onstage, joined by respondents from another company. After a response—generally enthusiastic, but sometimes asking probing questions about the reasons behind certain creative decisions—other festival attendees were invited to respond and/or ask questions. By design, the festival included a range: playwright-driven works, ensemble-driven/devised works (some experimental) and solo performances. In other words, a lot like the profile of much nonprofit theatre across the U.S.

What, then, makes the work Latino? Where resides a specific Latino identity? The politics tend to be embedded in the work, in stories of families wrenched apart by immigration policies, of one young man in Honduras trying to crash through the U.S. border to see his mother, who left him behind when he was a child. They reside in stories of continental divides between the U.S. and Puerto Rico and Mexico, between husbands and wives, between suitors trying to connect across the seas via the Internet, in stories of people feeling isolated in the world’s most populated cities.

And, of course, Latino identity resides in the language, in the bifurcations and intersections of English and Spanish and Spanglish, in the cadences and the attitudes, the ebullience and the heartbreak they convey.

Representing the experimental wing, Caborca Theatre brought its production of Zoetrope: Part I. The NYC-based company started working together at the University of Puerto Rico in 2002, before continuing their work at Columbia University. Their leader is writer/director Javier Antonio Gonzalez, whose play tells the story of a wedding in 1952 Puerto Rico (the play spans four decades) and its subsequent unraveling when the groom, Serevino (Marcos Toledo), joins the U.S. Army and winds up settling there for the income from a job in a mailroom. Meanwhile, his bride Inés (Laura Butler Rivera), teaches English in Puerto Rico, wrestling with her loneliness and with reports of her husband’s infidelity.

This somewhat traditional soap-opera narrative is woven into a kind of anthem for revolution—with the subtle defiance of the local priest, with women assuming power in domestic partnerships, with Inez’s sister, Francisca (Tania Molina) being not particularly interested in men, and with Puerto Rico’s continued ache for independence from the United States.

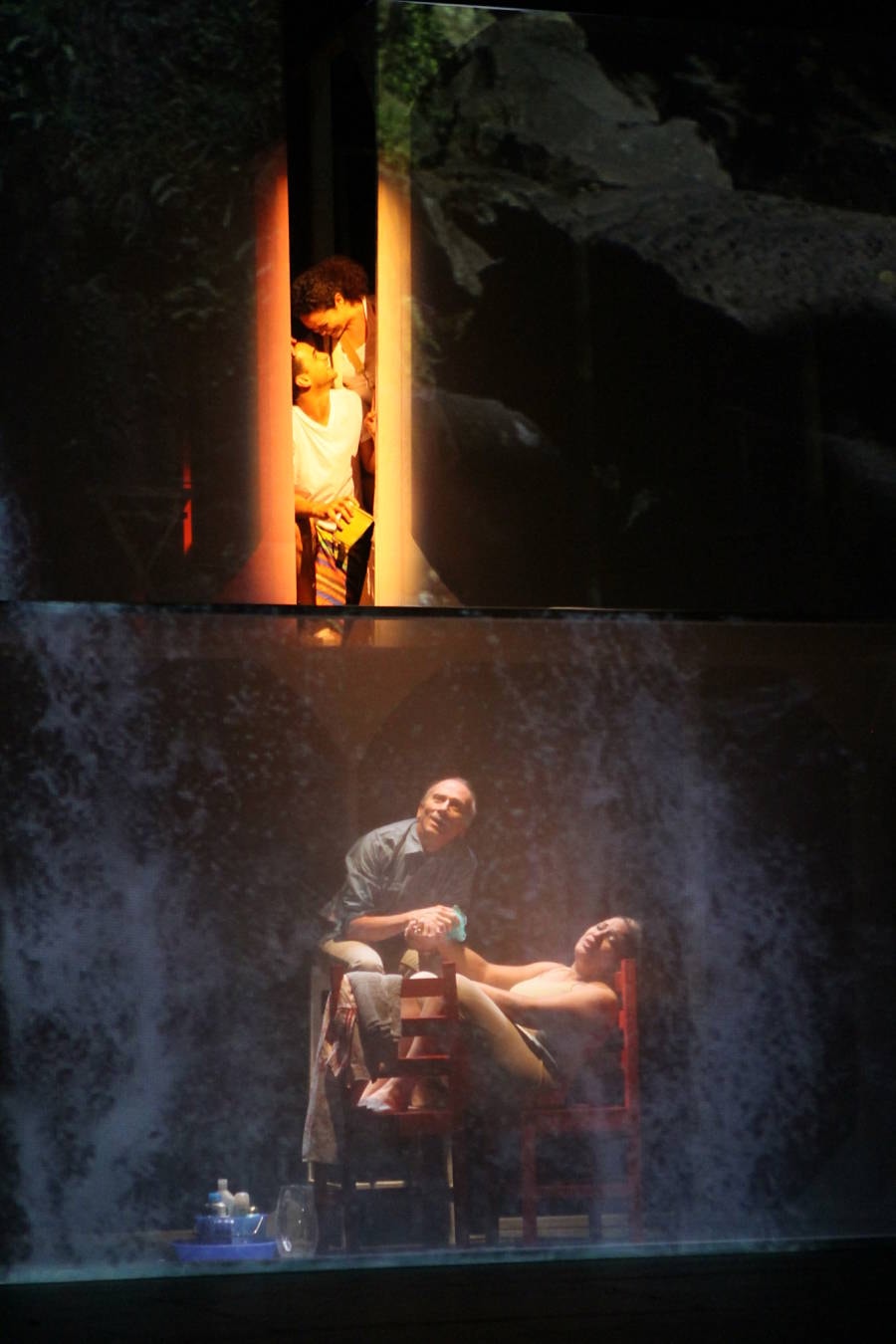

The storytelling employs a heightened, Brechtian theatricality, which some audiences have found frustrating. Gonzalez takes his cue from the Wooster Group and Britain’s Forced Entertainment, keeping costume racks and props visible on the stage, having the actors change clothes in full view, while an onstage videographer (Timothy French) follows them around, allowing their intimate scenes to be projected onto a wall.

While others were frustrated by missing links in the variegated plot, I found this element to be the production’s virtue, in that it allowed us to fill in the dots of the characters’ emotions and of the play’s meaning. The bilingual performance flipped supertitles between English and Spanish. Meanwhile, the actors slid between languages with similar ease. Conceptually, I can’t think of a better way to show the divides at the heart of this absorbing and beautifully enacted saga.

Hudes, Chibas, Gonzalez and King

The most looming accomplishment of Quiara Alegria Hudes’s 2012 Pulitzer Prize–winning drama, Water by the Spoonful (Agua a Cucharadas), is the play’s seamless blend of microscopic and macroscopic dramas. (This was L.A.’s first chance to see the play, thanks to Puerto Rico’s Tantai Teatro PR, in Laura Martinez’s Spanish-language translation; oddly enough, we were reading Hudes’s original English dialogue in the supertitles.)

In Philadelphia, wounded U.S. Marine Elliot (Hiram Delgado), who makes sandwiches at a Subway, goes off the rails when he learns that the beloved aunt who raised him is dying. (Elliot is the central character in a trilogy of dramas by Hudes, but this one certainly stands alone.) Elliot’s confidant and best friend is his cousin Yaz (Yinoelle Colón), a music-theory professor who appreciates the artistry and wisdom in the seeming chaos and noise of John Coltrane’s music.

The drama of Elliot’s frustration with Odessa (Aidita Encarnación), the birth mother who gave him to her sister to rear, would suffice for a stock domestic drama. But Hudes juxtaposes this story with the onstage depiction of an international online chat room, a support center for drug addicts—five translucent boxes, high and low on the stage, through which the characters, sitting at monitors from Philadelphia to Puerto Rico to Japan, appeared typing feverishly while speaking their online repartee. This is moderated by Mamahaiku (also Encarnación), who deletes curses and keeps sarcasm and abuse at bay, or tries to.

The coy attempt of one black American participant (Willie Denton) to find his way to Japan, at the invitation of “Orangutan” (María Bertólez), underscores the attempt to circumvent pathological isolation in our tech-savvy world. And that Wendel Agosto’s set should so wholly box the characters in was paradoxically anti-theatrical—and precisely the point. How do we push beyond the frames of our screens in our quest for something human? Ismanuel Rodriguez directed a first-rate ensemble, playing out Hudes’s beautiful, expansive spectacle.

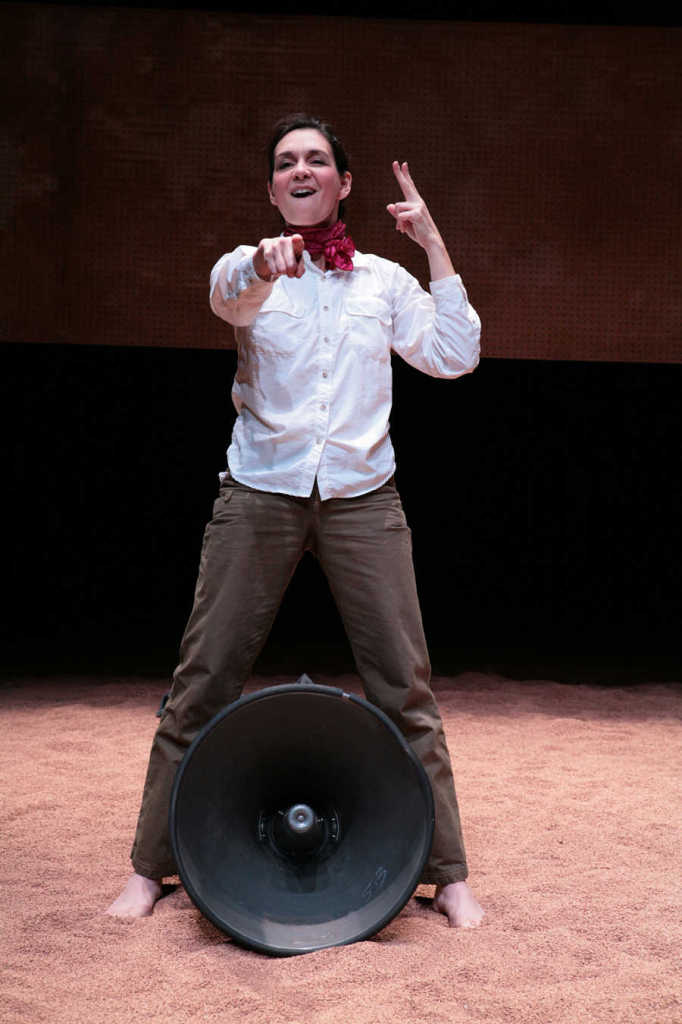

In the solo show category, CalArts Center for New Performance presented writer/performer Marissa Chibas’s Daughter of a Cuban Revolutionary, a relatively straightforward daughter’s narrative about her dad, in this instance Raul Chibas. Her father’s claim to fame was co-authoring Fidel Castro’s manifesto on democracy, then fleeing Cuba after suggesting to Cuba’s chief-executive-for-life that the country might be improved by sticking to the tenor of that manifesto. Does it demonstrate courage or mere folly to advise Fidel Castro not to behave like the dictators he replaced? Mira Kingsley directed the gentle production, through which the politics flickered in the vapors of memory and history—same thing, really—with a knowing tone, slightly sardonic and shrugging, as if to say, Well, that’s the way things go.

Writer/performer Ruben C. Gonzalez’s solo performance La Esquinita, USA came from one of Latino theatre’s legacy companies, El Teatro Campesino of San Juan Bautista, Calif. Luis Valdez’s troupe was originally a wing of the United Farm Workers. His son, Kinan Valdez, directed Gonzalez, a mercurial, silver-haired writer/actor who slid effortlessly between portrayals of multiple denizens of a fictitious American city where the burg’s economic engine, a local tire factory, has picked up and moved to China, leaving behind an old brick building with wind howling through its empty rafters, a bus line running on a dubious schedule and an array of meth addicts and dealers. Gonzalez’s performance was first-rank in a poetical two-act play still in need of editing.

Meanwhile, NYC’s INTAR (Unit 52) presented Mariana Carreno King’s Patience, Fortitude and Other Antidepressants, a Puerto Rican family drama concerning a painter/frustrated housewife (her husband has, ahem, “performance” issues). He’s a possessive cop who overreaches to keep the peace, while his own obnoxious clan moves in and takes over his wife’s private space. Some pleasing ensemble work unfolded in a play written in broad strokes, and directed by Daniel Jaquez.

Other Voices, Other Reasons

In Dancing in My Cockroach Killers, Pregones + Puerto Rican Traveling Theater presented director Rosalba Rolon’s adaptation of Magdalena Gomez’s sometimes lyrical, sometimes pedantic poems—recitations and chorales seamlessly accompanied by a live band in seductive tones.

Su Teatro, a community theatre from Denver, brought adapter/director Anthony J. Garcia’s staging of Enrique’s Journey, based on Sonia Nazario’s Pulitzer-winning writings in the Los Angeles Times about a Honduran youth’s efforts to join his mother in North Carolina. It follows multiple attempts by Enrique (Jose Guerrero) to bust across the Rio Grande after being hounded by “coyotes,” betrayed by his compatriots, and being almost left for dead in the Mexican desert. Equal parts chastening and sentimental, this comparatively literal production was the festival’s biggest crowd-pleaser.

Last but not least, José Luis Valenzuela’s own faux-noir staging of Evelina Fernandez’s farce Premeditation, a production of his own Latino Theater Company, flowed like silk. In it, a frustrated housewife (Fernandez) hires a hit man (Sal Lopez) to off her UCLA professor husband (Geoffrey Rivas) because he leaves his underwear on the bathroom floor. After hearing this explanation in the hotel room where they’re planning the hit, the assassin takes a long, considered pause before blurting out his concern: “I need another reason.” He’s feeling empathy for the would-be victim, having problems of his own with his sharp, loud wife (Lucy Rodriguez).

And so, in a roundelay of misunderstandings and misperceptions based on faulty presumptions, the four characters literally spun across the stage—with the furniture, with lampshades and chests of drawers, via Urbanie Lucero’s choreography. Meanwhile, Lopez’s physical comedy ranked with that of Cantinflas and Costello.

One respondent in a post-play discussion remarked that, having been together for 30 years, Latino Theater Company is among America’s great ensembles. Given the evidence on the stage, there’s truth in that claim.

Despite Valenzuela’s stated mission of presenting a festival specifically for Latino artists, and more generally for Latino audiences—a chapter out of August Wilson’s “Ground on Which I Stand” playbook—his own production, with its polish and almost classical-European dramaturgy, reaches convincingly into the “mainstream” of American theatre, taking a chapter from the playbook of another legacy Chicano company, Culture Clash, which has for two decades been doing much of its work in and for America’s major nonprofit theatres. This has both aesthetic and funding reverberations. It’s as though Valenzuela is doing the tango on two different dance floors at the same time: one in Washington, D.C., and one in East L.A. It’s a delicate, nimble dance, but he’s been doing it for years.

Premeditation also puts to rest the prejudice that Latino theatre, being essentially insular and communitarian, isn’t really worth discussing. After 30 years of scrapping, Valenzuela insists that it is. His own theatre—and the Encuentro 2014 he gathered around it—have made the case.

Steven Leigh Morris is the theatre critic for LA Weekly, and the founding editor of StageRaw.com. He is also a playwright.