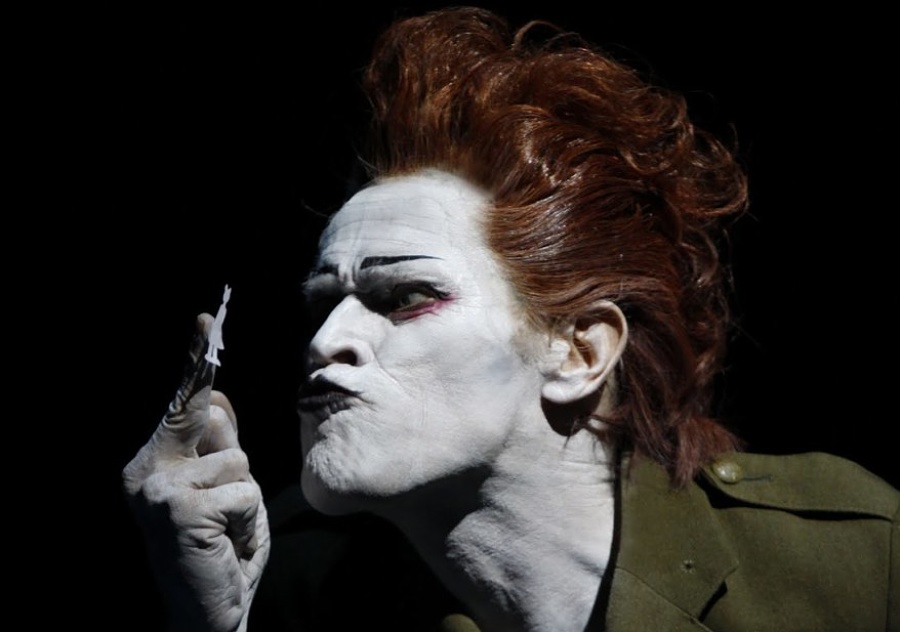

Willem Dafoe is an original member of the Wooster Group in New York City. This month, Dafoe appears in Robert Wilson’s The Life and Death of Marina Abramovic, which makes its U.S. debut at Park Avenue Armory in New York City Dec. 12–21. In June, the duo’s next collaboration, The Old Woman, will play at Brooklyn Academy of Music.

What compelled you to be part of Marina Abromovic?

The hook was Bob Wilson. I’d always wanted to work with Bob, and he was the one who invited me to come to the project. His form of theatre has some highly developed language, and that gives an actor a great amount of freedom, because the theatrical/gestural language that he has developed is so precise that you can really live in a full way inside that kind of articulation.

It seems like Wilson’s exaggerated gestures are similar to the work you’ve done before.

I had worked with the Wooster Group, and I had also worked with Richard Foreman [in Idiot Savant in 2009]. They’re very different forms of theatre, but they have certain things in common—it’s not naturalistic. You’re always performing with a great amount of tension in your body and mind. It’s not the kind of performing that comes from a place of great relaxation and naturalism. I’ve always been drawn to that, because it heightens the stakes. It elevates things. You can’t get by on charm, or things that are recognizable. It takes more concentration and plays into what is beautiful about the theatre, which is the poetic, the mystical, the nonsensical. Naturalism is very easy to corrupt with charm and personality.

What’s the difference between performance art and theatre?

I think I’ll pass on that question. See, I don’t have to know! In fact, I don’t want to know. I always look at the company I keep and what the proposal is for what we’re going to make, and that’s the attraction. I don’t really try to categorize what I’m doing. I think part of an actor’s job is to reinvent the process and reinvent the intention with each show. So if I start to make those distinctions, that threatens the flexibility that I’m trying to cultivate.

Is that why your previous works, and this new one, have been multidisciplinary?

Yes. I’m also drawn to strong directors. It’s also true in my film career. I like serving a central vision and being the doer of that person’s vision, helping them to do it, being the collaborator—not an interpreter, but being the thing itself.

So you wouldn’t want to be a director and impose your own vision?

I don’t think so. I like being a little irresponsible and a little free, and the mystery of not knowing what the work is. If you have to convey your vision to someone, it’s a different kind of responsibility. You have to believe in a certain kind of value or point of view that the play is going to convey. And I don’t enjoy being that far ahead of the game. I like working from a place of not knowing and going towards experience. Then that experience becomes the content of your performance. In the case of Marina Abromovic, my task was very clear. I had to help Bob figure out how we were going to handle all this text, because I basically had the whole text in the piece. So sometimes I stand outside the story, and sometimes I stand inside the story. It’s a beautiful back-and-forth.

Are there any already-written roles in the theatre you would want to do?

It’s hard to say. I don’t know what something is until I do it. If there was a role I knew I wanted to play, that kind of anticipates knowing what kind of pleasure or interest it holds for me. That probably serves my ego agenda too strongly. And my best theatre experiences are usually when I can abandon that, to some degree.

What three things would you take with you to a desert island?

My wife, a good pair of Speedos, and a knife. I’m practical.

Since you played the Green Goblin in the Spider-Man film, would you ever want to be in Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark?

[Laughs] I hadn’t thought about it, and I haven’t seen it. But maybe someday I will. Generally, I’m an adventurer and I like to go to new territory, so that would seem like a bit of a repeat.

What’s the secret to a long life in the theatre?

I’m probably a bad person to talk to about that. I was with one company working every day for 26 years—I don’t have the traditional theatre career. All I can say is, I stood by my theatre family and I stayed with them for a very long time, because I was committed to that kind of depth and that kind of development—to refine a process, a way of working.

If a young actor says to me, “Hey, I want to be a theatre actor, what do I do?” I would say: Find people’s work that you’re interested in and just get near it, no matter what you’re doing. Insinuate yourself in the process and before you know it, you may be part of it.