One week in the late ’90s I was in Nashville, crashing on the couch of a friend, the songwriter Sam Lorber. Back then I made fairly regular sojourns to Nashville to write country songs. It was tornado season—the skies were black and threatening, the power intermittent. The phone rang and Sam’s wife Joan went to answer it. I heard her speak, then she walked back into the room, pale-faced, a bewildered look in her eyes: “Amanda, Lauren Bacall is on the phone for you.”

Betty, as her friends called her, was an old family friend. She knew of my deep love for singer Lyle Lovett, whom she befriended when they appeared together in the film Prêt-à-Porter. She was calling to invite me to accompany her to one of his concerts in NYC.

A week ago, when I found out Bacall had died, I e-mailed Sam and asked him if he remembered the incident. “Are you kidding?” he replied, “It is Joan’s moment of stardust. Never to be forgotten.”

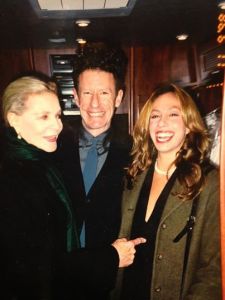

Betty not only took my husband and me to that concert; she brought us onto Lovett’s tour bus beforehand, where we had a private chat before his show. It was a magical, pinch-me moment. Always, with her, we were the eye of the storm; seas parted and people gaped as we made our way down the aisle. At intermission I pushed my luck. I had brought a cassette of a few of my songs. I nervously asked Betty, “Do you think I can give this tape to Lyle?” She replied with shock, “Oh really, Amanda! That’s going too far!” “Well then, I suppose sleeping with him is out of the question,” I replied. “Oh REALLY! Amanda!” My husband and I dissolved in giggles. “Fresh!” she barked, then laughed, too.

Still, she was a loyal and proud supporter of my work, gamely showing up, from early showcases at the Duplex and 88’s to my first Broadway opening. Betty was there like a proud aunt—a proud, world-famous, impossibly glamorous, hard-boiled, loving, movie-star aunt.

My brother Adam wrote a spot-on remembrance of Betty for Vogue; being siblings, we share many of the same memories. Like him, I have a vivid memory of calling her “Lauren” as a five-year-old—my first experiment in calling a grownup by their first name. Why I chose her to begin with, I’ll never know. I walked into the library where she and my parents were sitting and said, “Hi, Lauren!” They burst out laughing, and I blushed and hid my face in the sofa cushions.

I remember also at that age being backstage at the Palace Theatre with my family in Betty’s dressing room after a performance of Applause, for which my dad and Betty Comden wrote the book. I felt I was in the epicenter of the universe. She was laughing, gracious and holding court.

My dad was friends with Betty from the early days, and she and my mom took an instant shine to each other when they eventually met. Mom says my dad would drop in often and uninvited to her and Bogart’s home, hanging around as much as they’d allow. “Jesus, Adolph! Go home already!” was a familiar cry of Betty’s. But she adored him, and he adored her. Their friendship deepened and grew over the years. Christmas, New Year’s, birthdays, anniversaries, weddings, funerals—all moments our families marked together.

Betty was, of course, incredibly, famously intimidating, but she only occasionally scared the hell out of me. Early on, I intuited that there was no venom in her sting when she got sharp with me, and I learned to give back as good as I got. At one memorable summer wedding I attended in my early 20s, I was wearing a wide-brimmed summer hat, and Betty walked up to me and said caustically, “What’s with the fucking hat?” I retorted, “Fuck you, Betty.” She harrumphed and walked away. Her son, Sam Robards, high-fived me. By the end of the evening we were friends again and hugged goodbye.

In the past year, she and I spoke several times on the phone. She was warm and loving, telling me often how proud she was of me, expressing concern over my mom’s health, talking proudly about her kids. She spoke of her infirmities and illnesses, which she called “a fucking pain in the ass,” but didn’t complain in detail or have a lot of self-pity.

We last spoke about a month ago. She called out of the blue just to chat. She asked after my mom, asked what I was working on, and told me how proud of me my dad would be; we said we loved each other. I said I would see her soon.

In late August I went to her small, simple funeral. All her children were united in expressing their belief that their mom “drew the long straw” in how she died: She passed away quickly, within hours of suffering a stroke from which she never regained consciousness. She died knowing her children and grandchildren were all well, loved and happy.

In life, too, she drew the extraordinarily long straw. As Stephen Bogart said, with the same trademark dryness, directness and honesty as his mom, “Hey! She got to be Lauren Bacall. And that’s a pretty great way to go through life.”

Amanda Green is an actor, singer and songwriter who lives in New York City.