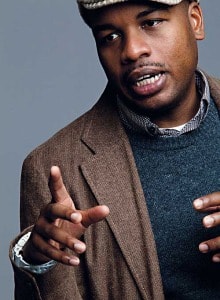

It’s hard to hear MARCUS GARDLEY ‘s name without making an aural connection to black nationalist Marcus Garvey. The prolific 36-year-old playwright’s work has also drawn comparisons to August Wilson. Given how often Wilson is held up as the yardstick for contemporary African-American dramatists, that may say as much about the (largely white) cultural commentariat as it does about Gardley’s work.

But after talking to Gardley, it’s clear that his influences—among which, he notes, Baldwin is most prominent—are wide-ranging and ever-expanding. And after reading just a few of his plays, it’s also clear that he possesses a poetic-yet-nuanced love for what time, circumstance and history have created in communities across the United States, as well as a nimble ability to re-imagine classic myths of all stripes.

Gardley has three world premieres running right now. Black Odyssey at Denver Center Theatre Company (through Feb. 16) takes Homer’s epic and recasts it as the contemporary story of a black soldier returning from Afghanistan. California’s Berkeley Repertory Theatre (in a co-production with Connecticut’s Yale Repertory Theatre) presents The House that will not Stand (through March 16), which takes the bones of Federico Garcia Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba and reanimates them in a home filled with “free women of color” in New Orleans, post–Louisiana Purchase and pre–Civil War.

And on Feb. 28, Chicago’s Victory Gardens Theater opens The Gospel of Lovingkindness, Gardley’s depiction of the toll of violence and the role of faith in Chicago’s Bronzeville, a South Side neighborhood as rich in cultural importance for African Americans as Gardley’s hometown of Oakland, Calif. (The latter play is Gardley’s first production in Chicago, where he is now enjoying a three-year residency at Victory Gardens as part of an initiative with the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.)

“I am obsessed with these stories that evolve over time,” says Gardley in a telephone interview on New Year’s Day; he has just landed in Berkeley for rehearsals after leaving Denver. “Stories in the Bible, but also Greek myth, creation stories, and how we need them in order to understand our humanity. I am also really obsessed with histories that are no longer in the popular consciousness—parts of our history that are taboo to discuss or that we just don’t know, for whatever reason.”

In the road weeps, the well runs dry—which ran at several theatres last year as part of Lark Play Development Center’s “Launching New Plays Into the Repertoire” program, including Perseverance Theatre in Juneau, Alaska, Pillsbury House Theatre in Minneapolis and the Los Angeles Theatre Center—Gardley examines the tangled connections between native Seminole and African-American families in Wewoka, Okla., before and after the Civil War, using Native American creation myths as part of the storytelling matrix.

Gardley, who earned his MFA at Yale, never saw a play before he began his undergrad career at San Francisco State University. The son of a minister and a nurse, he describes his childhood as one in which “we didn’t watch a lot of television. We read a lot of books. I read a lot of plays and wrote them before I saw one.” His academic plans morphed from pre-med (he planned on being an anesthesiologist) to French, inspired in part by Baldwin’s sojourn in Paris. But Gardley, unlike his inspiration, couldn’t afford the required last year in the French capital. “I was kind of distraught, so I took a playwriting class because I thought it would cheer me up,” he explains.

Despite his wide range of historical and mythical references, the first of Gardley’s works to gain critical attention began with stories close to his East Bay home, produced by Berkeley’s intrepid Shotgun Players. Shotgun’s founding artistic director, Patrick Dooley, first heard about Gardley at the 2005 Theatre Communications Group conference in Seattle. Dooley wanted to develop a piece about Shotgun’s South Berkeley home base, using some of the “story circle” techniques popularized by Los Angeles’s Cornerstone Theater Company. That led to Shotgun’s 2006 production of Love is a Dream House in Lorin, directed by Aaron Davidman of San Francisco’s now-defunct Jewish Theatre and featuring a cast of 30 actors and community residents relating stories of the economically and ethnically diverse neighborhood of the title.

“He stayed with us for a long period of time,” notes Dooley. “He lived with a neighbor in South Berkeley for a while.” (By the time the show was developed, Gardley was living in New York. Like Baldwin, he finds Harlem’s artistic scene inspiring.) “We did these incredible workshops and open meetings with the community,” Dooley adds. That show was followed by 2009’s This World in a Woman’s Hands, also directed by Davidman, dramatizing the “Rosie the Riveter” stories of women in the Richmond, Calif. shipyards during World War II. “He did something really beautiful and complex that wove in what was going on in Richmond now and what was going on 60 years ago,” says Dooley, who notes that the only male in the cast was celebrated jazz bassist Marcus Shelby, a member of the ensemble.

Strong roles for women and music as a spritiful and narritive force are hallmarks of Gardley’s work, which is particularly apparent in the script for The House that will not Stand, developed through Berkeley Rep’s Ground Floor new-plays lab. Madeleine Oldham, director of the Ground Floor (Patricia McGregor directs the production) says, “The way he writes women is extraordinary. I say that with hesitation because there shouldn’t be that distinction—but historically female roles in the theatre have been drastically underrepresented. I think Marcus is absolutely great at addressing that.”

Gardley credits his comfort with writing female characters to a near-mystical connection to a matriarchal family heritage. “The day I was born, my father’s grandmother died,” he says. “In our family, that was not seen as coincidental. They never said it that way, but they feel like I have her spirit or her energy.” Gardley also notes,“The women in my family have always treated me differently. They would allow me into their space when no other man was allowed.”

More practically, he adds, “When I started writing plays, I would go to auditions and notice that there weren’t enough roles for black actresses. I wasn’t writing enough parts for them. So I decided to draw from my experience and write more parts for these women.” Oldham says with a laugh that Gardley told her that he had to stop checking into his Facebook account during the auditions for the Berkeley Rep show, because so many women were online asking him for help in getting an audition slot.

In The House that will not Stand, a free black woman, Beartrice Albans, the widow of white New Orleans merchant Lazare and the mother of three marriageable daughters, struggles with the changes that have rocked her society after the French sell Louisiana to the United States at a time when slavery is still legal. Though the Lorca influences are visible, if one looks, Gardley has infused the tale with his own mix of lyricism and ribaldry. The holier-than-thou middle sister is named Maude Lynn, and she is indeed comically melodramatic. The older sister, Agnes, describes her youngest sister and rival for her lover’s affections, Odette, as “looking like you were born downwind of an outhouse.” The play is also suffused with music, from African bamboula drumming to Creole songs.

Gardley, who is fond of quoting Lorca’s observation that “a play is a poem standing up,” explains that his process often takes a while from initial inspiration to final product. To make the story his own, Gardley says, “What I do is read a lot for a couple of years. I do a lot of research. I read a lot about why Lorca wrote the play. And then I get rid of it in my writing space.”

“The way he reimagines is through character,” says Oldham. “He has a great imagination for the life of the character and why people are doing what they’re doing. Sometimes when people adapt things, they are overly reverential. He is respectful, but he uses them as springboards for his own imagination rather than feeling like he has to stay true to whatever happened originally.”

That may be true for the work that Gardley derives from existing literary and mythical sources, but for documentary-inspired work, he retains an underlying respect for the real people he’s portraying onstage. For This World in a Woman’s Hands, Dooley says, “He was writing a story that hadn’t been told, as far as we knew. He felt a tremendous amount of pressure to do that story justice.”

Gardley has had some high-stakes commissions in recent years. His 2010 play about hate crimes in the South, every tongue confess, opened Arena Stage’s new-works Kogod Cradle, in a production starring Phylicia Rashad and directed by Kenny Leon. Leon says he had heard of Gardley, but hadn’t encountered his work until he read every tongue. “I told him at our first meeting, ‘You’re the young prophet.’” Leon also cites the poetry in Gardley’s work. “I am drawn to all of those writers who have great poetry at the center of their writing—Tennessee Williams, Pearl Cleage, August Wilson.” And though Gardley is often inspired by ripped-from-the-headlines stories, Leon says, “He’s not just some hack saying, ‘I have a hot topic, so I’m going to write about this hot topic.’”

Few topics are as hot – and as depressing – as gun violence and the toll it has taken on young black people on Chicago’s South Side. Although the 2013 murder rate in the city dropped to the lowest level since 1965, the 2012 statistics placed Chicago at the top of the list with more than 500 killings. One of the most high-profile victims in 2013 was 15-year-old Hadiya Pendleton, who was shot to death a week after performing with her high school’s band and drill team at an event in Washington, D.C., for President Obama’s second inauguration. The First Lady attended her funeral on the South Side in February 2013.

In The Gospel of Lovingkindness, Gardley takes the Pendleton story and transforms it into a story about a teenage boy, Emmanuel, son of Mary Lee and Joe Black, whose promising future is snuffed out by another young man. The funeral service in the play takes on darkly comic tones, and Gardley also offers up some cutting critiques of the empty cant and false piety that has accompanied the mounting death toll in some of Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods.

Gardley had originally planned to write a play with music, Chicago is Burning, also set in Bronzeville and based on underground drag balls in the neighborhood. But when he and Victory Gardens artistic director Chay Yew, who is directing Black Odyssey and Lovingkindness, decided that piece wasn’t quite ready, Gardley took a leap into talking to Chicago residents about the violence they confronted. “The Hadiya Pendleton incident really struck a chord in me, and I became obsessed,” says Gardley, “probably because I grew up in a very violent neighborhood in Oakland. My parents were magicians—they kept our heads in books. The power of books and the imagination that oozes out of a book kept us safe.

“The people in Chicago were saying, ‘Tell my story,’” Gardley goes on. “I had never heard that before. The most common thing I heard is, ‘My neighborhood is not that bad.’” Gardley also notes—correctly—that the South Side is far larger than the North Side, yet “the whole area gets labeled as violent, and it’s just unfair.” He adds, “What really blew my mind was everybody was so adamant about the solution. They felt that the play had to have a solution, otherwise what good is it? ‘It’s not just another play about how bad our neighborhood is, is it?’ ‘We need more jobs.’ ‘We need more education.’ ‘You can’t worry about education if you need to feed your family.’”

Finally, Gardley says, what resonated most clearly was that people “are not loving themselves. People in Chicago have such a strong sense of legacy and why they migrated there—and the idea that they have not succeeded really devastates them.”

Redemption and hope do appear in Lovingkindness, which will use a variety of community gospel choirs throughout its run. Mary, in particular, morphs from a grieving mother into a sort of holy prophet figure who tries to erase the blood on the street where her son dies, saying, “Some grief is large. It needs, it wants to be worn out. So I’m wearing it like a good coat. I’m showing it off. Letting it have its day.”

Says Yew of Gardley, “He is one of the few playwrights committed to representing and speaking for a voiceless community. Marcus does that beautifully. He creates a tension between the mythic and the real and the historical and the present. In that way, he makes it his own. Even in early readings for Lovingkindness, when the actors were commenting on what certain passages meant to them, he used those stories and wove them into the play. You can’t tell what is real and what he’s invented. Once you enter that universe, you realize you are indeed a part of it.”

Unlike some of his peers, Gardley seems uninterested in translating his burgeoning profile into high-paying film and television work, though he notes that he has been approached “quite often.” “I’m tempted by the money, but theatre fulfills my political passion, my poetic passion,” he explains. “You can’t do that as much in TV or film. You have more control in the theatre, and I don’t want to give that up.”

Gardley’s key for staying focused and inspired, even amid the swirl of multiple commissions and productions, is character. “That is the most important thing. I am fascinated with people. Good playwrights have to love people—I really believe that.” And, he notes, if you keep your ears and heart open, “People will tell you all of their business. They will tell you the story of their lives and they won’t want anything from you.”

Kerry Reid is a Chicago-based freelance journalist and a frequent contributor to this magazine.