Cabaret began in Hal Prince’s apartment. It happened two weeks before John Kander and Fred Ebb’s ill-fated musical Flora the Red Menace opened in New York. The songwriting duo met at the home of their producer, who was itching to start the next project.

“Cabaret was really Hal Prince’s idea,” Kander proclaims. Bookwriter Joe Masteroff elaborates: “We never thought the show would be a big success, because it had a very unhappy ending. And Broadway musicals didn’t have unhappy endings in those days. It was unthinkable,” he says flatly. “When the show first opened in Boston on its tryout, during the first few performances before the reviews came out, people would leave mid-show because they knew the title was Cabaret, and they assumed that it was going to be just that. Once the reviews came out, people stopped leaving, because they knew what to expect—but those first few audiences were very disappointed.”

Well, Prince’s idea turned out to be right on the money, and the show opened to great acclaim on Broadway in 1966. The rest is history, one might be inclined to say, but that observation would prove premature.

Flash forward almost 30 years, and enter Sam Mendes, a little-known British director staging what had by then become a Kander-Ebb classic at London’s Donmar Warehouse. That production, celebrated for wrapping its audience in a dance-club ambience with the actors also serving as the band, would go on to New York, making Mendes and his Broadway collaborator Rob Marshall two of the most in-demand directors in the business, and turning the show’s Emcee, Alan Cumming, into a household name. While changing the fate of its creators, that particular production of Cabaret also changed the face of New York theatre—two notorious faces in particular, thanks to the show’s required environment.

So, in honor of yet another return of Cabaret—which opened on Broadway this past April in the same production, starring Cumming and helmed by Mendes and Marshall—American Theatre talked to Roundabout artistic director Todd Haimes and members of the original team to get a behind-the-scenes, timeline-annotated look at the little show that could.

Dec. 2, 1993: A revival of Cabaret starts performances in the West End.

“I had heard talk from people that there was a very good production of Cabaret in London, and I packed up and went to the Donmar Warehouse,” remembers Masteroff. “Sam Mendes was not around that night, but he called me the next morning and said, ‘What did you think of the show?’ And I said, ‘I loved it.’ And he said, ‘Let’s have lunch tomorrow.’”

At the time, Masteroff’s She Loves Me, with a score by Jerry Bock and lyrics by Sheldon Harnick, was running on Broadway, the first musical Roundabout had ever produced on the Great White Way. “I came back to New York, and I told Todd Haimes that he’s got to do this show. And that was the beginning.”

“I kept on saying to Joe, ‘Yeah, yeah, sure,’ because I was focused on She Loves Me, not on Cabaret,” Haimes recalls. “But he kept on hounding me about it, and somehow they got me a tape of the production. And even on video, I could tell it was something really extraordinary.”

Mendes, then an unknown stateside, called up Haimes and asked him if he was interested in transferring the production. Haimes agreed immediately, despite being skeptical of Mendes’s two requirements: a) The show needed to be staged in a 500-seat cabaret space, and b) Alan Cumming needed to come to America to reprise his performance as the Emcee.

“How the fuck are we going to do that?” Haimes remembers of his initial reaction to Mendes’s stipulations. “I just wanted the show. No commercial producer would do it, because a 500-seat space makes no sense for a commercial musical. Alan Cumming was completely unknown, and he didn’t have a green card. At the time we weren’t allowed to hire people without a green card.”

July 1996: Todd Haimes announces Cabaret for the 1996–97 season at the Supper Club.

“Looking for a cabaret space proved to be unbelievably difficult,” Haimes says of the almost-three-year quest. “We looked everywhere. It became an obsession of mine.” Roundabout finally made a deal with the Supper Club on 47th Street, now the Edison Ballroom, and announced the production, with Cumming starring and Mendes at the helm. “We actually had a handshake agreement with them—in theatre, a handshake is a deal because contracts are often not done until the show’s half over,” Haimes explains. “However, I learned the hard way that in real estate, until you have a contract, you don’t have a deal.”

And Haimes’s “deal” fell through about eight weeks before rehearsals were set to start. “The Supper Club people basically said, ‘We got a better offer, fuck you.’ They just backed out of the deal, and Cabaret was cancelled,” Haimes says. “At that point, I think Sam believed it was cancelled forever and went on to do his thing, which was getting more and more famous in London.”

Enter Rob Marshall. Haimes called up the American director—who had done the musical staging for Roundabout’s She Loves Me and was eager to start making a name for himself as a director—and asked him if he wanted to direct Cabaret in Mendes’s absence. He said yes. Cabaret would mark his Broadway debut as a director.

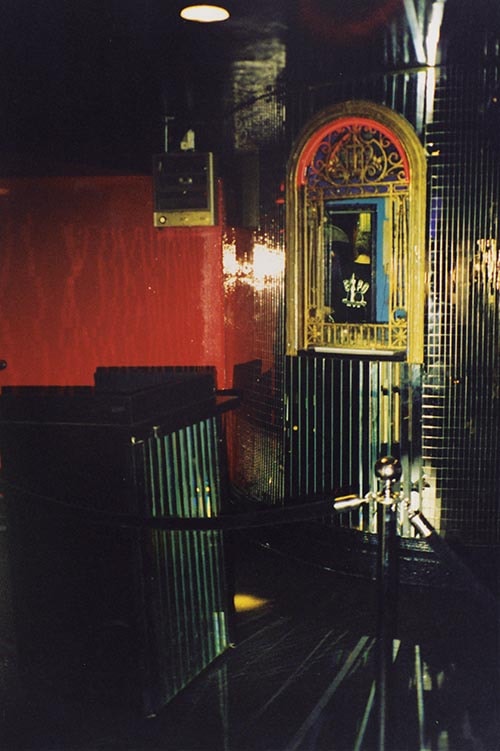

Now all they needed was a space. A Roundabout board member, Douglas Durst, owned the building that housed the former Henry Miller’s Theatre, a bonafide Broadway house that had gone dormant in 1969. “He had leased it out to an outfit called Club Expo, so he suggested that we speak to them about maybe combining forces in some way,” Haimes remembers. “We came to a deal with them where we would do our show every night, and then after the show—believe it or not!—it was converted back into a disco.” The venue had spent its post-’69 days as a porn cinema, then a discotheque called Xenon, then Club Expo. “The Miller’s people had forgotten there was even a theatre there,” Masteroff quips.

So Cabaret was on again—and with a space secured, Mendes was able to make the new dates work and was back on board as director. “I suggested Sam consider Rob as his associate, so they came up with the concept of them being co-directors and Rob being the choreographer,” Haimes says.

“Rob’s middle name is Broadway,” Masteroff jokes. “Doing a show in New York is a lot different than in London. The musical and dancing demands are much higher. Rob brought all of that into it.”

But would it be a Broadway show? Though the Miller’s Theatre once held Broadway status, the venue had lost its Tony eligibility long before. “There was a real concern that some of [the Tony administration committee] felt it shouldn’t be a Broadway theatre,” Haimes says. The minimum requirements were that the space have 500 seats and be in the theatre district. “We had no right to just make the space a Broadway theatre that hadn’t been one for I don’t know how many years. So I had to appear before the Tony committee and beg them.”

March 19, 1998: Cabaret opens at the Kit Kat Klub on 43rd Street.

That’s right, the Kit Kat Klub. Club Expo filed a DBA to officially change the club’s name to that of the musical’s fictional venue. “I did love the fact that it was a working club in the evening,” says Cumming, adding that it was his favorite place to perform the show. “I loved the fact that I could go up to my dressing room and come down an hour later and dance on the very stage that I just performed on! It was almost as though it was made for the production, because we were trying to be down and dirty and authentic and gritty, and this was actually the equivalent of that in the present time. So I was all for it.”

However, while the site-specific feel of the production felt apropos, the relationship with the club owners was less than ideal. “It was a nightmare,” remembers Sydney Beers, who worked with Roundabout’s then general manager Ellen Richard while the show was at the Kit Kat Klub. (Beers later became the company’s general manager, a position she holds today.) “It was a real seedy club. One Tuesday we came in, and all of someone’s costumes were completely missing, and we had a show in two hours. It was insane.”

Haimes concurs. “I would get performance reports on the show every morning, along with info on anything that happened at Club Expo,” he recalls. “One morning I got a report saying, ‘Naked trapeze artist fell off trapeze, is in intensive care at some hospital.’ We had nothing to do with the naked trapeze artist, but that’s the kind of things they had going at Club Expo. I fled every night after the show.”

That June, Cabaret swept the musical Tonys, winning best revival, best actor for Cumming and best actress for its Sally Bowles, Natasha Richardson. It was the hottest ticket in town, but the math didn’t work. “We had this odd situation where the show was a huge hit, but we were only in a 500-seat theatre,” Haimes explains. “We couldn’t pay the actors enough to keep them and have enough seats to be able to afford that.”

July 21, 1998: A construction crane falls on 43rd Street.

The Condé Nast building, 4 Times Square, was under construction, and on that morning, a crane fell onto a building across the street, killing one person and causing the block to close (and as a result, Cabaret). “I’d actually gone to London for a secret trip on the Sunday before it happened, and I came back on the Tuesday and I was trying to get to the theatre,” Cumming recalls. “I was very panicky about getting there on time and all the streets were closed and I was freaking out and then I just realized what had happened.”

“It was a nightmare, because we had the biggest success we’d ever had, and then this freak accident closed one Broadway theatre—which was ours,” Haimes says. “We thought, ‘This is it. Cabaret is dead.’”

A week later, it was announced that the Kit Kat Klub would be closed indefinitely. Roundabout was losing thousands per week with the show closed, and Haimes needed to quickly come up with a plan B. “We were desperate,” he says. Luckily, another disco came to the rescue. Durst knew the owners of Studio 54, and at that moment they had no tenant. “Studio 54 had not been a legitimate theatre for many years. It was a disco,” Haimes says. “And we approached them and said, ‘Would you be interested in us moving Cabaret there?’” They were, if the venue could operate the concessions.

Aug. 20, 1998: Performances resume at the Kit Kat Klub.

“Indefinitely” turned out to amount to only 35 performances, and the cast was able to move back into the theatre temporarily, with one major loss: Natasha Richardson was not able to play her final performance because the closure overlapped with her departure. Jennifer Jason Leigh stepped in as the new Sally.

But the Studio 54 deal was inked, and Beers was in charge of orchestrating the move. While Cabaret was still performing at the Kit Kat Klub, she and a technical director (who later became her husband) oversaw a complete remodeling of Studio 54 and the reconstruction of the show’s set—on a budget. “I had heard the Imperial Theatre was getting rid of its seats, and now we needed seating in the mezzanine,” Beers says, as the capacity increased to 950 at Studio 54. “I went over to the Imperial and said, ‘May I please have your seats?’ These guys looked at me like I was crazy. I brought them over and covered them in leopard print. I mean, it was probably the best theatre grad school program anyone could every sign up for.”

Nov. 8, 1998: Cabaret plays its last performance at the Kit Kat Klub.

The Kit Kat Klub owners were not happy that Cabaret was leaving—they had changed their name, after all, and had no use for a Broadway theatre. But the problems that arose during Cabaret’s tenure—broken glass on the stage, missing costumes, the club owners sneaking friends in for free—led to an attitude of “good riddance” on Roundabout’s part. “It was an acrimonious parting,” Haimes admits. “It was not a happy experience for them or us.” Indeed, the Kit Kat Klub didn’t last long after Cabaret’s departure, though the space remained a Broadway theatre.

The move uptown cost the company $1.5 million, which was a large portion of the company’s then $18-million annual budget. “One weekend we got together the whole cast and teched the show in the new theatre, and started performances five days later at Studio 54,” Haimes says. “Had that not happened, Cabaret would have closed, because it couldn’t have existed in a 500-seat space financially.”

With Cabaret running, Haimes’s gamble paid off, and the show became not only a hit but a profitable one. That profit allowed the company to officially purchase Studio 54 in the summer of 2003, with help from the city, for a ticket price of $22.5 million.

The show ran for six years, closing on Jan. 4, 2004.

Sept. 15, 2010: The Stephen Sondheim Theatre opens its doors.

With Durst as the developer and the Roundabout back as a long-term tenant, the former Miller’s Theatre took on its new name: the Stephen Sondheim Theatre. “In my desperation to do this production, I saved two Broadway theatres,” Haimes reflects. “Both are now permanent Broadway houses, and, coincidentally, we run both of them.”

Flash forward again, nearly four years, to the high-visibility opening on April 24, 2014, of Cabaret, again at Studio 54. Roundabout has brought back the same production, this time with Michelle Williams as Sally—and though the theatre has taken criticism for remounting the Mendes-Marshall version, and for its high ticket prices, there’s a certain 94-year-old playwright who’s over the moon to still be living his dream.

“Ever since I was an infant, I wanted to be a playwright on Broadway. That was all I ever wanted to be,” Masteroff confesses. “The minute Cabaret succeeded, I just retired. I’m not the kind of person who might win a million dollars and couldn’t wait to win another. I know when my dream comes true.”