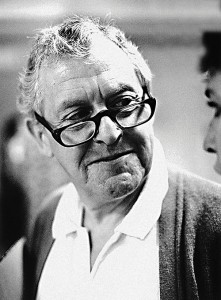

The photos on my wall leap out at me as vivid invocations of the late, great actor and teacher Jeremy Geidt. His rotund, sometimes bearded features and mischievous eyes are gazing toward a host of fellow players, over a period of almost 50 years.

When I met Jeremy, in 1966, he was a member of Peter Cook’s touring The Establishment Club, a satiric English troupe following in the footsteps of Beyond the Fringe. Learning that he and his Arkansas-born wife Jan were eager to find an artistic home in America, I invited Jeremy to teach, and Jan to administer, at Yale School of Drama, where he could act with the newly formed Yale Repertory Theatre.

Apart from the fact that he never quite lost his Regent Street accent, Jeremy was the perfect model for our budding American resident company. He had trained with Michel Saint-Denis at the Old Vic School, and, as a result, he was comfortable in a wide range of roles and styles, in productions as diverse as the late David Wheeler’s Waiting for Godot (opposite Alvin Epstein) and five Wheeler-directed Shaw plays, where he played all the patriarchs. He was in Ron Daniels’s Henriad, playing Falstaff, and Robert Wilson’s the CIVIL warS, and my Pirandello trilogy. At the same time, he was teaching a mask class which floated on the obscene air of bawdy improvisations, as well as, later, a Harvard undergraduate course in Shakespeare which won prizes every year.

He responded to any role, to any director, to any play, with the same bubbling enthusiasm that a young actor might show toward his or her first stage opportunity. And this was a man who knew how to transform from character to character. One of the hazards of company work is that audiences may tire of your face. They were never tired of looking at Jeremy’s, because it was rarely the same.

The photos on my wall show him as Engstrand in Ghosts ogling Cherry Jones’s Regina lubriciously through a window; as Osip, cynical servant of Mark Linn-Baker’s Khlestakov in The Inspector General, directed by Peter Sellars; playing Pantalone in two Gozzi plays, The King Stag (directed by Andrei Serban) and The Serpent Woman, once again opposite Cherry Jones; downing a tankard of ale as Falstaff, as he and Bill Camp, playing Hal, lounge lazily in front of a TV set; growling as the Old Shepherd in The Winter’s Tale, opposite John Douglas Thompson and Karen MacDonald; sitting languorously outside a sumptuous summer house as Gaev, brother to Claire Bloom’s Ranevskya in The Cherry Orchard; rehearsing Pyramus (Chuck Levin) and Thisbe (Joe Grifasi) in a forest where Carmen de Lavallade’s Titania and Christopher Lloyd’s Oberon crawl down Anthony Straiges’s wooden scoop, then stage-managing it as Peter Quince, in Epstein’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, before a court audience that includes Meryl Streep as Helena; identifying Yorick’s skull as the Gravedigger in Hamlet for Mark Rylance’s melancholy Prince; mocking Will LeBow’s Shylock as Salerio; and chastening F. Murray Abraham’s King Lear as Kent.

This is just a sampling of the more than 150 roles that Jeremy played with Yale Rep, and, later, when we moved to Harvard, with the American Repertory Theater. I will mention as a staggering fact that he spent more than 47 seasons with my two companies, the only even distant competitors being Tommy Derrah (30), Epstein (27), MacDonald (25), Jones (13) and LeBow (13).

An ideal artist, mentor and teacher, Jeremy was also the perfect pal, loyal and loving to an extreme. Totally devoted to the company ideal, he consistently rejected lucrative acting offers from New York and Hollywood in order to remain with the resident company and fulfill his obligations to students, both at the college and the ART Institute. I never heard him once say he regretted it.

What he valued more than fame or money was advancing his art and that of other people dedicated to the same cause. He delighted in seeing some of the students he had trained at Yale go on to join him as founding members of ART, just as he delighted in the success of others if they found a place in the world of Broadway, television or film.

But Jeremy was rooted. He loved the home on Garden Street that he shared for 34 years with Jan and his gifted, devoted daughters, Sophie and Jennifer. When they bought it, Jan and Jeremy worried that it would be too small. But anyone who visited them found the place so crammed with books, photos, paintings, posters and reviews that it seemed as vast as the lobby of a theatre. Being with Jeremy was always like being at the Mermaid Tavern before or after a show. He had bawdy names for everyone (I called him Fartola—he called me Fartissimo).

I hope the Mermaid is one of your destinations, dear old heart. But you will be sorely missed at your Cambridge pit-stops. Everyone who values theatre, actors and larger-than-life characters deserves a share of your wit, a dose of your ribaldry, a taste of your friendship.

Robert Brustein founded Yale Repertory Theatre and American Repertory Theater.