Sometimes, it seems, the two heavyweights are getting ready to rumble.

In one corner is Charleston, S.C.–born and Harlem-reared playwright Carlyle Brown. In the other, representing the Gateway Arch, is St. Louis–bred actor-director James A. Williams. The two have been coming to blows since 1986, when they met in the Twin Cities before the premiere of Brown’s breakout play, The Little Tommy Parker Celebrated Colored Minstrel Show. Williams originated Brown’s critical gloss on the iconic minstrelsy character Tambo in Tommy Parker.

“If people don’t know us, and we’re in a room talking, it might sound like we’re fighting,” says Williams, whom the Minneapolis Star Tribune named its artist of the year in 2008 for his magisterial turns in August Wilson’s plays. “It’s a very passionate exchange of ideas.”

“Our conversations and arguments are above a certain baseline,” says Brown, whose plays include Pure Confidence and The African Company Presents Richard III. “When you work with the same people all the time, you don’t have to explain yourself. The problem with explanation is that the more explicative you become, the further away you get from your art. We get right to the heart of things.”

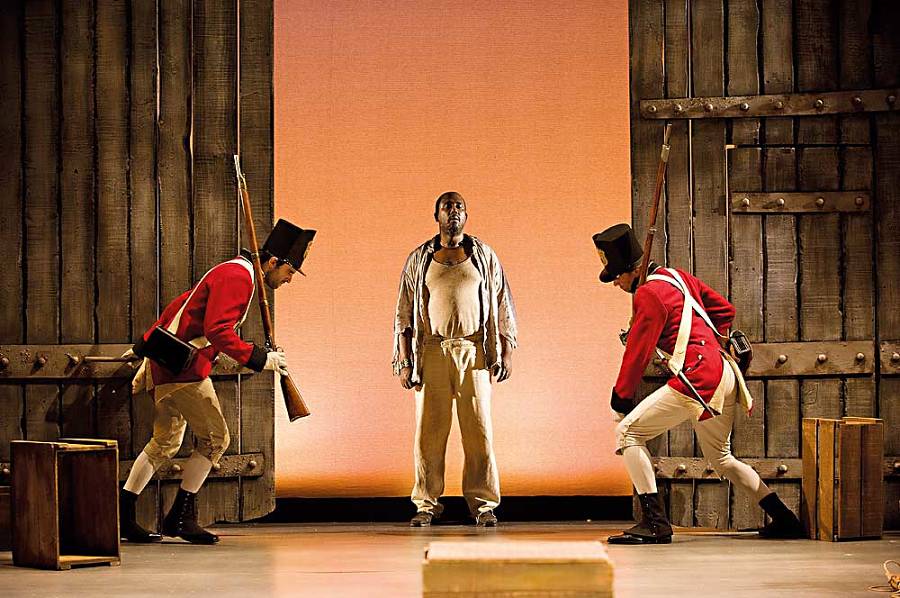

In the 27 years since they started working together, Brown has written more than half-a-dozen parts for Williams. The actor depicted King Dick in Brown’s Dartmoor Prison. He has played all the famous black actors to portray Othello in The Masks of Othello: A Theatrical Essay, a piece gleaned from critical reviews over the centuries. And he will play Uncle Tom in Abe Lincoln and Uncle Tom in the White House, which opens in March 2014 at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis under the aegis of Brown’s eponymous company. Williams will portray the fictive character come to life from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s classic novel.

Williams also has directed a production of Tommy Parker at Missouri’s St. Louis Black Repertory, while Brown has served as dramaturg for an Othello in which Williams played the Moor.

Over coffee and pastries at a Twin Cities café, not far from where both men live, the pair seem like old-marrieds, with the years etched in their grizzled faces and salt sprinkled liberally in the pepper of their hair. The sparring partners laugh heartily and smile with approval at each other as they explain that their decades-long friendship and professional relationship are similarly grounded in a shared passion about the transformative power of theatre, as well as profound mutual respect and a kinship based on biographies of similar struggles and triumphs.

Before he became an actor and director, Williams, who also works with at-risk young men ensnared in the criminal justice system, says that he did not even dream of a life of theatre. “Growing up in St. Louis, the thing I wanted to be was not shot,” ventures Williams. “Theatre was and is a personal salvation for me.”

Williams went to Macalester College in St. Paul, and launched his career as an early member of that city’s Penumbra Theatre, the place where August Wilson received his first professional production and which, arguably, remains the best interpreter of Wilson’s canon. (Williams is called “Jay Dub” by his friends, including the late Wilson, who named a character in Jitney “Doub” in Williams’s honor.)

Before Brown became a playwright, he had gone through the heady days of the civil rights struggle and become a ship captain. As he plied the seas, he sorted ideas, scenarios and dialogue in his head. Tommy Parker, which premiered in 1987 under Lou Bellamy’s direction at Penumbra, was his first produced play. Williams had been on the new-play committee that selected it.

“I remember, when we were reading it, we all went wow,” says Williams. “It jumped off the page. It was poignant with the history of performers and minstrelsy and the struggle to be a man.”

That play announced Brown’s interests as a playwright. He interrogates history, writing characters who are not flights of fancy in historical pageants, not absurdities.

“A play is a struggle for power,” says Brown. “You can’t give the agency to one set of characters or actors. Black people can’t be spectators in their own stories set in slavery, or the civil rights era, or wherever.”

Williams played a variety of male parts in Talking Masks, Brown’s collection of six playlets—one of the shorts, The Runaway Honeymoon, is based on a true story of an enslaved couple that escaped to freedom because the wife, who was fair-skinned, posed as a man. The husband, in turn, posed as her slave. “One of the beautiful things about working with a great playwright is that the words sometimes walk with you into the world,” says Williams.

Brown’s Dartmoor Prison, for example, is set in 1812. Its historical facts are not broadly known. The War of 1812 began in part because the British navy was impressing American seamen into service for its war against Napoleon. Those Americans who refused to fight were imprisoned on a British moor, including a significant proportion of black sailors. Inside the prison, as depicted in Brown’s play, the sailors self-segregate and are in a constant state of battle.

Brown and Williams share similar ideas about how they build their characters. “When I’m working, I stack ideas on top of each other, like bricks or pancakes,” explains Williams. “If he gives me something that doesn’t stack, that sits akimbo, then I need him to explain it to me so that we can try to build the character.”

The two men use the issue of colorblind casting to illustrate their point. “When people start talking about colorblind casting, they’re talking about something we know doesn’t exist, because the moment you walk out onstage, folks go, ‘Oh, it’s so nice they let the maid sit at the table with the family,’” says Williams.

Working with Brown, Williams says, allows him to bring his own experiences and ideas to the play as opposed to “living in a world that’s a flight of fancy. It’s doing a play rather than doing a quote-unquote diverse play.”

For Brown, historical plays get at the heart of his mission. “Over time, you talk to [black] actors who go to conservatories—be it Yale, Juilliard, whatever,” says Brown. “It’s certainly not intentional, but they’re asked to leave the core parts of their being at the door. They’re doing European plays about European ideas—roles where they can’t bring the full energy of their inner beings and intellectual outlooks on the characters. I figured, if I was going to be a playwright, which doesn’t make any money, I’d do it in the service of something. And that is to create roles for actors—black actors.”

Rohan Preston is the theatre critic for the Minneapolis Star Tribune.