From the start, Simpson set out to create a theatre that reflected the values of those who had influenced him: inexpensive ticket prices (Klein), minimalist staging (Grotowski), new American work (Richards). The first play at the Flea was Bedfellows, by Herman Farrell Jr., the son of a prominent New York City politician. It was a play about the inner workings of New York City politics.

Simpson was determined to program diverse fare. In 1998, the Flea offered an opportunity to Irene Worth, grande dame of the theatre, to present The Letters of Georges Sands and Flaubert, and a similar berth for Karen Finley, whose National Endowment for the Arts grant had been revoked eight years earlier, to disrobe and revisit the controversy in her The Return of the Chocolate-Smeared Woman.

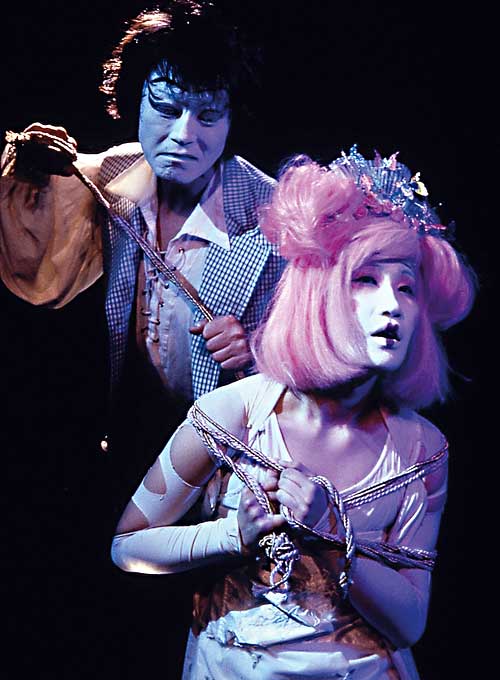

And he brought on an eager resident company of young people. They were originally called the Furballs, and they made up the cast of 29 in Benten Kozo, a 19th-century Japanese play that ran for six months. With 11 fight scenes, it struck Simpson as ideal for a youthful company. “We’re not going to do Chekhov. The work for the Bats has to be on edge socially, sexually, politically—because that’s the privilege of youth.”

By the fall of 2001, with Weaver’s seed money nearly run out, the Flea was buzzing with two plays in repertory, and scheduled dance and music concerts. Then 9/11 effectively shut down the neighborhood—the former World Trade Center towers were about a dozen blocks away from the theatre. Even when the area reopened, Simpson recalls, “Nobody wanted to come down; it was toxic, unpleasant, deeply sad. I was prepared to say: I guess that’s it. But the Bats said, ‘No, you have to respond to these events.’”

At a fundraiser for the Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, Simpson happened to sit down next to journalist Anne Nelson, who had just helped a fire captain on Staten Island write eulogies for his men who had died at the World Trade Center site. He told her to write it up as a play, and she did so, in a mere 11 days. Simpson cast Weaver in the play, her first Flea role, and got Bill Murray as her co-star. The response was enormous. “I always knew that a little theatre could make a difference in a community,” Simpson says. “I actually saw it happen with The Guys.”

Simpson had just hired his former Yale classmate Carol Ostrow to be the Flea’s producing director, and, with the help of ICM agent Sam Cohn (“He loved the Flea,” says Ostrow), she installed a different starry cast every six weeks. The Guys ran for a year. It was a turning point for the Flea.

Ostrow, who had founded the Powerhouse Theater at Vassar and revamped Classic Stage Company, imposed some administrative order on the reigning artistic chaos, putting together a real board, creating a budget and introducing herself to the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs. “I love living in chaos, being one with the chaos—that’s what artistic endeavors are like.”

When Swoosie Kurtz assumed the role in The Guys, she invited her friend the playwright A.R. Gurney to see it. “This play was such a strong, simple response to the recent disaster, and worked so well in that intimate space,” Gurney says, “that the next day I sent my own play on to the director.”

The play, O Jerusalem, was Gurney’s response to 9/11, with a Palestinian character and an anti-Bush theme. “My usual venues didn’t want to touch it,” says the author best-known for such genteel comedies as The Dining Room, Love Letters and The Cocktail Hour. “I had pretty much decided my game was over.” Gurney was impressed with Simpson’s “passionate” production of his play, and his use of a “shadow cast” of Bats, whom he rehearsed in the evening “in order to experiment with various ways of staging the play. He then might try out alternate staging on the regular cast of actors the next day. I was sold on the whole Flea experience—the youthful back-ups, the collaborative atmosphere, and what turned out to be enthusiastic audiences.”

Gurney has been writing for them ever since, with some plays written specifically for the Bats. “The Flea gave me the energy and love of the profession I thought I had lost.”

Simpson and Ostrow decided the Flea needed its own building in 2005: They craved more space and the landlord wouldn’t let them expand within the building. In any case, the rent was steadily rising. They found the building they wanted in 2007 and were finally able to purchase it in 2009. The last five years have been spent raising the money to renovate it; about half the money comes from state and city funds, much of it earmarked to counter the effects of 9/11; about half from private donations. They still have $100,000 left to go, but they decided it was time to thank their donors with a groundbreaking.

“This transition is very challenging,” says Simpson. Part of that challenge, he concedes, is the greater scrutiny to which the company has been subjected. Some former Bats who wished to remain anonymous said that while they appreciated the chance to do interesting work at the Flea, they eventually chafed at the expectation that they would not only rehearse and perform without pay, but also clean bathrooms and perform administrative tasks at the theatre for free.

Other former Bats readily go to bat for the company. “The Flea was my graduate school,” says actress and producer Jocelyn Kuritsky, who also praises the leadership. “Jim has a keen interest in a diverse company, and he will go after some really unusual talent. I know there’s always been a lot of debate about the Bats and the ethics of using the Bats as unpaid labor for the theatre. But the truth is that an actor’s work in the theatre, by and large, is often unpaid or super-underpaid. This is a much bigger problem, one that surpasses the Flea.”

Critics like Butler wouldn’t disagree. The Flea isn’t the only company that seems to put more money into new buildings than into new talent. “Institutions are constructing ever bigger and shinier buildings, and more and more people are leaving the industry because they can’t afford to work in it.”

Simpson sees this differently. “It’s a good thing to have a lot of theatres built. Like it or not, theatre has a really close relationship with real estate. The possibility of gaining employment is better with more shiny buildings rather than fewer.” Among donors, he adds, “there’s more support for capital funding, more comfort with things than with people. That’s just the nature of investment.” Still, he says, “I’m sensitive to the discussion that is happening; we’re actively looking for how to resolve this issue.”

It is one of several issues Jim Simpson would like to resolve before handing over the Flea to the next generation, which he aims to do sooner rather than later, to “people who share our vision, or have a better vision.”

In the meantime, Simpson hasn’t shed his eclectic ambitions. “I’d love to do The Sound of Music,” Simpson says. “That’s on my bucket list.”

Jonathan Mandell writes frequently for this magazine and tweets as @NewYorkTheater.