In his impassioned review of the current Broadway revival of The Glass Menagerie, Ben Brantley says that Cherry Jones’s lead performance is “one for the ages, an Amanda that may someday be spoken of with the awe that surrounds Laurette Taylor’s creation of the part nearly 70 years ago.” Indeed, that long-ago performance is legendary, and even Tennessee Williams lamented in 1949 “our immeasurable loss that Laurette Taylor’s performances were not preserved on the modern screen.”

Taylor’s performance may not have been adequately documented, but tucked in the stacks of the Columbia University libraries we do have a behind-the-scenes story of the original 1945–46 Broadway production, as told in a 1963 oral history interview given by the show’s co-producer, co-director and star (as Tom Wingfield), Eddie Dowling, to what is now the Columbia Center for Oral History.

Except where noted, the remarks and conversations I quote in the following account are as recollected by Dowling in that interview (“The Reminiscences of Eddie Dowling,” © Columbia University, permission granted).

Had it not been for a contentious (but ultimately fortunate) lunch meeting at Moore’s restaurant in 1944, the world might have been cluttered with a comedy called The Passionate Congressman instead of blessed with a drama called The Glass Menagerie. At that meeting, a Broadway multi-hyphenate named Eddie Dowling talked his way out of a contract to direct the comedy. He explained to that show’s producers: “I’m a one-play man, and I’m in love with this other play.”

The “other play” was a slender thing of just 50-odd pages. Dowling walked out of the lunch meeting not only released from his previous contract, but with a commitment from the investor to fund the entire production of the new play.

Yes, talent makes its way in the world, and surely we would have come to hear of Tennessee Williams sooner or later. But the “memory play” we now know as an American classic—and Williams’s first major play—faced plenty of obstacles, as Dowling would tell it years later.

Williams was a “sick, tormented boy” who’d “been through the wringer” when Dowling first met him. He had failed to make good use of Rockefeller and Guggenheim grants that his agent had secured for him; his play The Battle of Angels had closed almost as soon as it opened in Boston; and he was anxious to have a successful play to pay for private care for his beloved sister, Rose, who was languishing at Farmington State Hospital.

Whether he knew it or not, it seemed Williams had finally met the right person to realize his goal. Dowling was an experienced writer, director, producer and actor, and was the founding director of the USO camp shows. It didn’t hurt that Dowling had fallen “madly in love” with the play upon reading it.

A strong cast would be essential. Dowling knew right off who would be the perfect star: Laurette Taylor. Other people would have called the choice crazy. Dowling knew as well as anyone that she’d been “hibernating with a gin bottle for 12 years” in a room at the Hotel 14 on 60th Street.

He called her on the phone and asked, “Hello, is this Miss Taylor?” She said, “Hello, who is this, please? How did you get through to me? The word is downstairs that nobody is to get through to me that has to ask, ‘Is this Miss Taylor?’”

Dowling identified himself and said he had a play for her. “So do a lot of people have plays,” she retorted. “I’ve got plays, dozens of plays.”

“I think there’s only one living actress who could play this play,” Dowling came back.

“I’m not living. I’m dead,” she said. “I died when Hartley died.” Taylor’s husband J. Hartley Manners had died in 1928. “Don’t be bothering me.” But Dowling persisted.

“Well, supposing I liked it,” she relented. “What could you do with it? No manager would give you a theatre with me in the play. Don’t you know I’m anathema to all the managers on the Street? I’m Taylor, the drunkard. I’m Taylor, the bitch. I’m Taylor, all the lousy things that those bastards can think up to call me.”

Dowling assured her he could get a theatre. She allowed him to come over, and he found her “in her bare feet, with an old beaten kimono around her, and her hair all scraggly.”

It had been a long fall from the actress’s star-making turn, 30 years before, in Peg o’ My Heart, a play penned by her late husband. Dowling told her he had seen her in that role as a little boy, and seemed genuine in his praise. “God damn it, I think you mean that,” she told him, and promised to read the script.

Taylor may have been more interested than she let on. Her stage success had been early and phenomenal, but she hadn’t had a major role in years, not one that she hadn’t botched with her habit for drink, anyway. A late-in-life hit might just revive her spirits.

She called Dowling the next day and asked him to come over. When he arrived, she said, “Do you think Broadway, this bastardly place, will buy this lovely, delicate, fragile little thing?”

“This is what I’m betting on. But maybe you’re right,” Dowling had to admit. “Other people have said what you said. But I don’t listen to other people. If I like something, I do it.”

“All right,” Taylor agreed at length. “You’ve got your actress.”

And with that, Dowling had rounded up his cast, or what he called his “menagerie.” Anthony Ross, “a big boy who was mustered out of the Army because he was unstable”; Julie Haydon, “a girl everybody thought was a little off the beam, and painting Christmas cards, when I brought her on”; and Laurette Taylor, “this poor wreck out of a garret.” Dowling himself would star as Tom.

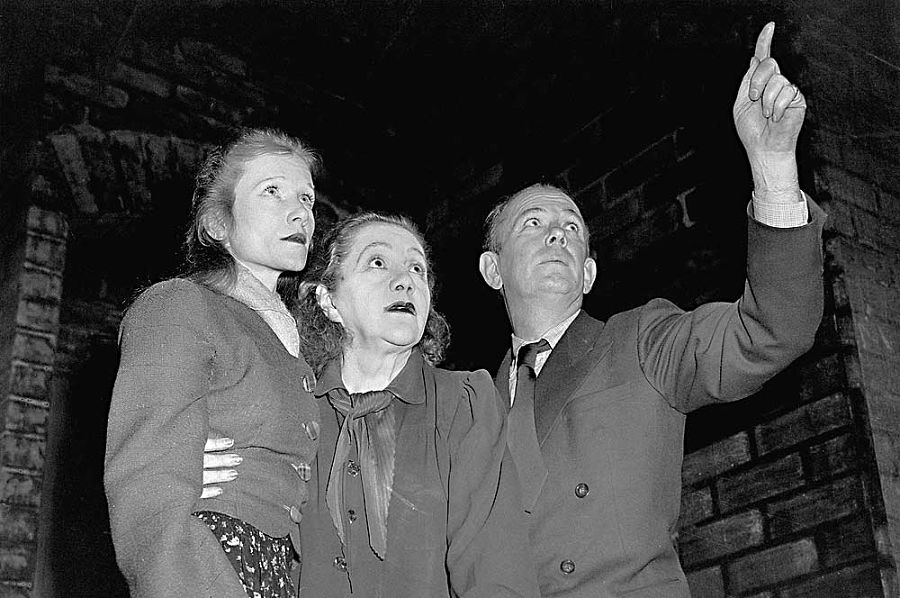

It was Christmastime, 1944, at a little French café and bar in the Theatre District, and the snow was piled high outside. Dowling had invited the cast and producers over for drinks before going to Chicago for the premiere of Menagerie there. Laurette Taylor and Anthony Ross begged off. But the investor Louis J. Singer came, as did Tennessee Williams; his friend and the show’s co-director Margo Jones; and actress Julie Haydon and her future husband, George Jean Nathan, a leading theatre critic. Nathan had been hearing bad things about the play in development.

When Dowling proposed a toast to Williams’s success, Nathan interjected: “Just a minute before you drink that toast. I don’t think there’s going to be [any big success] unless this young man takes out a lot of the delicatessen that’s in there—it’s still stunk up with a lot of Limburger he’s got to get out of there. If he doesn’t, you’ll be back before New Year’s. This play, according to the last reports Julie gave me, will die aborning.” And with that, he gathered up his things and left.

This prompted the financial backer Louis J. Singer to cry, “I knew it. [Many people] told me what a silly ass I was to put up all this money.” What Dowling had hoped would be an encouraging party ended on a sour note.

The era’s leading theatre critic had just trashed Williams’s play, and the money man had lost confidence. “Now don’t you worry,” Dowling advised the playwright. “This man Singer, in spite of what he says, has bet $50,000 on you. Miss Taylor has come out of an alcoholic hibernation. We’ve all got just as much at stake as you have.”

The play had a rough start in Chicago, losing thousands of dollars a week, but then turned a corner thanks to the tireless advocacy of some critics there. The next stop was New York City.

Opening night was Saturday, March 31, 1945, at the Playhouse Theatre. Dowling was “frightened stiff” that his leading lady would go back to the bottle. “She’d closed many a show on opening night,” he later recalled. To help prevent any drinking binges, he rehearsed the cast relentlessly, right up until 5 p.m. on opening night.

“We all kissed each other, hugged each other, prayed, did everything that people do on the eve of a thing like this,” Dowling continued. Then he released the actors and went for a walk with his wife. Upon returning to the theatre through the side alley, they saw Taylor at the bottom of a stepladder. Soaking wet. And plastered.

Dowling and his wife gave her coffee and stewed tomatoes from a tin, got her into the shower, walked her around. Meanwhile, the house filled up, and Dowling didn’t breathe a word to anyone of Taylor’s misstep. She took to the stage. After an initial stumble, the star came back and played “almost through a fog, but not a sign of the alcohol,” said Dowling. “I’ve never seen a performance like it in my whole life. It was something like out of another world.” The curtain came down to thunderous applause.

“For the first time in weeks she threw her arms around me,” Dowling would later recall. “She said, ‘Eddie, I can’t remember anything. Does it look like a success?’” By any measure, Taylor had nothing to worry about. In the New York Times, Lewis Nichols called her performance “all but incredible,” and Taylor a “great actress.” The reverence with which people spoke of her return would only increase in time, with Williams writing in a 1949 New York Times tribute of the “unfailing wonder of her performance,” and others calling it the role of a lifetime. By that time they were in a position to make such an appraisal; she had died.

Ecstatic reviews could only carry Taylor so far. As the months passed, “The thing that was sustaining her before was wearing thin,” Dowling could say with perfect hindsight. “She had had the adulation of the crowd. She had conquered New York. She had proven that she could do it.” But eventually it appeared that about the only thing she could fall back on was martinis.

Taylor’s faltering performances were noticed not just by Dowling but by a woman who came to see him named Laura Walker. A contemporary of Taylor’s who had become famous at about the same time, Walker had left the theatre more than 20 years before to marry a shipping magnate.

Walker asked if Dowling would put her in as understudy for Taylor. “I need it very bad,” she told him. “My husband is in pretty bad shape. We lost everything. It would be a godsend if you could put me on.” Moved by her story, and in need of a backup should Taylor’s increasingly erratic behavior become untenable, Dowling agreed.

The plan he concocted was to have an exact duplicate made of all Taylor’s clothes, and to have Walker sit in the front row at every performance. After a few weeks, Taylor caught on, and asked Dowling who the woman was. Dowling told her she was the new understudy.

“Do you mean,” Taylor asked him incredulously, “that you would keep this curtain up if I were ill or missed a performance?”

“Yes, Laurette,” he replied, “I’m going to keep the curtain up.”

In the following days, Taylor pouted, slammed doors and didn’t speak to Dowling. One blustery night, a year or more into the run, Taylor stalled for time well past the curtain. At last, the manager kicked in the star’s door. She was down on her knees with a bottle of liquor to her mouth. “How dare you do this to the audience!” said the manager. “Who do you think you are?” He shook her and pushed her out on stage, where she struggled mightily through her lines. After her first exit, she refused to finish the evening’s performance.

Dowling faced off with the audience in an effort to rescue the situation. “Seated here in the house we have an actress,” he told them in an impromptu speech, “who came up through the years and got to the point where she was a star and performing in this very theatre 25 years ago. She fell in love. You know, young beautiful actresses have a habit of doing this.” He explained how her husband had met with a reversal of fortune in both the physical and financial senses, and how she had asked to understudy for Laurette Taylor.

“So I know you’ve seen many, many Cinderella stories where the little girl in the chorus gets the chance to go on for the great prima donna, and she’s so great that the prima donna never came back. Well, that won’t be the case here. Now would you like to see an older Cinderella opportunity?” The audience roared its approval, and Walker picked up right where Taylor had left off. “This woman came in fresh,” Dowling would reflect nearly two decades later. “This woman had a dying husband. This woman had a cause. And like all people who are dedicated to a cause, she gave a performance that was magnificent.”

When everything quieted down, the phone rang for Dowling. It was Taylor asking, “How was she, Eddie?” He could only respond, “Laurette, she wasn’t you.” “You’re goddamned well right it wasn’t me,” Taylor said. “She’s an unnnnderstudy. I’ll beeee in, ssssweeethearttt.” Then she hung up.

Being replaced, if only for one performance, was a piercing blow to Taylor’s substantial ego: This career-defining performance might no longer be hers alone. She started to miss more and more performances until finally, one Saturday afternoon in June of 1946, something broke. Taylor was regaling stagehands with the story of her exploits that day at Schrafft’s, which, after an altercation with a hostess, had cut off the actress’s martini supply and had her ejected. “I was put out of Schrafft’s—me, the greatest actress in the world,” she told those assembled around her at the theatre. That included Dowling, who had her carried out to a taxi and taken home.

A police officer who had helped Taylor back to the theatre from Schrafft’s told Dowling, “I’ve watched her since I saw her in Peg o’ My Heart, and like every other man of our age I was in love with her.” Saying he spoke from experience lifting many alcoholics in 35 years in Times Square, he added, “That’s the last you’ll see of that lassie.”

It was indeed Taylor’s last performance, and the show’s triumphant if troubled run ended a short time later. Taylor called Dowling occasionally over the next few months, including one time in the winter of 1946 when she said, “I’m dying.” He teased, “You’ve been doing that a long time. When do you think it will happen?”

“You think I’m kidding?” Taylor replied. “I’m going to be laid out at Campbell’s at 81st and Madison, and it’s going to be bigger than Valentino. Everybody is going to come and genuflect; everybody is going to turn out for Taylor. It’s going to be some show. But goddamn you, don’t you come—don’t you dare come to the undertaking parlor when I’m in that beautiful bronze casket that I bought, because if you do, I know you’ll have that goddamn understudy with you and I’ll get up in the box and I’ll spit in her eye.” Taylor was dead before Christmas.

The original run of The Glass Menagerie had effectively launched Williams’s career and been the capstone to Taylor’s. Reading between the lines of the interview with Dowling, one might surmise that it was also the defining moment, happening at mid-career, for Dowling himself. Though the tapes of that interview have long since been destroyed, the reader of the transcript can almost hear the pride in his voice as he tells of how he extracted himself from his contract for The Passionate Congressman, or persuaded Taylor to perform. There is a touch of regret as he refers, albeit briefly, to a “horrible mistake” he made with a certain scene of the play while in rehearsal; one wonders if that unspecified mistake is what caused Williams never to work with him again, a fact which evidently pained Dowling greatly, especially considering that, in Dowling’s eyes, Williams “was born under my auspices.” However, for all the struggles of the production, Dowling concluded, “We do have the satisfaction of knowing that we did his finest play.”

Paul VanDeCarr is a freelancer in New York City, who writes on the many forms of storytelling. An audio dramatization of “The Reminiscences of Eddie Dowling” can be heard here.