Lyndon Baines Johnson was a proud son of Texas and a born storyteller. His colorful, often profane, sometimes apocryphal yarns and anecdotes were part and parcel of his folksy charm—and his genius for political persuasion. Robert Schenkkan, another two-fisted storyteller from Texas, has spun big tales for stage and screen from the annals of Kentucky, the backwoods of the southern Bible Belt, the plains of Lakota country and America’s World War II outposts in the Pacific. Now he is drawing on a multitude of private and public yarns to create one of his most challenging works yet: a theatrical portrait of the presidential life and times of LBJ—a vivid, stubbornly contradictory former titan whose six-year tenure as 36th President of the United States began and ended tragically, but was marked by momentous, lasting accomplishments.

Despite his tremendous impact on U.S. foreign and domestic policies over the last half-century, Johnson has been all but absent from mainstream drama since a grotesque cartoon of him ran amok in Barbara Garson’s 1967 antiwar play, MacBird! He’s long since been eclipsed in popular-culture discourse by two other presidents of his time, John F. Kennedy (whom he abruptly succeeded, following the latter’s 1963 assassination) and Richard M. Nixon. For Schenkkan, one play was not enough for a warts-and-all portrayal of the multifaceted man who one of America’s most consequential and controversial leaders. “Johnson was, in a way, all things to all people,” he reflects. “But who was he really? What did he really want?”

To address those questions, he expanded his intimate yet epic chronicle covering LBJ’S White House tenure from a single drama into two stand-alone yet interconnected plays.

The first, All The Way, was commissioned by Oregon Shakespeare Festival as part of the Ashland, Ore., company’s American Revolutions cycle of U.S. history dramas. It centers on LBJ’s complex backstage machinations to pass one of his greatest legacies: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which effectively ended centuries of racial segregation in America. The late President’s well-documented crudeness, his paranoid streak, his competitiveness and ruthlessness in pursuing his goals are well in evidence in All the Way, as Johnson works the phones, plots his reelection campaign and skillfully endeavors to manipulate leading legislators, civil rights leaders and the voting public.

But that’s one side of the coin: LBJ’s masterful and genuine rapport with people, his sly and colorful wit, and his warmth with those closest to him, not to mention his granite-solid convictions about eradicating poverty and racism in American society, come through just as clearly.

“Johnson was such an extraordinary figure, so complicated and ultimately tragic,” says Schenkkan. “He was a man who did an incredible amount of good for this country—and then came Vietnam. Then the lying started, and it never stopped.”

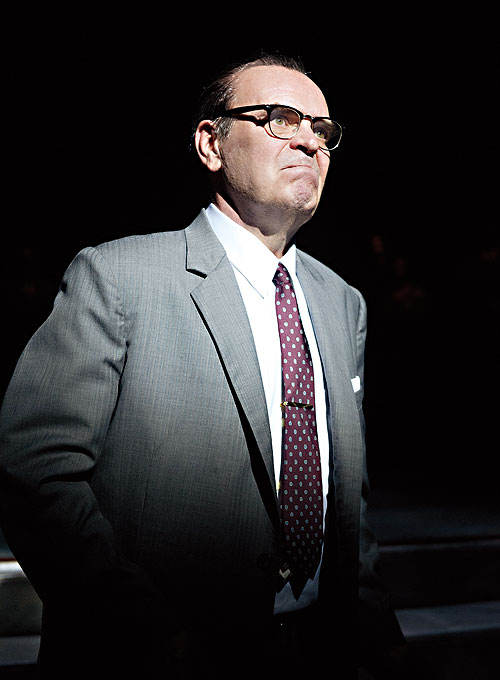

ALL THE WAY PREMIERED TO POSITIVE REVIEWS IN ASHLAND IN 2012, with Jack Willis as the president; a second staging guided by the same director, OSF artistic head Bill Rauch, is currently running at American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., through Oct. 12. It stars Bryan Cranston, the Emmy-honored star of TV’s “Breaking Bad,” in the demanding lead role.

Schenkkan is now completing the play’s sequel, The Great Society. The second script covers a period of additional legislative milestones achieved by Johnson (the creation of Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, the food stamp program, the Voting Rights and Fair Housing acts, et al.)—as well as his escalation of the U.S. war in Vietnam and the dire consequences of that military adventure. Commissioned by Seattle Repertory Theatre, The Great Society is set to debut at OSF in the summer of 2014.

All the Way has already garnered two major honors (the new Edward M. Kennedy Prize for drama inspired by American history, and the ATCA/Steinberg New American Play Award). Rumors of a Broadway production are flying (along with reports that it may face a competing LBJ play by Alexander Harrington, also titled The Great Society).

But it is daring (some might say foolhardy) for any contemporary American playwright to conjure a theatrical panorama that, in total, runs roughly six hours, and requires a 17-actor ensemble to play more than 50 roles. Schenkkan says he’s grateful there are regional theatres like OSF, ART and Seattle Rep that will tackle such an undertaking.

“I’m a big believer that stories have to be the length they need to be,” Schenkkan states in an extended conversation at his Seattle home overlooking Lake Washington. And he expresses no doubt that his latest subject deserves a long gaze: “This just happened to be what the story required.” Let it not be forgotten that Schenkkan is, after all, the author of the wildly ambitious, nine-part stage epic The Kentucky Cycle—which encompasses 200 years of state history in more than six hours, and which earned him a 1992 Pulitzer.

As for his several years of commitment to the LBJ project, and its potential value to audiences, the playwright quotes leading Johnson biographer Robert Caro: “America can’t fully understand its history without knowing Lyndon Baines Johnson.”

“We’re beginning to revisit LBJ’s legacy because of current events,” observes Schenkkan. “That’s a healthy thing. These days we have congressional gridlock. And what was it that LBJ signed into law in his first few years as president? Medicare, civil rights, voting rights…. It’s an amazing achievement.

“I wanted people to see the sausage-making of politics, what it really took to get these things through against fierce opposition, and how some of them, like the 1965 Voting Rights Act, are threatened today. The sausage-making is an ugly thing, but Johnson didn’t blanch at it. I think he loved it.”

Schenkkan also wanted to explore—as Tony Kushner recently did in his Lincoln screenplay—the human dimensions of leadership, and the personality of a man utterly driven by and confident in his ability to effect change, despite the price it exacted in his own life, and his nation’s.

“I’m interested in the whole notion of power and morality, means and end,” says Schenkkan, who has long been concerned with the moral dilemmas of powerful individuals. “And I think this story is extraordinarily relevant today. I think Americans are hungry for this kind of dialectic and dialogue.”