Last March we joined a delegation of 19 U.S theatre professionals on a one-week research program to Cuba, organized by Theatre Communications Group. We each had our own reasons for visiting Cuba. Some had specific theatre projects in mind that they needed to investigate. Some came from theatres in cities with substantial Cuban or Latino populations. All of us viewed the delegation as a one-of-a-kind introduction to contemporary Cuban performance. We needed to see firsthand how this economically poor country had remained so culturally rich.

We flew direct on a quick flight from Miami to Havana with research travel licenses granted by the U.S. government. Only one of our bags did not arrive, which somehow felt like a win for the group. Outside the airport was a colorful, hand-painted billboard featuring Che Guevara’s iconic image. We met our Cuban tour guide and boarded a bus that had been manufactured in China. Our plan was to head for the middle of the island and slowly work our way back, meeting with theatre companies and performing artists along the way.

On the bus, our guide gave us a succinct version of Cuban history. He talked openly about the transition of power from Batista to Castro, referring to the events of 1959 that secured Fidel Castro’s leadership as the “Triumph of the Revolution.” When we asked about the phrase, he casually told us it was synonymous with saying “1959,” after which socialist rule dominated Cuba. Private assets were nationalized. People’s homes and businesses suddenly belonged to the government, but in return education and healthcare became free. The beautiful historic homes and hotels in town squares, seen as symbols of bourgeois decadence, were left to crumble or were turned into state-run offices and apartment complexes. Citizens were employed and given a government salary, but today the average take-home pay is equivalent to a mere $20 a month.

In the 1990s, the fall of the Soviet Union devastated the Cuban economy. As a show of support for the island’s ideology, the USSR had kept Cuba’s economy afloat for decades. The Soviet collapse led to what our guide called the island’s “Special Period,” when rolling blackouts were common, resources were scarce, and reduced government rations meant widespread hunger and discontent. For a brief time private sector jobs were permitted, but entrepreneurship was cowed by steep taxes and a reliance on imported wholesale goods. Soviet-style housing complexes went up along empty roads far from the city centers. We asked our guide why the window shutters were all made of metal and learned it was because glass is expensive and difficult to replace.

In 2008, Fidel was succeeded by his brother, Raúl Castro, who has implemented significant changes. The atmosphere in Cuba now is one of transition, straddling old and new ways. For example, though cell phones have been in general use since 2007, public Internet access only began in June of this year—after our trip. At the steep price of roughly $5 per hour, as the Miami Herald has reported, few people can afford it. So our guide had an iPhone at the ready. But, like everyone else, he also carried his ration card to purchase limited amounts of subsidized goods, such as milk, eggs, meat and other daily necessities.

A significant gain toward financial stability came in 2009, when regulations stipulating that citizens could only earn one salary from a given ministry, or government department, were lifted. As we later learned from Cuba expert Arturo Lopez-Levy, of the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at University of Denver, these changes meant that hard-working citizens could suddenly hold two or more state-sanctioned positions in their field. This was the first of several large employment shifts, leading up to new allowances and diminished tax mandates for private sector jobs.

According to a 2011 article by Victoria Burnett in the New York Times, Raúl Castro had warned that “the state’s ‘inflated’ payrolls could end up ‘jeopardizing the very survival of the Revolution,’” if hundreds of thousands of people didn’t become self-employed as the country moved closer to a mixed economy. Today Cubans have the option to earn state-sanctioned salaries or to pave their own way in this new entrepreneurial territory. Granma, the Communist Party newspaper, dismissed any concerns that this might reflect a shift toward capitalism by writing, “The new tax system functions on the principle that those who earn more contribute more; this will help to increase sources of income for the government budget and achieve a suitable redistribution of income on the social scale.” Of course, several American sources hinted to us that these changes were really just a way to tax activity already taking place on the black market.

That black market for goods and services presumably exists because—while it is possible to live on the average $20 a month, due in part to ration cards, free healthcare and education, and minimal housing and utility costs—many Cuban families desire to supplement their total household incomes.

Interestingly, Cuba is one of the few places where artists (mostly visual artists and musicians) are among the wealthiest citizens. This is mainly owing to fewer travel restrictions for artists and because the U.S. embargo on Cuban goods—which forbade us from bringing back souvenir shot glasses or domino kits—does not stop U.S. citizens from purchasing Cuban art. Between the three of us, we helped a few screen-print artists quadruple the average monthly income. We visited the home of one successful visual artist, and it was the only time we were in the presence of what appeared to be wealth.

So what do all of these changes mean for the theatre companies we had gone there to meet? By the second day we were brimming with questions. If Cuba is a socialist country, then do actors really earn the same salary as doctors? Does the government get to censor their work?

We were eager to get some answers, but when we sat down with the company members of the first contemporary theatre we visited, it became clear that we’d prepared all the wrong questions. If you’ve ever attended a TCG conference, you know it’s perfectly acceptable to ask new colleagues about the size of their theatre’s operating budget, their percentage of contributed income or even their deficit! In Cuba those questions seemed preposterous. And, frankly, rude.

We were soon overwhelmed by the basics: Who determines a theatre company’s budget size or how many employees they can hire? Who pays the bills? Are there open casting calls? If everyone has to be assigned a job after graduating from school, where do all the acting students go? Do any of them wait tables?

The real mindbenders came later: How do Cuban citizens even afford theatre tickets? Does it matter if your theatre company has a flop? Who gets to keep the money if you have a hit? Can anyone start a theatre company? And most important: Why couldn’t we get any straight answers, regardless of whether we were speaking to an artist or an official?

Leaving aside the language barrier—and indeed, much of the correspondence and articles quoted here came to us via interpreters and translators—we had an incredibly difficult time wrapping our brains around this foreign system. We left Cuba with more questions than answers. And upon returning to the U.S., we kept trying to put the pieces together.

Our research led us to Eric Hershberg, director of the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies and professor of government at American University. We sent him a list of questions much like the ones above. His response was, “QUICK NOTE: These are very interesting research questions, and I’d be very interested to see the findings, but my sense is that it would require literally months, if not years, of painstaking research to generate data about which you could feel even modestly confident.” We had no choice but to laugh…and proceed anyway.

Thus, what you have here is not the final word from specialists in the field, but rather the account of how we came to better understand what we still didn’t know when we left Cuba. Our hope is to shed light on this subject and encourage others to explore it with us. In communicating with our Cuban colleagues, we have put together a basic primer of how they maintain the tradition of theatre with the extremely limited resources they receive.

With the exception of a small amateur movement, all theatre companies in Cuba today have been approved by the government and given a set number of “work positions,” or salaried staff members. These work positions generally include an artistic director, performers and various associated artists such as literary advisors, designers, publicists and producers. The smallest company that we visited had about 15 people and the largest employed closer to 80.

Most of the companies we met were created or expanded through a government program called the Project Policy of 1986, which allowed groups of aspiring theatremakers to petition Cuba’s National Council of Performance Arts (Consejo Nacional de las Artes Escenicas or CNAE), a division of the Ministry of Culture, for official status and be granted salaried work positions. But it is not easy to create a project. For example, when esteemed director Carlos Celdrán started Argos Teatro in 1996, the actors who joined him in this new venture went unpaid for almost four years before receiving CNAE’s stamp of approval.

A high-level Cuban official at one of the major arts foundations we visited pointed out that the initial impulse behind the Project Policy was to create a system that would reevaluate the artistic merit and social value of existing companies every few years—the implication being that unworthy companies might be in jeopardy of losing their status. This official was of the opinion that, in reality, these companies are supported in perpetuity, regardless of quality, from a fixed budget that now has little room for younger artists to form new groups. This was a particularly interesting observation given that President Castro recently announced the regular evaluation of larger state-funded companies for efficiency and quality, implying that underperforming companies would be closed or downsized. A Reuters article by Marc Frank indicated this past July, however, that the Cuban and foreign press remain highly skeptical of the credibility of these threats.

Teresa Subiaut Sánchez, an international relations specialist with CNAE, confirmed for us that the “Cuban government lends its support through the Ministry of Culture in its educational policies and attention to the population’s cultural development.” This funding goes toward government salaries, restoration of theatres that were left to deteriorate or were devastated by hurricanes, as well as “other investments,” which include scenic, prop and costume design enhancements. Each company recognized by CNAE receives support. It almost takes your breath away when Subiaut Sánchez simply states, “All artists and technical staff are always guaranteed a basic salary.” We were also pleasantly surprised to learn from Joel Sáez, artistic director of Estudio Teatral de Santa Clara, that despite being fully supported by government funds, “The state and its institutions don’t interfere [with] the topics or the plays” that these troupes produce.

With so much clamoring in the U.S. for government funding for the arts, the Cuban model appears almost utopian. But as lighting designer Manolo Garriga of Argos Teatro later told us, “All the cultural institutions, theatres, art schools, theatre companies, etc., can only be subsidized by the government.” It is the emphasis on “can only” that seemed problematic to us. Cubans are paid by the government in Cuban Pesos (CUP). At the time this article was written, there were about 26 CUP to 1 USD. According to Garriga, the salary for an experienced actor is between 640 and 650 CUP per month, or around $25. A director might receive an additional 50 to 100 CUP. Technicians, or designers, receive anywhere from 250 to 400 CUP. Since the early ’90s, these salaries have remained the primary means of assistance offered by CNAE. Joel Sáez further explained that “each province of the country receives a budget for its groups, [and] that budget is divided equitably” among all the theatre companies, taking into account the varying sizes of these organizations. Their salary budgets are simply an aggregate of what each member in the group receives, and salaries are paid directly by CNAE’s provincial divisions, rather than by the groups themselves.

Regardless of company size, each theatre also has a contract with the National Council stating how long they will rehearse on salary and when they will open and close each production. Many companies produce only one or two shows a year, rehearsing up to five months for a single production. Theatre administrators are in charge of reporting everything from the number of performances to the amount of tickets sold, as well as depositing earned income with CNAE. In the case of Estudio Teatral, Sáez says they are committed to approximately 40 performances a year. Though they are supposed to meet the agreed-upon terms, if for some reason they are unable to do so, “the solution is never [a] salary or funding suspension.”

In addition to salaries, CNAE also provides each theatre company a budget for annual production needs. Estudio Teatral shared with us that their annual government production budget is around 10,000 CUP, or $385, with about 60 percent going to authors’ rights and the remaining 40 percent going toward production values. For additional production support, theatre companies can present projects to CNAE and request materials, as well as labor. The idea is that a company submits its artistic production needs, and the items—costumes, sets, props—are constructed in a state workshop. This method takes a long time, and according to Sáez, “There is a tremendous shortage of material resources, and there are many professional groups.” He notes, “There is a state will for helping but there are not resources.”

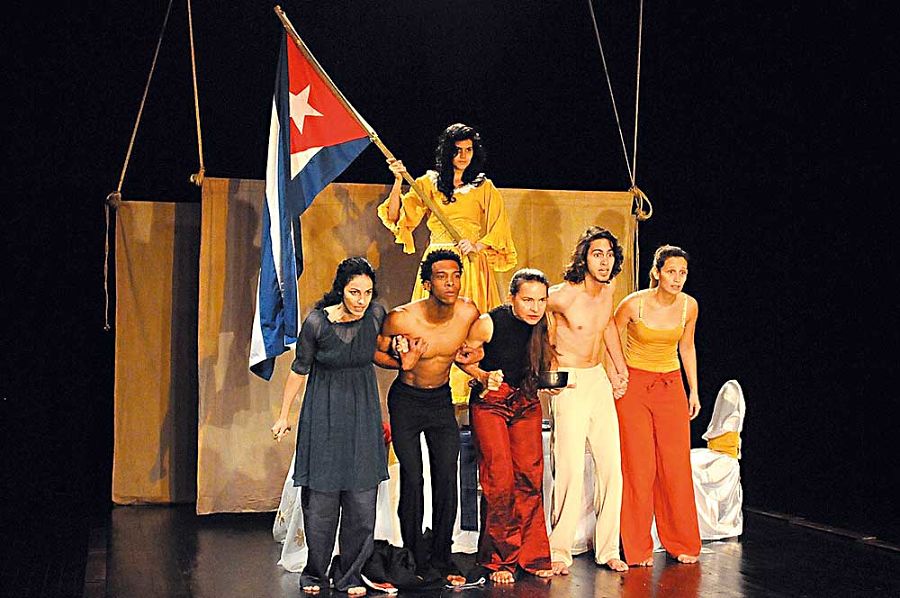

To compensate, companies have decreased their production needs and sought aesthetics that are more poetic than literal. “The wealth of our performances doesn’t rest in technical or material aspects, but in the capacity to go deep into the human universe of our time within the context of a poor reality; poor in resources, but rich in creativity,” said Roxana Pineda, a founder of Estudio Teatral. But Sáez added that, many times, “We have paid [out] of our pocket or we have been helped by friends that live abroad.”

It is worth noting that recent Obama administration policy changes have significantly lifted restrictions on the amount of money Cuban-Americans can send to family members on the island, and that as of 2012 cash remittances—according to Emilio Morales and Joseph L. Scarpaci of Miami’s Havana Consulting Group, in a post on Arch Ritter’s Cuban Economy Blog—“outweigh government salaries by 3 to 1.”

Other funding can also come from foreign embassies in Cuba that support work relating to the cultural influence of their homelands. Thus, theatre companies are sometimes able to get enough money to buy costumes and props outright, rather than having to wait for the state workshops to make them. Of course, we later learned from a U.S. source that the ability to sell such items on the black market may be a hidden benefit to this alternate process.

Ticket prices range from 2 CUP (or 10 cents) in Santa Clara, with students and disabled patrons paying half price, to 5 or even 10 CUP in Havana, depending on the venue and the quality of the production. To fill the seats, companies approach their contacts at newspapers and radio and TV stations, looking for interview and promotional opportunities during peak hours. Argos Teatro’s leaders say they pay for posters, but they are able to get playbills through CNAE, which also has an advertising office. This state office can pay for posters too, but most companies prefer more expedient solutions, like approaching embassies and institutions for support in the form of printing services.

Banners, billboards and other large-scale advertising, so present in the U.S., are completely absent in Cuba, where the only billboards we saw contained slogans and imagery celebrating the Triumph of the Revolution.

A direct benefit of the 2009 reforms allowing workers to draw multiple salaries in their field is that actors lucky enough to get the work can also make one or two films a year or act on TV, as long as the time commitment doesn’t conflict with their state-sanctioned employment at the theatre company. For the companies we visited, this also means their publicists can earn second salaries as their production managers and take home wages more comparable to those of private entrepreneurs. Garriga of Argos Teatro wrote to us, “Since we do whatever is necessary, no matter if you are the sound man, or the lighting man, there is no [conflict] at all…the most important thing is that we develop a feeling of belonging in every person that is part of the company.” He added, “Of course this is our formula. In bigger companies or venues, each person has a job, and he wouldn’t like to do what is not in his profile.”

Being a theatre artist in any country, even with a guaranteed salary, requires consistent sacrifices. Several sources confirmed that unlike jobs in grocery stores or hotels, being an actor in Cuba leaves you with no possibility of acquiring things to hawk on the black market. We also learned that, just like in the U.S., most theatre professionals must teach to make ends meet. Cubans were able to do this even before the 2009 changes because their teaching salaries came from the Ministry of Higher Education and did not detract from their theatre salaries, which came from the Ministry of Culture.

As for whether Cuban actors can now be waiters on the side, or tutors, or street performers who dress up as historical characters for tourists—which according to Granma are all on the shortlist of about 180 jobs recently privatized—the answer is unclear. According to writer and arts critic Amado del Pino, “Many actors and other theatre workers supplement inadequate government salaries with work in fields expected to take off under the new circumstances. There was a fleeting and unfinished initiative to pay [actors] per performance, but except for that, we’re left with an unfortunate paradox: Since everyone is on salary, those who work less have more opportunity to earn additional pay in other sectors while still receiving their monthly salary, whether or not they are working in the theatre.” In other words, until the Ministry of Culture takes a performer off its payroll, these artists make more money by turning down roles to pursue other work, while still collecting their state salary.

Though Cuba is an incredible place to be a young actor, we should mention that most aspiring thespians are weeded out early on, as there are very few available slots in the free university-level acting programs. However, young performers who can compete at this level do get to spend two years with a professional theatre as paid apprentices. This postgraduate time in Cuba, called “Social Service,” is mandatory, but not everyone has such a dream job. Our tour guide, for instance, told us that he spent his Social Service years manning a prison tower with an AK-47.

While many restrictions to private enterprise have been or are in the process of being lifted, theatre artists must still be careful not to lean into capitalist tendencies. Last year, a Reuters article led to the near-immediate closing of one of Cuba’s largest cabarets, El Cabildo. In the article, journalist Marc Frank profiled the cabaret’s owner, Ulises Aquino, an opera singer who took advantage of the newly legitimized private business sector to open a permanent home for his group, Opera de la Calle (Opera of the Street). Frank wrote that the restrictions to private initiatives are meant to “ensure that Cuba does not return to a society of haves and have nots. Aquino mixes individual initiative with community activism, hosting free children’s activities weekend mornings and keeping his prices affordable.” Aquino was implementing many mission-based programs, like the ones we see at U.S. nonprofit theatres across the country, and staying within the mores of the socialist state.

Frank’s article, however, also referenced Aquino’s “moxie,” noting that while private restaurants can only seat 50 people, Aquino secured and paid for three restaurant licenses to create seating for 150. The article ran on a Wednesday. By the following Monday, as reported in a Global Post article by Nick Miroff titled “When Bureaucrats Attack,” local officials had raided the club and shut it down indefinitely. Though Aquino was, as Miroff put it, “a good socialist businessman,” the message was clear.

Perhaps this was why when we prodded our guide with questions, he prefaced his answers by jokingly asking if we were spies. We knew he was just playing at stereotypes, but while we were in Cuba, the pervasive feeling that whatever you built for yourself could be taken from you was overwhelming.

Though these recent economic changes still feel tenuous and difficult to navigate, they are part of a larger tapestry of policy shifts in Cuba and the U.S. that offers increasing access and cultural exchange. New “people-to-people” licenses being issued to U.S. citizens, Cuba’s decision to forgo exit visas for islanders traveling abroad, and relaxed restrictions within the LORT/AEA collective bargaining agreement should make it easier for U.S. theatres to employ Non-Resident Alien companies and introduce our audiences to Cuban contemporary performance. At the close of her e-mail correspondence, Subiaut Sánchez wrote to us, “I know that it’s NOT your fault…but I feel I need to tell you—and you saw for your[selves] when you visited Cuba—that the political and economic sanctions that the United States has imposed on us for the past 50 years have had a significant effect on us. Nevertheless, we continue creating ART.”

It is our hope that more U.S. theatre producers will help us share this great “ART” and the cultural wealth we witnessed during our trip.

Diana Buirski serves as the general manager of Off-Center @ The Jones, a division of the Denver Center Theatre Company in Colorado. Erica Nagel is the director of education and engagement at McCarter Theatre Center in New Jersey. Meghan Pressman is the director of development at Signature Theatre in New York City. Support for their travel to Cuba and research for this article was made possible by their supplemental travel funds as participants in TCG’s Leadership U: One-on-One and New Generations: Future Leaders programs.

The authors would like to thank L.A.-based multidisciplinary artist Sage Lewis, who organized their itinerary in Cuba and connected them with numerous Cuban artists and agencies. Special thanks also to Alejandro Marrero and Tania Cordero for their assistance in reaching Spanish-speaking sources. The names of several sources who wished to remain anonymous have been omitted.