Directing is a lonely business. There was the time, long ago, when an actor-manager, also working as a member of the acting company, would take on the role of director. In recent history, and certainly in our current moment, the director is the auteur, an artist trained and expected to have a “vision,” a “concept,” an “approach” to a production. This vision, ideally, springs fully formed from the isolated brain many months before the show is cast.

Having worked exclusively as an actor for so many years, I was accustomed to creating in a room full of people. An actor arrives in the rehearsal room on the first day fully prepared to begin work. The actor’s work is created through the back and forth, give and take, of the rehearsal-room process.

Now I direct plays. And directing (in the institutional model) doesn’t work like that. The timelines are so long that a director needs to have a very clear and clearly articulated approach to a production many, many months before first rehearsals. The scenery and costumes are being built before rehearsals have begun, almost always before the show is cast. The director is asked to answer question after question from designers and producers 10 months before rehearsals begin, and every fiber in the body screams against it. I both understand the necessity of the approach (if one would like the luxury of a set and costumes) and balk at how unreasonable the expectation is. And when I am prepping a production, all those months before rehearsals are to begin, I want so badly to have collaborators. It is, for me at least, a lonely business.

I’ve long struggled with the question of how directors find the opportunity to grow in their craft, when the work we do is so isolated. We may have other directors whose work we love. But what we really love is the result—and we often have little idea how they got there. I have tried in the past to invite colleagues—directors I respect—to look at my work and then constructively reflect back to me what they see: What was successful? What worked less well? And I found that, though I would collect this information and vow to apply those lessons the next time around, the subsequent play would prove to be an entirely different problem, requiring entirely different tools. All the feedback was always coming after the process.

There’s a way out of this conundrum: co-directing. The real joy and professional growth that co-directing engenders derives from the fact that you’re working with a partner from day one—on the text, the design and the rehearsal process of making the play. A co-director is continually interrogating the work all the way through (as opposed to designers, who are deeply involved both early and late in the process, but only intermittently in between), and it is a thrill to be able to work in the same room and share ideas, offer alternative ideas, propose alternative approaches, reflect to one another in real time what is and is not working. The opportunity to be deeply embedded in another director’s process is a tremendous gift.

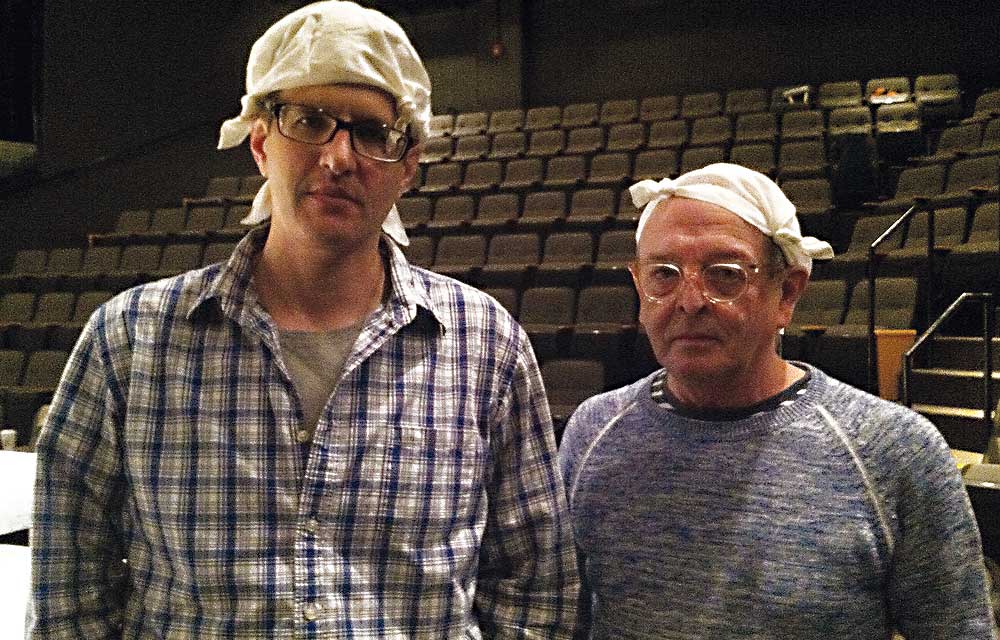

I’ve co-directed three times now, all on large-scale projects and in rotating rep here at PlayMakers Repertory Company in Chapel Hill, N.C.—once with Tom Quaintance on the two parts of Nicholas Nickleby, once with Mike Donahue on Henry IV, Parts I and II and Henry V, and once with Dominique Serrand on The Tempest and Metamorphoses (set in and around a 15-ton pool of water). Those three collaborations are on the short list of my most meaningful directing experiences because of the enormous growth in each of those journeys.

For most actors, one director is more than enough—two seems, well, excessive. And it was very clear on each of these projects, since they were produced at the theatre I lead, that it was incumbent upon me to ensure that the guest director had an equal voice. Tom Quaintance puts it this way: “We had both been around less than completely successful co-directing models, and we were aware of the possible problems surrounding Joe being the artistic director and me being the guest. None of it would have worked without being clear with everyone up front—designers, stage managers, actors, everyone—that this was a co-direction and not an A-director and a B-director. It was the first thing Joe said at the first design meeting, and the first thing he said at day one of rehearsal. It was sincere and entirely necessary.”

Mike Donahue talks about the challenge “of really setting a tone of open collaboration and equal status, so that we wouldn’t be in a fractured room, that the actors could trust in a cohesive process between the two of us, trust that we wouldn’t contradict one another in a counterproductive way, and that we would either always be, or be able to get back on, the same page.”

Dominique Serrand had just opened his Imaginary Invalid here at PlayMakers in a new commission by David Ball when I invited him over for a glass of wine to discuss the idea of our co-directing the following season’s Tempest/Metamorphoses rep together. Every time I mentioned it to colleagues they would look at me worriedly and say, “Are you sure?” or “How’s that going to work?” Serrand describes the invitation this way: “Joe and I met at his request, and he asked me if I would like to co-direct with him. What a bizarre and confusing proposition! I went away and asked myself what I could bring to this inviting table. Once I realized that I could learn from it, and against most of our mutual friends’ advice, I accepted the offer.” I had been through the co-directing process twice before, and I encouraged him to say no if he wasn’t really sure that he wanted to do it—because it can be just about the hardest thing you can try to take on. I was thrilled (and terrified) when he said yes.

I adore Serrand and his work, but of the three collaborators, Dominique and I were farthest from one another in terms of vocabulary and approach. But I also knew that Serrand and I had shared ideas about what passes for good and bad work—we had learned that we admire many of the same artists, that we get angry about many of the same things, that we enjoyed one another’s company a great deal. I thought (very selfishly) that it might be an opportunity for me to vigorously learn and grow stronger as an artist.

And it must be said that I never laughed as much as I did during that hugely challenging process. Serrand, like Quaintance and Donahue, is a deep, profound and generous collaborator, and he worked as hard to develop my ideas as he did his own. He worked hard to protect the theatre’s resources; it was Serrand who suggested that we bring in no outside guest actors but build the production entirely with PlayMakers’ resident acting company.

The key to success in all instances was preparation. For Nickleby, in order to get the 320-plus pages of text staged, Quaintance and I worked in separate rooms much of the time, and we storyboarded Nickleby rather like a film, so that when we knit together the two rooms’ work at the end of the day, the staging and playing were coherent. Quaintance says, “Clearly, in tackling six-plus hours of text we needed to agree on how we were getting from scene to scene. More important, we needed to have a shared sense of what questions each scene presented—we didn’t need to know the answers, but if we were going after competing questions, that would serve no one.”

The Henry cycle worked similarly. There was simply so much text that there would be no way to complete the work in only one rehearsal room.

Donahue talks about not just the challenge of working in two separate rooms some of the time, but also says this: “We each approached a rehearsal room with different styles and rhythms, so the process of figuring out how to leave space for one another, while maintaining the health and productivity of the company at large, was one of the most interesting and challenging things. A big part of this was learning that co-directing didn’t mean needing to, or pretending to, always agree 100 percent of the time—it meant that we had to be committed to the same big-picture ideas, and the company had to trust that that was so.”

In all three instances, my co-directors and I committed to not dividing the scenes based on perceived skill sets—i.e, “You’re good at the little intimate scenes, why don’t you take that, and I’m good at the big crowd scenes, so I’ll work on those.” A real focus was placed on both directors working on all scenes of both plays. And, to the extent possible, after one director had the first “go” at a scene, when we returned to it next, the other director took the lead.