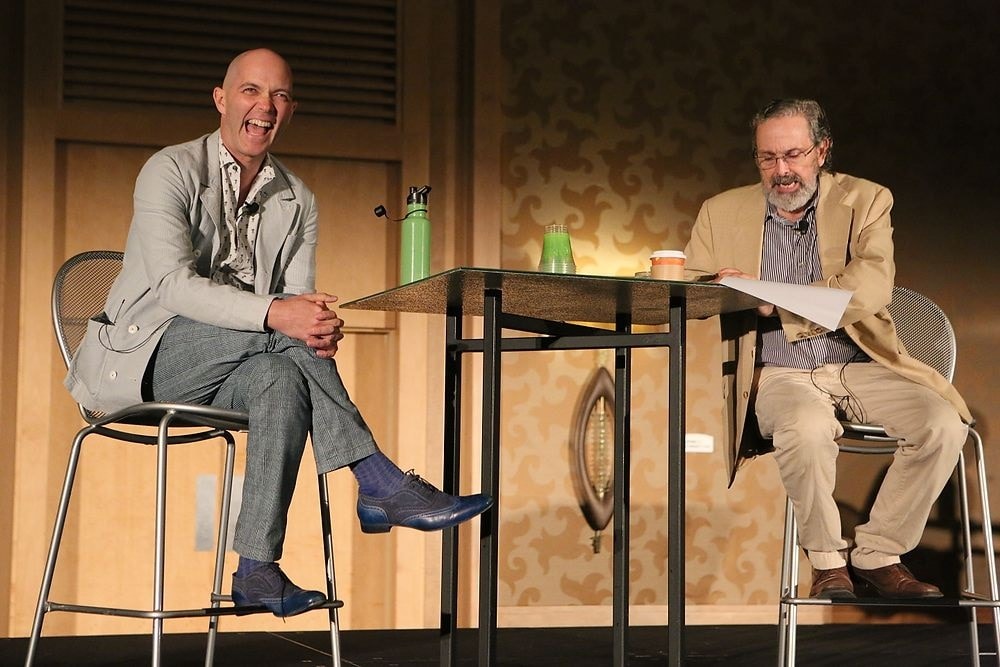

From June 19–21, AT’s parent company, Theatre Communications Group, held its 24th annual national conference, titled “Crossing Borders.” Below is a recap of plenary that consisted of a conversation between Taylor Mac and Craig Lucas on Friday, June 20, 2014.

I go back and forth about labels. You can describe me as a gay political performer, or you could say I’m a poofter princess prancing against the patriarchy. I mean, really—which would you rather see? —Taylor Mac

It’s not as though the 900-plus TCG conferencegoers packed into Friday afternoon’s plenary session—billed as “A Conversation with Taylor Mac and Craig Lucas”—were unacquainted with the classic genre of drag theatre. Cross-dressing and gender disguise are venerable traditions in the long and twisty history of world drama; these days, any American town of a certain size is likely to have a drag-performance venue of some import, and even in those remote territories where men in pearls might be viewed askance, “RuPaul’s Drag Race” makes its counter-case on cable. For some ensembles and companies with an LGBT focus or queer sensibility, drag is simply de rigueur.

But the work of Taylor Mac, it turns out, is another matter. He’s a drag queen, all right, who clearly takes inspiration for his decorative excesses from the 1970s camp era and its cult heroes (downtown NYC filmmaker Jack Smith, Ridiculous auteur Charles Ludlam, San Francisco’s street-savvy Cockettes, the great unsung drag innovator Ethyl Eichelberger), but Mac’s not in it for the usual payoff—gender reversal is not much more than a starting point. As interviewer Caridad Svich put it in American Theatre’s Nov. ’08 cover story on Mac, “He is in pursuit of the radical openness of possibility.” In his performances, gender sheds its binary polarity and becomes a fluid, malleable concept. The effect can be both unsettling and ethereal.

How does he manage it? Behind the drag persona, Mac has heavy artillery at his disposal. He is an accomplished, Meisner-trained actor, as evidenced by the shelf of awards that greeted ingeniously effective performance last season as Shen Te in Brecht’s Good Person of Szechwan. He’s a singer whose vocal talent is showcased in a duet concert show with Mandy Patinkin (scheduled for debut next spring), and he’s at work on a much-anticipated 24-decade pop-song project. He’s a burgeoning playwright, whose Hir packed the house at San Francisco’s Magic Theatre earlier this year and will appear again at Mixed Blood in February. His design sense permeated a national array of productions of his epic melodrama The Lily’s Revenge. He strums a ukulele with aplomb. What can’t he do?

In his loose, congenial, laughter-courting stage conversation with Mac, playwright Craig Lucas touted the full range of his comrade’s theatrical assets. “Taylor is the most protean and visionary, humane and empathetic artist we have,” Lucas declared admiringly, acknowledging Mac’s skills as a “gender toyer-with” and an “egalitarian empathizer.” The pair dove into a discussion of durational work (“The wackiest shit I ever heard of,” Lucas called it), which Mac wryly defended as a theatrical community-builder. “I love durational work because audience members get to know one another,” Mac reasoned, citing incidents in which patrons who hooked up over the four- or five-hour course of his The Lily’s Revenge went on to start a business together or get married.

Finding entrée into the theatre establishment was, perhaps unsurprisingly, tough for Mac. “I couldn’t find my way in—the gatekeeping was so intense. So I went to the clubs instead, where they take anyone!” Those clubs—downtown basement hangouts where sex and performance rub shoulders—were their own kind of education: “I learned a lot in that world—it taught me to be in the moment.” Those lessons have vaulted Mac from basement to glitzy cabarets and music clubs and on, in recent seasons, to Lincoln Center, the Public Theater and American Repertory Theatre, as well as festivals and solo gigs around the world.

Mac is nothing if not quotable—the aphorisms, declarations and bon mots came in a steady stream. On admitting children to his session: “I didn’t want kids here because I wanted an adult afternoon. Our culture caters to children too much, don’t you think?” On audiences: “Your job as an artist is to surprise them every 10 seconds.” On auditioning: “I don’t believe in it.” On what he learned performing in clubs: “If something threatens to take attention away from your story, then you need to incorporate it into the story. So there were lots of blowjobs alongside the ukulele.” On production commitments: “Give me dates for my play. I’ll make it amazing. And if it’s not? Oh, well. Half your plays aren’t amazing anyway!” On what he’d like to see at the “mountaintop”: “A celebration of heterogeneity…I’d like us to stop needing to see ourselves in all our stories and start instead to have a little more curiosity about those who are different.”

After Lucas stirred the plenary crowd with his heartfelt recitation of a gothic/romantic lyric from Lily’s Revenge (“A flower falls much faster than a wish”), Mac responded to a from-the-audience request by conference stalwart Todd London to sing, winning another round of applause for his sweet, clear tenor riff on FDR’s “fear itself” speech.

The session concluded with Magic Theatre producing a.d.. Loretta Greco’s presentation to Mac of TCG’s coveted Peter Zeisler Memorial Award, which recognizes theatrical innovation. “After a decade of trying to be invited to the party, Taylor threw his own,” Greco noted, “creating a body of cabaret and concert work that broke barriers in content and form. I love this man,” she intoned warmly, “and every time he walks into my theatre, he makes me want to be a better artist and a better person.”

No less deeply felt were comments delivered at the start of the plenary by longtime Goodman Theatre executive director Roche Schulfer, who was presented (by his Goodman colleague Steve Scott) with TCG’s Visionary Leadership Award. Recalling his surprise at Schulfer’s “deceptively youthful countenance” at their first meeting 34 years ago—“he appeared to have just come from his high school prom or fraternity pledge week”—Scott testified to Schulfer’s savvy leadership over the subsequent decades. “It can be done,” Schulfer responded, in remarks that stressed the common ground all theatremakers share. Of the Goodman’s enduring vitality he noted, “Transformation can take place.” But Schulfer kept his comments brief because, as he put it, “I’m the only thing standing between you and Taylor Mac.”

Sidebar: When Drag Is the Headline

The conference-wide ripples of excitement about drag performance and its use in the inimitable work of Taylor Mac prompted this reporter to take a look back over American Theatre’s 300-plus issues to see just how often drag artists were featured on the magazine’s cover. Here’s a rundown:

Gazing languidly from May 1988’s cover (in modest black-and-white) is a youthful Harvey Fierstein, gay theatre’s most prolific and enduring hit-maker, decked out in chenille and net stockings for his Torch Song Trilogy’s arrival on Broadway. His visage illustrates an expansive essay by critic Don Shewey, “Gay Theatre Comes of Age.”

Writer/performer John Fleck is fetching in mermaid garb on the cover of Sept. 1990, appearing in his show Blessed Are All the Little Fishes, one of the works that got him into trouble with the U.S. Congress. Fleck is heard from in Paula Span and Carla Hall’s report “At Home with the NEA 4.”

Actress Kelly Maurer takes on Hamlet, a favorite target for cross-gender casting, on March 1992’s cover image of director Eric Hill’s Suzuki-style Hamlet at Massachusetts’s StageWest. The accompanying article, “Hamlet’s Body,” is by scholar Arthur Holmberg.

A month later (April ’92), the late, great Wooster Group actor Ron Vawter, in glittery makeup and jewels, holds the cover as underground hero Jack Smith in a museum-sponsored performance of Roy Cohn/Jack Smith, accompanying reporter Alexis Greene’s article “Off the Walls.”

Recumbent in silk on the cover of July/Aug. 1988 is actor B.D. Wong in a role that brought him international acclaim, Son Liling in David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly. The issue contains the complete text of the play.

Several actors seem prone to gender-swapping in Jan. 2002’s cover image of the New York company of The Donkey Show, director Diane Paulus’s hit riff on Midsummer. The photo goes with Lenora Inez Brown’s Paulus profile, “She Turns the Beat Around.”

The man himself, Taylor Mac, in glittery stars-and-stripes makeup, gets the star treatment on the cover of Nov. 2008, the issue in which Caridad Svich’s insightful interview, “Glamming It Up with Taylor Mac,” introduces him to a larger U.S. public.