Ira Aldridge is finally getting his due.

The expatriate African-American Shakespearean actor (1807–1867), who made a name for himself as an actor in London and is one of the most celebrated artists of his time for breaking gender and racial barriers onstage, is at long last receiving recognition in the land of his birth. However, portraying someone of such legendary stature can be daunting—even for the most talented of performers.

“Oh, my goodness, it’s a huge challenge!” exclaims actor Adrian Lester, who received the London Critics’ Circle award for best actor for his portrayal of Aldridge in Lolita Chakrabarti’s Red Velvet at London’s Tricycle Theatre last season. The company remounted the production in January, and it is transferring, with its full British cast intact, to St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn for its North American premiere this month. Performances begin March 25 and are scheduled to run through April 20.

But the Aldridge renaissance started long before Red Velvet’s U.S. debut. First came the rave reviews for Bernth Lindfors’s magnificent two-volume biography of Aldridge, published in 2011, which was preceded, in 2007, by an equally impressive collection of essays (edited by Lindfors) from a stable of international scholars who addressed aspects of Aldridge’s life on and off the stage. In his books, Lindfors also dedicates a sincere tribute to two important previous works on Aldridge and black Shakespeareans in general: Ira Aldridge: The Negro Tragedian by Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock (1958) and Shakespeare in Sable: A History of Black Shakespearean Actors by Errol Hill (1986).

Last July, Alex Ross wrote an article in the New Yorker that began as an homage of sorts to Luranah Aldridge, one of Aldridge’s five children, and then doubled back to cover the life and times of her famous father. Luranah’s professional life as an opera singer was not without its own significant achievements—Ross contends that she should be given credit for unofficially breaking the color barrier at the Bayreuth Festival 65 years before Grace Bumbry’s triumphant performance there in 1961. She must have inherited her trailblazing sensibilities from her father.

“When you get into the question of style with regard to classical acting in the 19th century, it only gets more complicated,” Lester says, speaking to Aldridge’s own innovation as an actor. “We brought in Sophie Duncan, an expert on 19th-century acting styles, to confront this problem. In the very critical time period in which the play takes place—as Aldridge is about to do Othello at Covent Garden in 1833—he is developing his own unique approach to acting Shakespeare, and he is critical of some of the more formalized, declamatory acting styles of the period, as exemplified by actors like Charles Kemble, who would seem quite stilted—almost comical—if we could see them today. We wanted to open up this discussion that Aldridge was so passionate about. But as a result, the actual amount of Aldridge acting Shakespeare as it might have been acted in the 19th century is very limited. The play only concerns his portrayal of Othello.”

Lester seems to be up for the challenge. In his review of Red Velvet for the Guardian, Michael Billington wrote that, “What is striking about Lester’s performance is its emphasis on the novelty of Aldridge’s approach: It was his insistence on direct physical and emotional contact with his Desdemona, as well as his color, that caused consternation.” Coincidentally, after Red Velvet in 2012, Lester played Othello in 2013 at the National Theatre, directed by Nicholas Hytner.

Playwright Chakrabarti is not the first to see the life of Ira Aldridge as a compelling story that lends itself to the stage. Noted actor, playwright and director Ossie Davis wrote and produced Curtain Call, Mr. Aldridge, Sir in 1963. British playwright David Pownall’s script, Black Star, was staged in England in 1987, followed by Splendid Mummer, a monodrama tour de force by Lonne Elder III starring Charles S. Dutton, produced by New York City’s American Place Theatre in 1988 and directed by Woodie King Jr. There is also an early screenplay by Herbert Marshall that exists in his collection of Aldridge-centered manuscripts and research material at Southern Illinois University. The screenplay situated entirely around Aldridge’s experiences touring Russia and his acquaintances with the literary establishment of the day, including the artist Fyodor Petrovich Tolstoy and the revolutionary Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko, among others.

Marshall was the director of the Center for Soviet and East European Studies in the Performing Arts at SIU. He was hoping to attract Paul Robeson to do the narration for the film, but financing from Leningrad Documentary Film Studios never materialized. (Full disclosure: This list must also include Black Theatre Canada’s production of African Roscius (Being the Life and Times of Ira Aldridge) written by myself and produced by Vera Cudjoe in 1987 at the Alumnae Theatre in Toronto.)

In life, Aldridge was nothing if not an object constantly in motion. When he was 18, the peripatetic actor left his home in New York City—where he had played roles at the famed African Grove, one of America’s first African-American theatres—because he believed that his aspirations to take on the great classical roles could never be realized in the U.S. After his arrival in England, he promptly began to make a name for himself and received mixed critical reviews for his performance in Othello and The Revolt of Surinam; The Slave’s Revenge (adapted from Aphra Benn’s short story, Oroonoko). By 1833 he was finding the London critics a hard nut to crack (some of them were vehemently racist about the notion of a black man playing Othello), so he lit out for the British provinces, Ireland and Scotland, where he spent several years touring. There he sharpened his craft as an actor while simultaneously learning the business of the theatre.

When he was growing up in Oakland, Calif., Ted Lange became aware of Aldridge Players West, a pioneering black theatre ensemble founded in 1964 led by Henrietta Harris. “That was the first time I had heard about Ira Aldridge,” Lange recalls. Lange, fondly remembered as the bartender on the TV series “The Love Boat,” cut his teeth with the New Shakespeare Company (NSC) of San Francisco, doing free performances in Golden Gate Park in the 1960s.

“When I had an opportunity to do Shakespeare with NSC in 1967–68, I began to look more deeply into the amazing career of Ira Aldridge. Margaret Roma, the director of the company, posted a reading list for the theatre that had Stanislavski, Artaud, Jan Kott, Margaret Webster, Peter Brook—the standard stuff for actors—but also the biographies of Paul Robeson and Ira Aldridge. Roma cast me as Romeo and believed strongly that a classical repertory company in America should reflect racial diversity, not unlike what Joe Papp was doing in New York at the same time.”

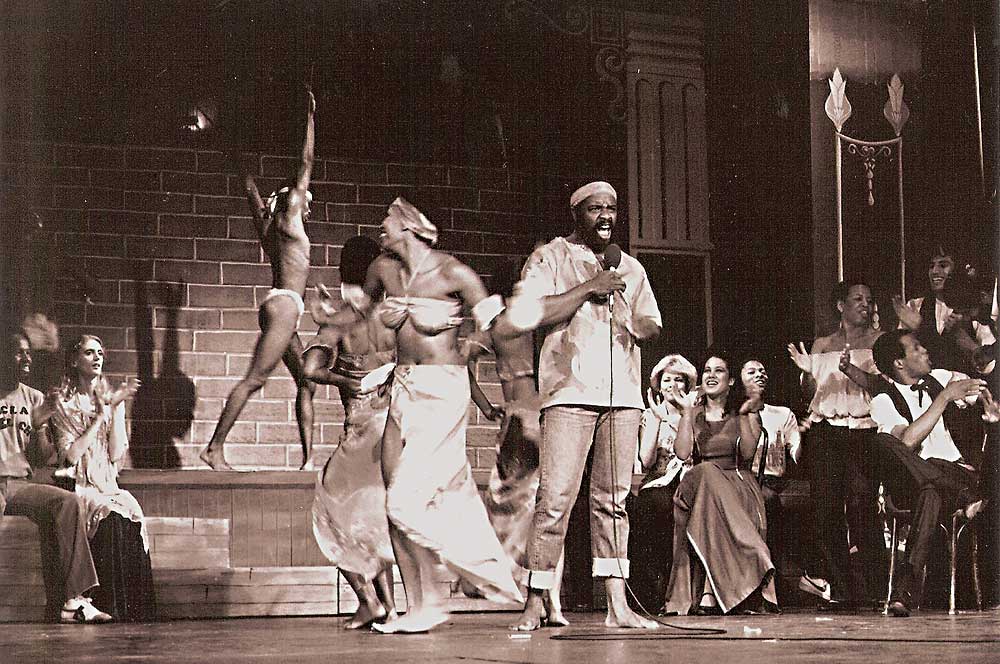

Lange’s rock musical based on the life of Aldridge, entitled Born a Unicorn, originally premiered at the Inner City Cultural Center in Los Angeles in 1981, featuring Charles Weldon as Aldridge, and was remounted by the North Carolina Black Repertory Company in 2012. The show is perhaps the only dramatic adaptation of Aldridge’s life to date that incorporates music. “I wanted to reach out to young people at the Inner City Cultural Center in 1981,” says Lange. “I wrote and directed the piece and got two great people, Beverly Bremers and Phyllis St. James, who wrote the music and lyrics. The score is a combination of rock, blues and a bit of gospel.”

Charles S. Dutton first learned about Ira Aldridge in 1981 when he was a student at the Yale School of Drama. “I was taking a theatre history course with professor Jonathan Marks, who talked about the great Shakespearean actors in history, and he mentioned Ira Aldridge,” Dulton remembers. “I had never heard of him, so I went to the library and found the book by Herbert Marshall and Mildred Stock. It was published in 1958 but had only been checked out of the library twice in 23 years! As I leafed through the book, which is chock full of photographs, playbills of the period, etc., I must have become a bit emotional because the librarian just said to me, ‘You should have this book. I will order another one for the library.’

“Several years later when I was doing Splendid Mummer, at the American Place Theatre, I got a knock on my dressing room door one night. It was Herbert Marshall! He had heard about the play in London and immediately gotten on a plane, and come to New York just to see me as Aldridge. I was deeply touched, to say the least.”

Speaking about acting Shakespeare, Dutton says, “At Yale, Lloyd Richards once said to me that you should really play the great classical roles three times in your career. Once when you are young, again in middle age and again when you’ve reached maturity in age. As a young, brash know-it-all doing Othello for the first time, I really didn’t get what he meant, but now I do. As much as I enjoyed doing Splendid Mummer, there really wasn’t much opportunity to act Shakespeare in the script. I’d like to revisit it sometime and insert more Shakespeare. I’d like to try it again.”

Aldridge too wanted to define his career by the Shakespearean roles in his repertoire, and he soon moved to expand his reach by including Lear, Macbeth, Richard III and Shylock. In applying whiteface makeup for Shylock, he was said to have always left his hands black because he wanted his audience to make the connection between racism and anti-Semitism. He even mounted a bowdlerized version (a common practice with Shakespeare in the 19th century) of Titus Andronicus in which he rewrote the role of Aaron the Moor so that he became the hero of the play.

The trailblazing breakthroughs in choosing roles that Aldridge made in the 19th century we would today refer to in a more codified way as “nontraditional casting.” He even incorporated cross-gender roles, appearing as a maid in one of his more celebrated afterpieces.

But Aldridge was about much more than uplifting his race through affirmative action. Carrying more than 40 plays in his repertory, spanning the classical to the popular melodramas of his day, Aldridge stands as a standard-bearer for all who came after. He worked until he died, in Lodz, Poland, while rehearsing a production of Othello in 1867. His gravesite today is a shrine tended by the Society of Polish Artists of Film and Theatre.

When Adrian Lester walks out on the stage of St Ann’s Warehouse as Ira Aldridge, the critics will once again have an opportunity to parse his work. But what they will see in Red Velvet is only a narrow sliver of Aldridge’s life at a pivotal juncture in 1833 when he was still only 25 years old—that is, before Aldridge really became Aldridge.

Dutton puts it this way: “It might look as though Ira Aldridge left America and, as a result, was able to achieve huge success, both artistic as well as financial, while living abroad. But his life certainly wasn’t all peaches and cream. He led a very public life and had to withstand a huge amount of racism in his day. But at least he was able to have a career.”

Robin Breon is an independent arts journalist and playwright based in Toronto.