Of course I remember 1963. That was my first season covering theatre for the Minneapolis Tribune, replacing an old-timer whose reviews had been getting shorter and shorter.

I, of course, had plenty to say. “How old is Dan Sullivan anyway?” a reader inquired after my first reviews appeared. The answer was 27, and I was impatient with such retrograde entertainments as the Ice Follies and The Sound of Music. Wake up, Minneapolis! It’s the ’60s!

Actually, it was still the ’50s, with New Frontier trimmings. (“Mad Men” got it right.) Everybody smoked, nobody wore seatbelts, dumb blondes were funny, Jackie Kennedy was a paragon of womanhood, Jackie Robinson was a credit to his race, and America was the light of the world.

We all believed this, even our sophisticated young critic, recently returned from his brother’s graduation at the Air Force Academy, where jet fighters roared overhead. It was a dangerous world, and our cool young president was trying to rebalance it, de-emphasizing the Cold War and newly emphasizing the importance of the arts. (Jackie’s doing, probably, and good for her.)

My editor was even using phrases like “the cultural explosion,” referring to a story “we’ve got a responsibility to cover.” But then, we already were. The Guthrie Theater was coming.

Nationally, internationally and personally, this was a big deal. Sir Tyrone Guthrie was an authentic theatre giant, and my boss, John Cowles Jr., had spearheaded the campaign to build him a new $2.5-million repertory theatre in Minneapolis.

I couldn’t wait for the theatre’s first show—Hamlet, starring George Grizzard. Or maybe I could wait, for a lot would ride on my review. I remembered Joseph Cotten as the sellout music critic in Citizen Kane. Note to self: Don’t watch Citizen Kane. Do brush up your Shakespeare. And try to watch a rehearsal. Otherwise, play it by ear.

Why wasn’t I more intimidated? Because John Cowles Jr. was a civilized man, nothing like Orson Welles. Also because no one at the paper was sending me discreet little signals that the people upstairs might want to take an advance look at my review—just in case I had left something out. Also because I was 27 years old.

And because I had too many other things to cover. Guthrie’s image as a theatrical Johnny Appleseed suggests that Minneapolis was a cultural wasteland on his arrival. Hardly. I had listened to Minneapolis Symphony recordings as a teenager in Massachusetts—now I was reviewing them every Friday night at Northrop Auditorium. And there was more theatre around than I could keep up with. Guthrie’s Hamlet was my third visit to the play that season.

A further misconception: Regional theatre history—but let’s call it resident theatre—doesn’t begin with the Guthrie. It goes back more than a century—to the Provincetown Playhouse, the Pasadena Playhouse, the Cleveland Playhouse, Circle in the Square, Arena Stage of Washington (George Grizzard’s alma mater), the Federal Theatre Project from coast to coast; and, especially, to Margo Jones’s Theatre ’47 in Dallas, she being the most far-seeing pioneer of them all.

Here’s Jones in 1950: “I’d like to think that if I decided to take a cross-country trip in 1960, I could stop in every city with a population of 75,000 and see a good play well done.”

As Helen Sheehy notes in her fine biography, Margo, that pretty much describes what’s been achieved since Jones’s day. (Check out this TCG member theatre list, for instance.) The Guthrie is an important part in the story, but it was never the key log, nor should it be if you believe in the mantra of a decentralized American theatre, not marching to Broadway’s drumbeat or anybody else’s. I notice that the Guthrie now describes itself as “a national theatre center.” That’s reasonable.

What was orbiting around that center is perhaps the most remarkable thing—count the still-active American resident companies that share a founding date of 1963 or ’64, and thus a celebratory, half-century span: Washington’s Seattle Repertory Theatre, Rhode Island’s Trinity Repertory Company (begun as Repertory Theater in the Square), Connecticut’s Hartford Stage, Kansas City Repertory (earlier Missouri Repertory Theatre), California’s South Coast Repertory, Kentucky’s Actors Theatre of Louisville (begun as Actors, Inc.), the O’Neill Theater Center in Connecticut, Vermont’s Bread and Puppet Theater (see this story). Seminal barely begins to describe the moment (see also this roundup of 50th anniversary theatres).

But back to Minneapolis. Hamlet opened on May 9, an unseasonably warm evening, adding to generalized anxiety that made everybody feel a little less gala. “Even the audience had stage fright,” Guthrie notes in his memoir, A New Theatre.

Me too, of course, but I was counting on my Inner Journalist to see me through. It had already served me well. When I was officially barred from the Hamlet rehearsal room—nothing personal, but “it wouldn’t be fair to the actors”—I simply walked in and took a seat anyway, hoping that my clipboard would make me look official. “Thought you were the minister,” Guthrie said when I knew him better, not as amused as I thought he would be.

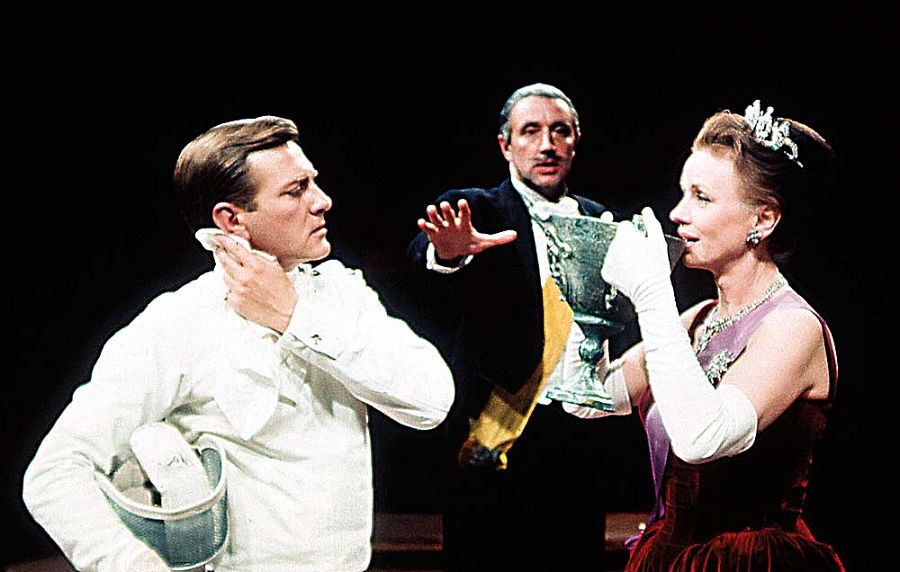

How was the show? Very long, almost four hours. I can only remember slices of it: Grizzard being literally shut out of the court after Claudius is through with him in Act 1 (very effective on the thrust stage); Jessica Tandy as Gertrude, trying to be sociable and queenly even though the game is up; Ken Ruta as the ghost of Hamlet’s father, an old Hessian general speaking from hell…

Every theatre critic in the Western world attended the opening, and we printed all the reviews next morning, including a rave from my idol, Walter Kerr, in the New York Times, and a pan from Acidy Cassidy, otherwise known as Claudia, in the Chicago Tribune.

My review (a qualified yes) struck me as timid but readable. It aroused no comment at the paper (that would be unprofessional), but Sage Cowles, the boss’s wife, came up to me the next evening in the Guthrie lobby just as we were going in to see Hume Cronyn’s masterful performance in The Miser.

“Oh, Dan,” she said. “We waited until the paper came out this morning to see what you’d say.” Remember this, I told myself. This is how it’s supposed to be.

And over the next 30 years, it usually was.

Dan Sullivan recently retired as director of O’Neill Theater Center’s National Critics Institute. He has reviewed for the Minneapolis Tribune, the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. He teaches at the University of Minnesota.