In addition to his work in film and television, Stacy Keach’s distinguished stage career spans the last 50 years and includes performances at the Public Theater/New York Shakespeare Festival, the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, Lincoln Center Theater, Yale Repertory Theatre, Chicago’s Goodman Theatre and D.C.’s Shakespeare Theatre Company. In his memoir All in All, out this month, he shares hard-won insights into some of Shakespeare’s most complex characters. And at Shakespeare Theatre Company this coming March, Keach will play Falstaff in Henry IV, a role he last tackled in Central Park in 1968. —The Editors

Falstaff

Falstaff, when performed in both Henrys together, is an enormous undertaking. Part 2 is particularly filled with long speeches—Falstaff does tend to go on—and this reinforces my point about learning as many of your lines as possible before rehearsals even begin.

I’ve always thought of Falstaff as a potent mix of comedy and tragedy, intersecting his desperate need for the love and attention of young Prince Hal. Some of that is genuine, and some is driven by his notion of being a privileged member of the future king’s court. The showmanship comes easily, but finding that emotional state hidden beneath the bravado is the challenge. I try delivering Falstaff’s bluster with a touch of self-awareness—he knows he is full of it, that he is endlessly embellishing when he shouldn’t, yet being aware of his own flaws doesn’t change the nature of his behavior.

We see this clearly in the story he tells of the robbery, which he expands and exaggerates as he goes, pushing forward even as each false step is exposed. The telling always earns big laughs, which is a challenge for an actor trying to maintain his rhythm and pace, but it’s also a challenge to not lose sight of the pathos beneath the humor in Shakespeare’s writing.

I also want to explore a side of Falstaff that I didn’t see clearly my first time around. I want to capture the sense that Falstaff subconsciously knows what is coming: Shakespeare brilliantly presages the moment he is banished in the scene where Falstaff and Hal are playing a game in which Falstaff acts at being Hal and Hal plays his father, Henry, the king. Falstaff naturally plays this for laughs, saying:

No, my good lord; banish Peto, banish Bardolph, banish Poins; but for sweet Jack Falstaff, kind Jack Falstaff, true Jack Falstaff, valiant Jack Falstaff, and therefore more valiant, being, as he is, old Jack Falstaff, banish not him thy Harry’s company: banish not him thy Harry’s company: banish plump Jack, and banish all the world.

It’s a tricky scene, since he’s making a plea to Hal, yet he is unwilling to believe that this is what fate holds in store for him, even if the king should turn against him. Again, Falstaff will charm the audience and get the laughs, yet the actor must reveal how he is clinging to his belief that he will be saved and cherished by Hal. To accomplish this Falstaff must really buy into the idea that this is all a game, that none of this will come to pass. And I can only do that if, in that moment, I allow the slightest shadow of doubt to creep into my mind.

Hamlet

Falstaff, like Richard III or Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is great fun to play. Hamlet is more like King Lear—undeniably rewarding but more of a challenge. The early part of the play is especially tough sledding. Every actor who plays Hamlet confronts that most awkward of moments, where you reach a part in the play where the entire audience is waiting to hear how you deliver a certain line—a line they’ve known by heart since they were children, probably since before they knew who Hamlet was.

To be, or not to be, that is the question…

It doesn’t matter if the audience knows it is coming. The only way to make the line work is as if the thought of suicide is just occurring to you for the first time in that particular moment. That need to act as if each line is a fresh thought each night is true of all acting, of course, but it is more of a challenge when the audience knows what you are going to say and when it is a soliloquy—moment-to-moment acting is easier when you’re responding to another performer, since the slightest variation in his or her delivery alters your response each time out.

The only way to feel truly spontaneous, as I tell my students, is to take chances, to risk making a fool of yourself. This is one reason I do acting exercises with them where they make nonsense sounds, first as a 5-year-old, then as a 95-year-old. It harkens back to what Hugh Cruttwell taught me at LAMDA, when he criticized my Brutus for being too well spoken, too well thought out. You need that as a foundation from which you can depart—your first obligation as an actor is to be seen and to be heard, but depart you must, into an unpredictable place, free of preconceptions.

One night you might feel tentative and say, “To be” and then pause and then in a questioning way add “or not to be.” The next night perhaps you’re more confident and you snarl the line with a touch of sarcasm. The changes can be minute, but they are important—and that first line informs how you deliver the next.

There are so many ways to interpret Shakespeare, if you’re willing to take risks. I was tired of seeing Hamlet as neurotic and indecisive, paralyzed by thought. I thought the text supported playing him as someone making too many decisions, making active choices, but racing from one to another, driven by his nervous energy. I realized in rehearsal that while I could literally run across the stage during Hamlet’s first soliloquy, I could show that his thoughts and feelings were skittering from one place to the next without physically moving.

I also would argue that Hamlet can seem angry and frustrated in his first soliloquy, but he can’t yet seem to be “mad” or “crazy.” I found that this quality doesn’t really come to light until he sees the Ghost.

Again, Hamlet is not timid in his scene with the Ghost; when he cries, “Oh, Vengeance,” he must mean it. One of the most difficult scenes is when Hamlet comes up with a sword behind Claudius when he’s praying, with the full intention of killing him. If Hamlet is weak from the beginning, then we expect him to be unable to execute and the scene is devoid of dramatic tension. But if Hamlet is strong, a man of action, then when he hesitates and ponders the consequences of his action, it creates a tension that gives us a further insight into his character. (In my own mind, trying to be Hamlet born anew each night, I went out thinking each time that I was going to kill him.) An active Hamlet also makes more sense at the end of the play, where it would otherwise seem jarring that he is a great swordsman in his duel with Laertes.

There are other actors who have also pushed themselves to find new life in this centuries-old play. When I saw Jonathan Pryce play Hamlet and do the Ghost as well (in a different voice), as if it were not an actual apparition but Hamlet’s inner demons tormenting him, all I could think was, “I wish I’d done that.”

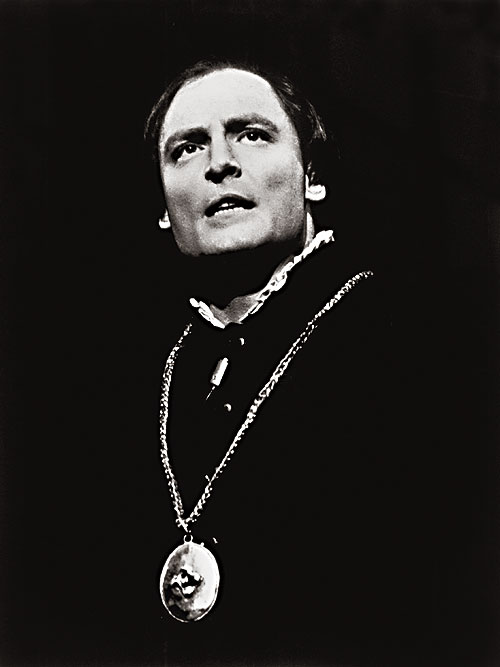

Richard III

In the Hospital for Overacting, there is a special ward devoted to Richard III, with actors in costume shrieking, “A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!”

There is no such hospital—it exists only in a sketch from “Monty Python’s Flying Circus“—but it points to one of the tricks to playing Richard.

Richard is, by his very nature, a scenery chewer, and you can’t hold back in the role—underplay him and you deprive him of the snake-like charm that enables him to slither his way onto the throne. Yet many actors go too far, and, I confess, there were nights when I did so myself. I’ve seen actors interrupt the line “That dogs bark at me, as I halt by them,” by howling and barking. It felt contrived and unnecessary, trying to elicit cheap laughs from the audience. That section of Richard’s first soliloquy—“Deform’d, unfinish’d, sent before my time / Into this breathing world, scarce half made up”—needs to express Richard’s hurt and anger. It’s part of the balance an actor must find with Richard. The script gives you license to ham it up, but you have to earn it by showing how deeply committed Richard is to alleviating the pain inside him. His actions are dressed in a lust for power and desire for vengeance, but that inner hurt is real—he has been rejected by society, and he needs to be able to look at himself with respect—and it enables audiences to feel for Richard even as they find him scary. The audience must always think Richard is dangerous, and not just entertaining.

Make it personal. I say it over and over but it’s true—if you make it personal, it’s difficult to overact. For me, I drew on how I was teased as a kid because of my cleft lip, but everyone has felt like an outsider or endured the sting of rejection.

As for that infamous horse, it again comes down to existing in the moment. Richard says “A horse, a horse.” The first time—if you were saying this as if it were really the first and only time—it is an act of discovery. Look around and realize that your troops are gone, your horse is gone, all your power and your means of defense are gone. You are playing an action. The second one can be more of a cry for help as can the shout of “My kingdom for a horse,” though that can also be played as I did it—Richard is down and he is desperate but he believes that if he could just get one thing to latch onto he’d figure out a way to survive. After all, that is the story of his entire life and his rise to power. This time, however, his options have finally run out.

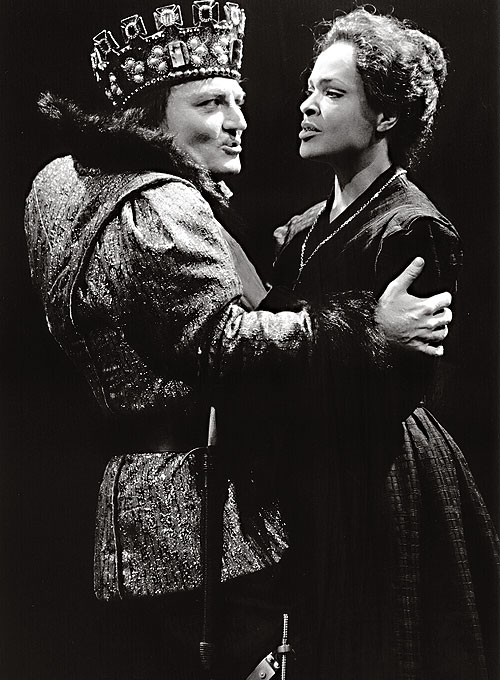

Macbeth

It is difficult for an audience to relate to a murderer, especially one who has just killed his king, a good man who had trusted and promoted him. To create any relationship between Macbeth and the audience, the actor must show his vulnerability, his sense of remorse, and an understanding of what he has done and what he has lost.

We opened our production with a battle scene. Though Shakespeare wrote it as exposition, it is more exciting to see it onstage, and it introduces Macbeth as a great swordsman and courageous warrior, a genuine hero, which will make his fall more tragic.

We begin to see the more human side of Macbeth after he kills Duncan, especially when Banquo’s ghost appears—if you capture his guilt and vulnerability there, right as he is cracking up, then the play takes on another dimension that moves it beyond the action and ideas. It’s dangerous for the actor to play for sympathy, however, since he really doesn’t deserve it.

I wish Shakespeare had written a scene at the end in which Macbeth interacts with Lady Macbeth in her chamber after she has gone mad and before she dies. It would have helped us see another side of his character. Since he doesn’t, the actor must remember that one of Shakespeare’s most challenging soliloquies—“Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow / Creeps in this petty pace from day to day”—actually starts with the line, “She should have died hereafter.” Many actors forget that and depersonalize this speech; the bleak nihilism of the “sound and fury / Signifying nothing” tempts them into making this a grand statement about the world itself, but it can only become that if one remembers to start by connecting it to Macbeth’s loss, the death of the woman he loved, the pain and cost of this journey they started together.

King Lear

Sir John Gielgud was once asked the key to a great King Lear. “Make sure you have a light Cordelia,” he deadpanned.

Yes, it’s funny, but there’s a truth to that pragmatism—much of theatre is about executing blocking in a way that seems effortless and natural, which isn’t easy when you’re trying to carry Cordelia’s limp body onstage. (My Cordelia, Laura Odeh, is a marvelous actress and eminently carry-able, if that were a word.)

There are probably as many ways to play Lear as there are lines to memorize.

In my opening scene, I came out exuberant, dancing and celebrating. This was no aged feeble leader. As with Hamlet or Macbeth, I’m not in favor of playing Lear as completely daft from the beginning—it must be a journey as his guilty conscience eats at him and forces him to retreat from a world he no longer understands. As with the other roles I’ve discussed, I wanted to create an arc, a progression for my character, and my Lear had farther to fall when he, fueled by years of egocentricity and self-absorption, convinces himself that Cordelia has betrayed him. I did foreshadow what was to come, however, with a sudden, “Oh,” and a clutch of my heart. I’m okay, but I need to sit now, for a moment, to catch my breath. Later, when Lear is screaming at Goneril and Regan, he again has a minor heart incident. The stage is set, so to speak, for his death, when he is grieving for poor Cordelia, and is ready to go, he no longer has any reason for his heart to continue beating.

“Look there,” Shakespeare writes and he repeats the phrase. I played it as if I was seeing Cordelia’s spirit leave her body and ascend to heaven, leaning back to watch her go. Then my heart gave out and I fell back dead in Kent’s arms. The dead fall is as pure a risk as there is onstage and requires complete trust in your fellow actor. Fortunately, my Kent, Steve Pickering (who also appeared in more than 700 performances of Robert Falls’s staging of Death of a Salesman), caught me every time.

The most famous scene in King Lear is one that often drives actors nuts and leaves them hoarse. The idea of Lear raging against the storm is taken too literally, with crashing thunder that forces actors to bellow in order to be heard. Such competition between man and nature is counterproductive to the show, not to mention the actor’s voice. Lear’s last line in the scene with Goneril and Regan is “Oh fool, I shall go mad,” so when we next encounter him in the storm with the Fool (brilliantly played by Howard Witt in my two productions), Lear has lost his mind and is a child again, embracing the storm, happy to be challenging Nature and singing in the rain. A little thunder goes a long way, and it’s best when underplayed—the storm is inside Lear’s head, where he is struggling to grasp what has befallen him and what he has done.

The role and the play are extremely complex, and I believe it’s always good to understand it in context of Shakespeare’s work and of past productions. I researched where Shakespeare drew his story from, studying Plutarch’s Lives and Holinshed’s Chronicles, trying to understand how the pagan culture and Christian overtones of forgiveness and redemption mingled. I watched Olivier’s and Ian Holm’s movie versions of King Lear, and I recalled Lee Cobb’s interpretation in the Lincoln Center production where I played Edmund years ago. I wanted all of my research to enhance a more detailed performance, but this was orchestrated well in advance of the first preview, so that when I got out onstage, I could throw it all away and just deal with the text, and be in the moment with my fellow actors in a world we were creating anew in each moment, each performance.

This essay was excerpted from the book All in All by Stacy Keach, copyright 2013 by Stacy Keach. Used by permission of the Lyons Press.