Erickson was invited to more meetings—with the City’s Grants for the Arts and Arts Commission, and the Northern California Community Loan Fund, a major regional lender and technical assistance provider targeting the neediest communities, which had been hired by Grants for the Arts to connect nonprofits with spaces (it was an NCCLF consultant who helped TBA relocate to its current rental on mid-Market).

Erickson says the city and its allies wanted to use the arts—the performing arts, in particular—to establish a beachhead and transform the neighborhood. Why? “Because we were the bravest foot soldiers around. If you couldn’t get bars to go in, and you couldn’t get restaurants, send the artists in, because they’ll go where no one else will,” he recalls with a laugh. “So theatre was really at the center. I was amazed that the mayor’s office was actively talking and worrying about where companies like PianoFight were going to find a home—that they even knew what PianoFight was!”

Amy Cohen, director of neighborhood development for OEWD and one of the mayor’s more prominent liaisons with the arts community, says her office first approached arts leaders against the backdrop of a “huge vacancy problem” in mid-Market: “We had vacant lots and vacant buildings. So we started working with the arts community to figure out who’s looking to expand.” Early on, Cohen met with Perloff and learned ACT was being priced out of their rental property at 30 Grant Avenue, in the congested shopping district just east of the corridor. ACT wanted to consolidate its conservatory and administrative offices in a building that would also house a second theatre.

“Now we had some square-footage need and an organization that might actually be able to raise money,” Cohen explains by phone. “[We’d been working] in concert with the Arts Commission and Grants for the Arts, which are other city agencies who do arts work. We all knew—it’s not just a matter of figuring out who’s looking for space, but who can afford a building. That’s been the challenge. ACT is in the unique position of being able to afford more than your average performing arts organization, and they still have a bunch of money to raise.”

ACT was lucky to buy when it did. Since then, the dynamic in mid-Market has changed dramatically, thanks to the city’s success in wooing the area’s tech firms into the neighborhood with a payroll-tax break unveiled in 2011. When tech started moving in, theatre and performing arts found themselves in a newly reshuffled deck of players, says Erickson, as real estate prices in this heretofore low-rent area began to climb steeply.

“The Twitter deal happened, and things changed amazingly fast,” recalls Erickson. “If what you wanted to do was to fill up empty spaces and raise commercial rates, it’s been hugely successful at that,” he laughs. “But here’s the problem now: Is there room for the arts nonprofits in general, theatre in particular? The vision of what Central Market could be is becoming a bit of a victim of its own success.”

The aforementioned PianoFight, a small company devoted to new plays and comedy, also got into mid-Market just before the real estate market took off. It secured a 10-year lease, bank loans, investors and private and public contributions (including a $75,000 development grant from OEWD) to acquire and renovate a legendary Tenderloin establishment, Original Joe’s, at 144 Taylor Street—a sketchy skip-and-a-jump north of Market Street. The two-stage, 5,000-square-foot complex, due to open in 2014, sports a restaurant and bar.

And PianoFight is not alone. Rob Ready (who co-founded the company in 2007 with Dan Williams and Kevin Fink) ticks off the performance stages old and new on the surrounding two blocks. “In a two-block radius you’re looking at 10 venues [including commercial establishments as well as nonprofit theatres and arts organizations] and about 20 different stages by 2015 or 2016. To my knowledge, there’s no other area of the city that can say that.”

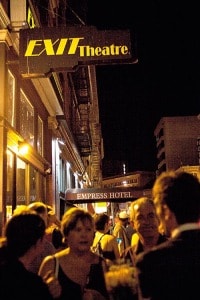

Richard Livingston, co-founder with Christina Augello of the EXIT Theatre, one of the venues in Ready’s tally and active in the Tenderloin for 31 years, stresses that this surge of arts development, while significant, merely extends a much longer renaissance.

“If you go back 40 years to the early ’70s, starting at 3rd Street [and Market], there was no museum row…no Yerba Buena [Center for the Arts], the Warfield was closed, the Golden Gate was dark, the Orpheum was dark, there was no Davies Symphony Hall, there was no SFJAZZ Center, there was no ballet. If you add that up, you have over 10,000 seats. We’ve created a Lincoln Center in the last 40 years. At the same time,” Livingston continues, “there was no EXIT Theatre, Bindlestiff, Cutting Ball, Boxcar, Phoenix Theatre, Luggage Store Gallery—so we’ve also created an East Village in the same location. That’s unique in the United States.”

Livingston also points to the real and potential symbiosis between storefront theatres like the Exit and the plethora of nonprofit agencies in the Tenderloin that own such buildings. “What is overlooked in all of this is the idea of having small performing arts in commercial retail spaces in nonprofit-affordable housing buildings. We’re an example of it,” he notes. “The basic agreement is that we’ll take total responsibility for the build-out, which we do with our sweat equity; we’ll take responsibility for the maintenance; and we will provide positive nighttime activity, which is something these organizations have not been able to do in locations like this,” he says. “In return, we get long-term, low-cost rentals in a building that’s not owned by a speculator.”

Such an arrangement, he argues, is an underappreciated option for smaller arts organizations in need of space. “I think it’s a model that really should be explored and pushed.”