Jerry Manning died the day before May Day. He’d appreciate this fact. I’d like nothing better than to sidle over to the Seattle Rep stage door, where he would perch himself for smoke breaks, and point this out to him. I can imagine him staring at me, listening with his watery blue eyes fixed on my mouth as I let him know he was dead, and then, his hand trembling only slightly, he’d emit a single, genuine, barking laugh. Then he would insouciantly snap back something like, “Well…it serves me right. Now everyone on the board will think they know I’m a commie!”

But a better line than that, I’m sure. I’m sad we can’t know, because I am just the poor wretch writing this, and Jerry isn’t here anymore.

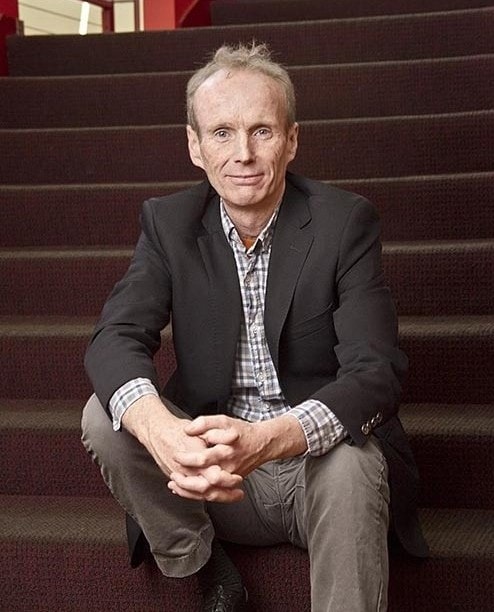

Jerry Manning was the rarest animal in the American theatre: He was an artistic director of a flagship of the American theatre system who not only believed but lived his belief every day. He was the greatest artistic director Seattle Repertory Theatre has had in memory, and it was because he actually believed in the local artists he filled his space with. Part of his charm was that he was genuinely self-effacing, a rare quality in directors and a vanishingly rare one in artistic directors.

A lot of that was due to the fact that he’d come to the Rep years earlier as associate artistic director. I first met him in New York well over a decade ago after a colleague connected us. I had just finished my first major Off-Broadway run, and I was still wet behind the ears and hungry to make a life in the theatre. We met in Father Nemo Park down in the Village on a day in the early spring when snow still covered the ground. We sat on a bench together, and Jerry was blunt. “Let’s just be clear, Michael. I can’t help you. Hell, I can’t even help myself!” Then that sardonic laugh, and he smoked, and we started really talking.

The fact that he felt trapped in his life was a curse he turned into a blessing, because in the years that followed, Jerry turned more and more to the local theatres in Seattle to find true creative outlets. He directed in local garage theatres and grew to see and trust the strength of the artists in Seattle at a time when the Rep and all the major players believed almost exclusively in the cult of NYC and L.A.

During a difficult leadership transition at Seattle Rep in 2008, Jerry suddenly found himself the interim artistic director. In a situation where many would have played it safe, he made brave choices about finally opening the Rep’s doors to local talent after decades of neglect. He was a fantastic revolutionary because he was egoless—he just wanted to do right by people, and with those people create art that moved all of us.

The best decision the board of directors at Seattle Rep have ever made was to finally make Jerry’s appointment permanent, which they did in 2009. By throwing away the broken system that most of the American theatre uses—where boards are dazzled by Tonys and flashy work from freelance directors—Seattle received the great blessing of a leader who actually knew the community and cared deeply about its artistic ecosystem. These past few years have been a golden age in Seattle theatre, and this quiet revolution has all been because of Jerry’s quiet choices.

He was my friend, and I miss him terribly. He was often the best kind of optimist—which is to say he was prone to dark brooding and worry, and like so many of us he worried about the state of the theatre. I wish I had told him what I believe—that if the American theatre is to survive in a way that matters, there will be so many more leaders like him in its future.

To everyone, from shop hands to audience members to myself, he was simply Jerry—one word. He led with a light touch and deep respect, and he was humble before the work. He would think everything I have written here was too much, but he would also secretly love it. I wish more than anything I could walk down to that door at the side of the building and talk to him about it. I want to hear him laugh.

Mike Daisey is a monologist, author and working artist.