“I want to work on a little Yiddish today,” announces David Herskovits, artistic director of Target Margin Theater, at the outset of a rehearsal.

I’m sitting in a studio in Brooklyn with Target Margin’s cast and crew, at work on Uriel Acosta: Doubt Is the Food of Faith, a piece based on a series of Yiddish, Hebrew and German plays about a controversial 17th-century Jewish philosopher. The show is scheduled to open in March at the Chocolate Factory in New York under Herskovits’s direction. (Full disclosure: I’m the supervising dramaturg for this production.) Right now, the atmosphere feels more like a graduate seminar than a theatre rehearsal.

Everyone has a binder of source material with notes scribbled in the margins: half a dozen different versions of the play in partial translation; memoirs of Yiddish actors who once performed in it; historical documents about the real-life Uriel Acosta; philosophical treatises and Rabbinic responsa; material from Yiddish-theatre histories; selections from other Yiddish dramas, poetry, short stories and novels.

The actors begin reading from one text, then another. The assignment is to find words, phrases and lines that the company might consider translating and performing in Yiddish. Scarcely a line goes by without comment:

— “I am here at your wish, dear friend.”

—“You are here only at a woman’s wish? Oh, Uriel Acosta, where have you been?”

“I have ‘oh’ in Yiddish,” Herskovits interjects. “I’m sure it’s not pronounced ‘oh.’ Or it might be.”

“Oy?” someone ventures. Everyone laughs.

“Or akh?” another actor suggests.

“I want the whole line in Yiddish,” specifies assistant director Nick Trotta. “Definitely Yiddish.”

Piece by piece, line by line, layering different versions and languages on top of one another, Target Margin is building a script that is neither translation nor adaptation. It’s a dramaturgically rigorous amalgamation, layered with virtually anything that the company thinks might shed light on the experience of an obscure Jewish rebel from the 1600s. Past rehearsals have paired iconic Yiddish films of the 1930s with camp and burlesque films by performance artist Jack Smith; today Herskovits has invited video artist Maya Ciarrocchi to screen Frei (Free), her short film about former ultra-Orthodox Jews who have chosen to leave their communities and lead secular lives.

“Did anything that you saw or heard resonate with you about this play?” Herskovits asks as the screening concludes. The response is an enthusiastic yes. Many of the actors have pages and pages of notes. They quote from the film as they compare Acosta’s long-ago secular rebellion with the experience of contemporary Hasidic Jews confronting similar dilemmas in Crown Heights or Borough Park, just a few subway stops away.

“Watching that, I felt like it was exactly Uriel,” says Trotta. “He’s so fed up, he’s so angry, and he feels betrayed!”

“We might sort of borrow a sentence here or there,” Herskovits ventures to videographer Ciarrocchi. “You might hear that language coming up. Are we allowed to do that?”

“They would be thrilled,” she replies. And so it goes—Target Margin’s reconstruction of Uriel Acosta piece by amalgamated piece, a mash-up of Yiddish and English, the historical and the contemporary, text and commentary.

For Herskovits, that’s precisely the appeal of this play. “There is no original version of this story, and there’s no original version of the character,” he says. “What I’m doing is taking as many different versions as I can find, and trying to steal from all of them the things that will tell the most vivid version of the story that will speak today. It’s going to be ours. And it’s going to be yours.”

Herskovits wasn’t always interested in Yiddish theatre. Prior to embarking on this project, he admits, he had never given Yiddish culture much thought—it was Fiddler on the Roof and comedy, schmaltz and borscht. But one day, while on a family trip to San Francisco, Herskovits happened upon an exhibit at the Contemporary Jewish Museum entitled “Chagall and the Artists of the Russian Jewish Theater.” It was an epiphany.

“That hour in the museum, the scales fell from my eyes,” Herskovits recalls. “It just revolutionized me. I looked at this stuff and I felt myself connected to it artistically. Not primarily as a Jew, but just as a person interested in the creative imagination and its adventure.”

Almost universally, those who have been involved in Target Margin’s Yiddish project Beyond the Pale, an exploration of Yiddish culture onstage now in its second and final season, talk about their experience as kind of personal journey. The company’s artistic producer John Del Gaudio, who has spent the past two and a half years reading virtually everything ever published in English about Yiddish literature, tells me that he had never imagined that Yiddish culture would have so much to offer. Sitting in Target Margin’s office surrounded by piles of Yiddish literature, archival material and secondary reading, he shows me drawers of books that he’s renewed 13 times from the local library.

“In my family, Yiddish was not seen as a language of intellectual culture,” adds Raymond Blankenhorn, a young director who has worked on the Beyond the Pale program in several capacities. “The discovery for me was that this is a language and culture of artistic seriousness.” Blankenhorn’s grandmother had rejected her Jewish upbringing to lead a secular life in New York City; when her grandson told her that he was working on a Yiddish theatre project, she was baffled. But when Target Margin’s production of The (*) Inn opened last spring, she was there, age 90.

It is precisely this experience—this journey of discovering the treasure trove of Yiddish theatre—that Target Margin seeks to bring to audiences. “In the context of such narrow presumptions about Yiddish,” Herskovits confides, “it is especially exciting to open the door to this universe. You think that you’re looking at a very small house, but when you open the door, it’s a fantastic mansion inside. That’s the experience that I had.”

Uriel Acosta will be the penultimate program in Target Margin’s two-year series of Yiddish programming. By June, the company will have tackled some 23 productions inspired by Yiddish literature, in addition to dozens of staged readings, lectures, roundtables, workshops, poetry readings and other events.

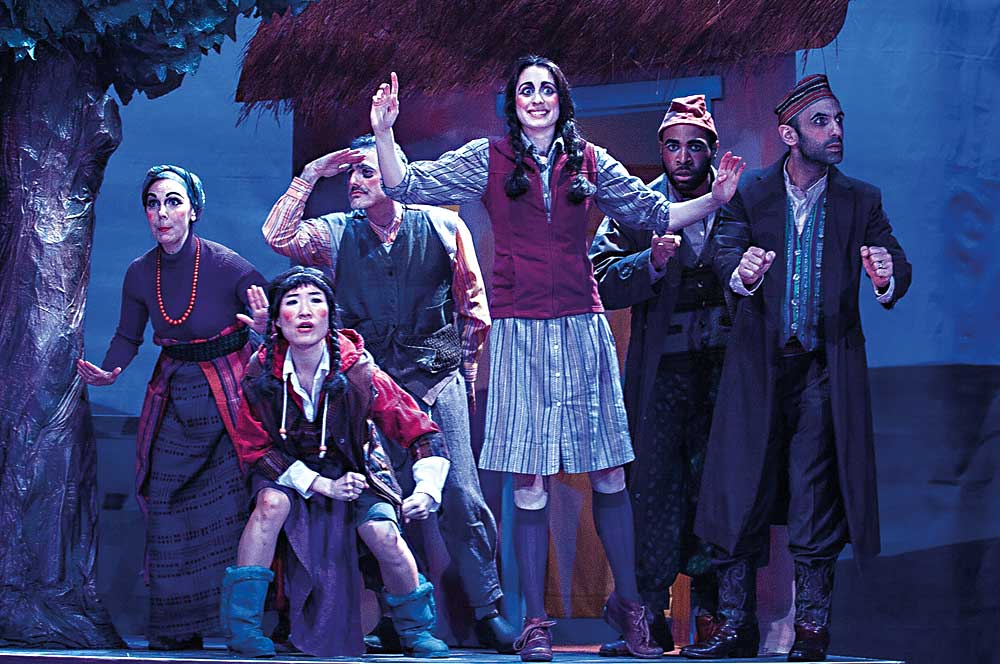

Last year, the company presented a “Lab” of seven small-scale experimental productions of Yiddish plays, and a full production of Peretz Hirschbein’s The Haunted Inn (performed under the intentionally enigmatic title The (*) Inn), an in-your-face expressionist shtetl drama that the program described as “Tevye on drugs.” This year, the lineup boasts three labs of four or five shows each; performances and workshops at the New York Public Library, the JCC and Baruch College; and an initiative to commission new translations of never-before-translated Yiddish plays, as well as the spring production of Uriel Acosta.

If last year’s season was about introducing Target Margin’s audience to the range of Yiddish drama, this season aspires to engage with the entire corpus of Yiddish literature and culture, and, in particular, the tradition of adaptation that was so prevalent on the historical Yiddish stage. The focus has shifted to adapting different types of Yiddish material (poetry, novels, music, short stories, etc.) to generate new work. A December lab featured four pieces based on Yiddish poetry, each of which offered a different interpretation. The lead artists crowded into Target Margin’s offices and spent hours reading Yiddish poetry until each of them found something—a poet, an aesthetic movement, a theme—that resonated. William Burke, a playwright who was one of the four lead artists for the winter lab, became so enamored with the early-20th-century poet Moyshe-Leyb Halpern that he ultimately composed several original poems in Halpern’s signature style, which then became the conclusion of the show.

“A lot of Halpern’s poems are about New York, and, while poetic and well rendered, they’re very similar to conversations I have with people I know who are trying to figure out this city and trying to figure out being an artist,” Burke says. “It’s very theatrical. You just want to hear it out loud. It’s the next logical step.”

The result of Burke’s encounter with Halpern was an original piece that featured actors reciting poetry into vintage Victrola horns. Burke’s piece was on a double bill with another production inspired by the same poet, Emily Rea’s Outside/In, for which Rea commissioned handmade bilingual Yiddish-English miniature books that provided audiences with both the original text and a translation for the poetry included. Another double bill paired an interpretation of the poetic response to the Triangle Factory fire with a piece that brought modernist poet Celia Dropkin’s poetry to life alongside whimsical projection art and acrobatic displays by Parkour tumblers.

To Blankenhorn, a lead artist for the December lab series, the diversity of productions on display offers further proof of the vitality of this Yiddish material. “Letting people have at this material without presenting a kind of orthodoxy about it—that’s how you prove that point. It shows that the material is robust, that people can take a crack at it from all of these angles. And when you step back and see the whole picture, what comes out is this incredible corpus.”

Jesse Freedman, Uriel Acostas’s “sound demon” (that’s Target Margin–speak for “sound designer”), recalls a memorable first rehearsal in which the director introduced himself with, “Hi, I’m David Herskovits and I’m directing this play, whatever it is.” Freedman is unusual among those working on Uriel because his background is in directing, designing and producing plays with a Jewish bent. He’s developed plays and dance pieces based on his own explorations of Talmudic material and has worked with other Yiddish theatre companies, most recently stage managing the New Yiddish Rep’s critically acclaimed production of Waiting for Godot in Yiddish translation.

But for Freedman, what Target Margin is doing is something entirely new: creating theatrical collaborations for people who have never even heard of Yiddish and know virtually nothing about it. Case in point: Early rehearsals involved the collective authorship of a 20-minute sketch about Uriel Acosta that fused German and Yiddish dramatic renderings of the story with actors’ memoirs, original songs written collaboratively by the company, and an extemporaneous conversation that happened in rehearsal about the best place to get bagels and lox in New York City.

“Our process has been to wander and meander in a seemingly distracted way,” Freedman tells me, “in order to move into a realm that goes beyond the nostalgic limitations of what we think Yiddish theatre is into something that could actually contain what it means to this moment and for this community. So the process has been, in effect, making a huge mess, and then looking at the mess and seeing what is going to stick.”

The real Uriel Acosta scandalized Amsterdam’s Jewish community by taking a public stand against the accepted doctrines of Rabbinic tradition. After being excommunicated multiple times for his heresy, Uriel ultimately recanted under pressure, then committed suicide. Uriel’s story was the subject of dozens of dramatic treatments beginning in the mid-19th century, but it became particularly popular on the Yiddish stage. For Herskovits, Uriel Acosta offers a compelling and universal story with resonance for contemporary audiences. “Here’s this individual who challenges the community around him—and he’s a mystery,” Herskovits reflects. “And we can’t deal with that.” A pause. “I mean, I’m Uriel Acosta, right? I hadn’t put it this way before, but we all are. And that’s what’s exciting—that we are all Uriel Acosta.”

The Beyond the Pale program will officially come to a close in June with Target Margin’s final Yiddish Lab series, but Herskovits is by no means done. Target Margin has no plans to become a Yiddish theatre—there are plenty of other companies that already do that, Herskovits knows—but there are related projects that he is interested in pursuing.

The encounter with Yiddish has been a transformative part of the company’s artistic journey, and for that of Herskovits himself. Standing in that museum exhibit years ago, the director realized that Yiddish is an integral part of his theatrical heritage as an experimental artist.

“My hope, between you and me,” Herskovits confides, “is that other people in the U.S. theatre, when they’re thinking about things to work on or plays to read, will say ‘Oh, yeah, I heard about that program—it sounded interesting. Let’s have a look.’ And what people will find is enormous potential for productions.”

Debra Caplan is an assistant professor of theatre at Baruch College, City University of New York, where she teaches courses on theatre history, drama and Jewish culture. She is currently writing a book about interwar Yiddish experimental theatre.