In commemoration of the 50th anniversary year of the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Conn.,The O’Neill: The Transformation of Modern American Theater, an illustrated history of the influential theatre organization, written by playwright and theatre historian Jeffrey Sweet, will be published in May by Yale University Press. This excerpt from the early sections of the book recounts the O’Neill’s beginnings and its stormy first summer session.

Though best known for the National Playwrights Conference, the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center has pioneered programs in puppetry, musical theatre, cabaret, international exchanges, media and criticism, as well as founding the National Theatre of the Deaf and the National Theater Institute. Each of these initiatives in turn has had a ripple effect. Indeed, much of what we now take for granted in contemporary theatre contains DNA that can be traced back to a green patch of land 125 miles from the streets of Greenwich Village, overlooking Long Island Sound in Waterford, Conn.

It began with the 26-year-old George C. White and his wife Betsy sailing in the Sound with George’s father. Betsy remembers, “His father said, ‘See that mansion up there? Remember the Hammonds used to live there?’” He pointed to a large, dilapidated structure at the top of a hill. Betsy remembers her father-in-law explaining, “The Hammonds had given the property to the town of Waterford. The town was really only interested in the beach. They didn’t know what to do with the rest of it. A lot of kids thought it was a good place to hang out and smoke pot.” White asked his father whether the town had any particular plans for the house and the other buildings on the property (including a barn). The leading idea? To set them on fire to give practical experience to the local fire department.

White, a native of Waterford, thought there had to be a better use for the place. American playwriting icon Eugene O’Neill had spent much of his young life in the area. O’Neill biographers Arthur and Barbara Gelb devote several paragraphs in their book, O’Neill: Life with Monte Cristo, to the young O’Neill romancing girlfriend Barbara Ashe on the very property White sailed past, mentioning that the long-gone railroad millionaire who owned it—Edward Crowninshield Hammond—had had them chased off the grounds.

White was a recent graduate of the Yale School of Drama, and it occurred to him that a link between the legacy of O’Neill and one of America’s leading drama schools would be a natural. He proposed that the site be used as a summer adjunct of the school. The Yale Corporation, however, refused to approve the idea.

White had to adjust his goals. In the meantime, in 1963, along with others in Waterford interested in the theatre, he did the paperwork to incorporate an organization called the Waterford Foundation for the Performing Arts as a not-for-profit. The foundation negotiated a 30-year lease at one dollar a year for the area of the park on which the buildings stood and started to raise money to begin operation, as well as figure out what that operation should be.

Initially the idea was to open a new theatre. But the funding wasn’t available to do that. “It was probably a blessing,” White comments. “The obvious thing, if we had a lot of money, would be to try to do an O’Neill play. But we didn’t, so we had to come up with something that would get us started.”

A young playwright, Marc Smith, approached White as he was trying to define a direction for his new organization. White remembers, “He said, ‘Why don’t you have a playwrights conference?’ And the reason that that sounded good to me was it was cheap.” So White decided he would invite playwrights to Waterford. But how to find the playwrights?

He recruited initial participants primarily from two organizations. One was New Dramatists. The other organization brought White into contact with Edward Albee. Albee and Richard Barr and Clinton Wilder (the co-producers of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?) had channeled some of the profits from their hit into the Barr-Wilder-Albee Playwrights Unit, a group the three of them had founded in 1961. Drawing on people affiliated with these groups, as well as some White knew from his connections with the Yale School of Drama, the Waterford Foundation invited 20 writers to attempt a realization of Smith’s conference concept. White also turned David Hays, who had designed the two landmark productions that in 1956 sparked a revival of interest in O’Neill, The Iceman Cometh Off-Broadway and the American premiere on Broadway of Long Day’s Journey into Night. Both had been directed by José Quintero.

In the meantime, the foundation had been blessed with a psychological boost. In a letter dated Aug. 3, 1964, Eugene O’Neill’s widow, Carlotta, wrote, “This is to tell you that I am delighted that you wish to name your foundation for a theatre project in the name of Eugene O’Neill; could he know this, he would be more than pleased.” She ended by writing, “May you have even greater success than you expect.” Her wish would come to pass beyond anyone’s expectations.

The foundation was renamed the Eugene O’Neill Memorial Theater Foundation on Nov. 19, 1964, and received its tax-exempt status on Nov. 23. And on Aug. 4, 1965, “the O’Neill” welcomed 20 playwrights to the grounds at Waterford for the birth of the National Playwrights Conference.

It was not an easy birth.

The first John Guare heard of the inaugural National Playwrights Conference was in a 1965 letter from White. “Would I be interested in coming to Waterford, Conn., to discuss the beginning of a new possible theatre?” The idea appealed; Guare had yet to find a way to establish himself in the theatre scene that existed. “The abyss between Broadway and Off Broadway and then between Off Broadway and Off-Off Broadway was immense.” He remembers that there was the beginning of a sense of community among the young writers in New York, particularly the significant number of them based in Greenwich Village. “We were all living. Just hanging out. And feeling that downtown was a different world. I lived in a fourth-floor walk-up with a 20-foot ceiling and a skylight and a wood-burning fireplace and an eat-in kitchen and a bathroom that looked down on a garden. Thirty-two dollars a month.

“Terrence McNally lived over here and Lanford Wilson lived over there. It was being young and fun and fucking around. You’d go to the theatre every weekend. You’d go to La MaMa and Theatre Genesis and Cino and Barr-Wilder. You didn’t go to see something specific, you went to see what was there.”

As the first day of the conference approached, invitee Frank Gagliano got a call from White. “George would rent a station wagon for me if I could bring up some playwrights who didn’t drive. I think Sam Shepard might’ve been in the car, but I know that Lanford Wilson was.”

Most of the others invited, Guare remembers, boarded a bus that left from Times Square “to take us Fresh Air Fund kids to the country.” The “Fresh Air Fund” reference suggests a theme Guare often refers to about the attitude then toward helping young writers. “That new playwrights were sort of like a disease. Charity. Polio was taken, you know.”

And so the playwrights arrived in Waterford. Among the others in that first cohort were Charles Frink, John Glennon, Israel Horovitz, Joe Julian, Tobi Louis, Leonard Melfi, Joel Oliansky, Tom Oliver, Sally Ordway, Emanuel Peluso, Doris Schwerin, Sam Shepard, Douglas Taylor, and the writer who suggested the conference in the first place, Marc Smith. Lucy Rosenthal recalls, “They housed us that first year with townspeople, and the houses were quite grand, or so I thought then.” Their lodgings arranged, the writers began to look warily at what was being offered by a host many of them had never met.

Playwright Lewis John Carlino, who arrived at the conference late, wrote about his apprehensions in the Sept. 12, 1965, New York Times. “What’s to be gained by such a meeting?” he thought as he approached Waterford. “What can possibly be exchanged between me, us, and the panelists (top people in the fields of design, directing, producing, acting, agenting and writing) that hasn’t already been discussed endlessly before and shaped into all the neat, seemingly significant and wholly inane generalities usually found in Sunday supplements entitled, ‘What’s Wrong with the American Theater?’ I don’t know about these other guys, but I’ve got misgivings.”

The playwrights entered the drive of the Hammond Estate, a dozen acres sloping up a broad lawn from the Long Island Sound to the 24-room mansion White’s father had pointed out. The mansion cut a noble figure, but it was run down to the point of being dangerous. The nearby barn was in better shape; at least the roof wasn’t likely to collapse. Given the condition of the buildings, White thought it best to hold many of the gatherings in a sunken garden to the east of the mansion, underneath a huge, old, copper beech tree.

Poet Odell Shepard offered the opening remarks of the conference, telling of a time in colonial days when townspeople raced down to the waterfront of New London to catch a view of a caged lion on display on an anchored ship. He suggested this might have been the area’s first example of an entertainment attraction.

Later in the conference, the playwrights heard from Audrey Wood, a literary agent famous for spotting and encouraging playwriting talent. The story of how she discovered and sustained Tennessee Williams through hard times until his breakthrough was legend. She had also had an active hand in advancing the fortunes of Robert Anderson, William Inge, Arthur Kopit, Carson McCullers, Murray Schisgal and Guare, among many other writers. A brochure published by the O’Neill Center in the wake of the conference quotes some of her remarks, including her concern about the effect of the commercial marketplace on contemporary playwriting. “Plays with film potential get the best production breaks,” she is reported to have said. “Nine out of ten serious scripts are brushed aside in favor of comedies.”

As the conference got underway, White became aware of rumbling among the writers. They were angry, particularly the unproduced (and underproduced) ones. “I was totally horrified at all these crazies that came up,” he recalls. Guare believes that some of the anger had its roots in the suspicion that the conference assumed that the writers wanted careers on Broadway. It was an assumption that he also encountered later, when he became a member of New Dramatists. “People would come to New Dramatists, like in 1968, to tell us how to write a hit Broadway comedy. You got the sense that the old status theatre was trying to hold on desperately by its fingernails. It was [also] in the air at the O’Neill. So when we had a chance to speak, we said, ‘We don’t want to be part of this.’ We were interested in the new theatre.”

This anger bubbled up even during what White had assumed would be an uncontroversial panel. “I thought, who’s going to get angry at scenery?” So he scheduled as one of the early sessions a conversation featuring set designer David Hays and costume designer Patricia Zipprodt. But the dialogue soon moved to confrontation. Frank Gagliano says, “I guess it must have been David Hays who said something about never reading stage directions. Just reading the script. I remember seeing red at that. Not reading a writer’s stage directions!”

Hays’s version of that encounter is a little more complicated. “I said, ‘Many designers—and I sometimes found myself in this position—want to just read the play, see what they come up with in their mind, and maybe, then maybe, read the playwright’s directions.’ So Sam [Shepard] blew up, said, ‘When I want such and such a set, and when I want such and such a costume, that’s what I want!’ Pat Zipprodt spoke up and said, ‘You know, Sam, if you say that the heroine is in a black dress and she looks like shit in a black dress, I’m not going to put her in a black dress.’ And then I said, ‘I just designed All the Way Home for Arthur Penn. The playwright [Tad Mosel] suggested six settings, and I said you can do it in one without a turntable, nothing. No change. Look at what you save in construction.’” (Hays was nominated for the 1961 Tony Award for the design.)

A meeting with some established producers—Lyn Austin, David Black, T. Edward Hambleton and Judy Rutherford Marechal—also triggered resentment. Carlino’s account confirms Guare’s theory: “Mr. Black suggests we write comedy for our first Broadway effort. Then the next plays can be serious. From the back of the barn comes a sharp retort, ‘Nuts!’”

More confrontations came during a panel on criticism, which featured, among others, Boston eminence Elliot Norton. Says Gagliano, “I seem to remember Eliot Norton bringing up Shakespeare and Sam Shepard getting up and saying, ‘Fuck Shakespeare! It’s not about him anymore!’” Shepard left Waterford midway through the conference. White shrugs at the memory. “Lanford tried to get him to stay. But we served a great purpose for Sam: He needed some place to walk out of. I mean he really did. To make a statement. He was 19.”

According to White, what rescued that first conference were two playwrights, one living and one dead. The living one was Edward Albee. White arranged for Albee and one of his producing partners, Richard Barr, to meet with the young writers. Albee had a unique status. On the one hand, he was a famously uncompromising figure in the playwriting world whom the invited writers saw as a colleague and ally. (As Carlino wrote, “I mean, he’s one of us. He understands.”) On the other hand, he was commercially successful, having authored Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the most notable new play of the past decade.

Without particularly intending it, Albee found himself bridging the gap between the would-be insurgents and what they perceived as the establishment. Not exactly famous in those days for being a peacemaker, Albee nonetheless kept stressing to his fellow playwrights that the O’Neill organization was worth taking a chance on. Albee explains his support of White was based on a simple fact: “If nobody’s giving you anything, and then somebody decides to give you something useful, you’re enthusiastic.”

White says, “I told him, ‘I owe you a lot.’ He really helped make order out of chaos.”

Albee’s support for the O’Neill is all the more notable because it ultimately evolved into a place with a method that he does not find personally useful. Albee famously composes his plays in his head, puts them on paper in a rush when he feels they are ready, goes into production, and doesn’t revise much. He doesn’t hesitate to state that the idea of staged readings and workshops of his own work holds no appeal for him, but acknowledges they may be of value to those who don’t write the way he does. With characteristic mischief, he says, “I tell playwrights: ‘Don’t write first drafts. Write the finished piece.’”

As for the dead playwright who eased the tensions—that was Eugene O’Neill himself.

José Quintero arrived in Waterford with actors Barbara Colby and Terry Kaiser and gathered the conference participants for a presentation in the barn. As White wrote, “It was necessary to surround the [barn] with fire engines, as there was still dry hay beneath the floor (which sagged in the middle). The lighting was provided by a line of 75-watt bulbs strung down the center. The audience sat in folding chairs provided by the local firehouse.”

The presentation was of a rehearsed reading of a scene from A Moon for the Misbegotten, featuring the character of Jamie Tyrone, the alcoholic older brother familiar to audiences from Long Day’s Journey. Moon focuses on the relationship between Jamie and Josie Hogan, a young woman who lives with her father on a farm Jamie has inherited. Josie is described by O’Neill as being “so oversized for a woman that she is almost a freak.” In one of the most poignant encounters in dramatic literature, one night Josie expresses her feelings for him. But it is too late for Jamie to be redeemed. Eaten up with self-disgust and guilt, he now wants nothing more than to greet permanent oblivion.

When he wakes, he remembers little of the evening before and affects a jauntiness before leaving her for what she knows will be the last time.

The conference participants watched Quintero and his actors explore this extraordinary material, aware that O’Neill pictured the location of the Hogan farm near the Harkness Pond, a stone’s throw from where they were sitting.

Gagliano remembers, “The woman playing Josie wasn’t a big girl. She said, ‘How do you act big?’ And Quintero said, ‘By acting small. A big person wants to be small, like a drunken person wants to look sober.’ And she did it and it worked.” Carlino was struck by “the rapt faces caught by the crazy magic of the creative process.”

The balm Josie offers Jamie reportedly conferred a kind of balm on the contentious playwrights at Waterford. White sensed that the anger that had simmered throughout the conference had dissipated. The warmth of Josie’s pure love brought the first conference to a close as if it were a benediction. White wrote, “It was an eloquent expression of talent, theatre and O’Neill, and served to bond the conference together; it changed the negative attitudes into an overall feeling of enthusiasm and optimism.”

The playwrights returned home. Carlino described his thoughts as he drove back. “A whole town said, ‘We feel the future of the theatre rests in the hands of the playwright and we want to do something about it.’ Okay. So they open their homes to a bunch of strangers. . . . And guess what? They want us back. And they are going to spend the next year trying to get the money to bring us…Nothing like this has ever been done before with us or for us.”

Guare was more skeptical. “I thought I would never hear from them again,” he says of the conference organizers.

Jeffrey Sweet is an award-winning playwright. An exhibition on the history of the O’Neill opens May 17 at the New York Public Library.

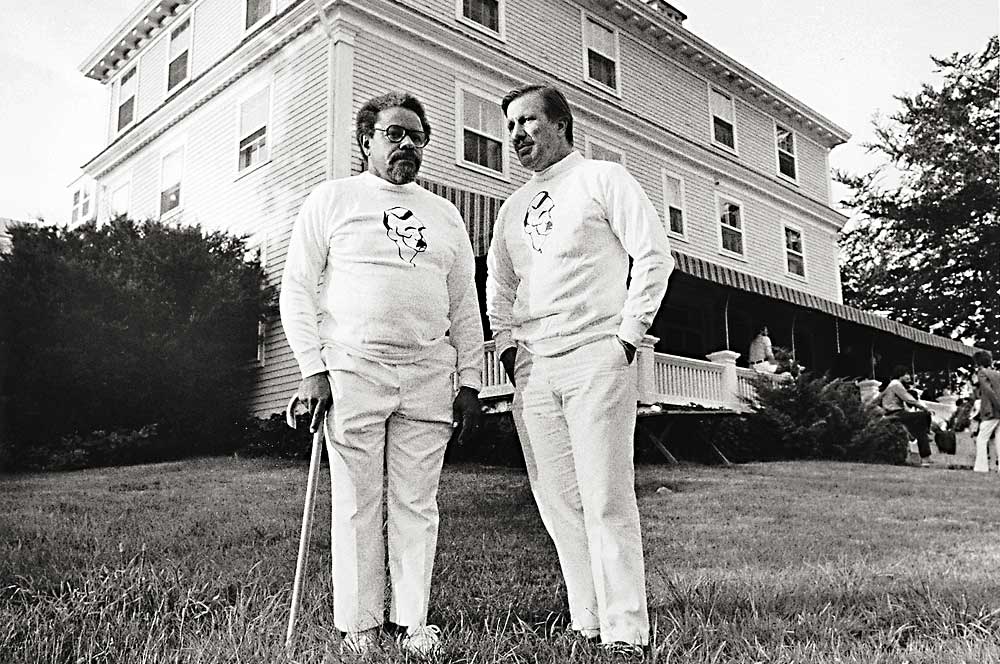

Photo Credit: George C. White in 1965 (Photo courtesy of the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center)