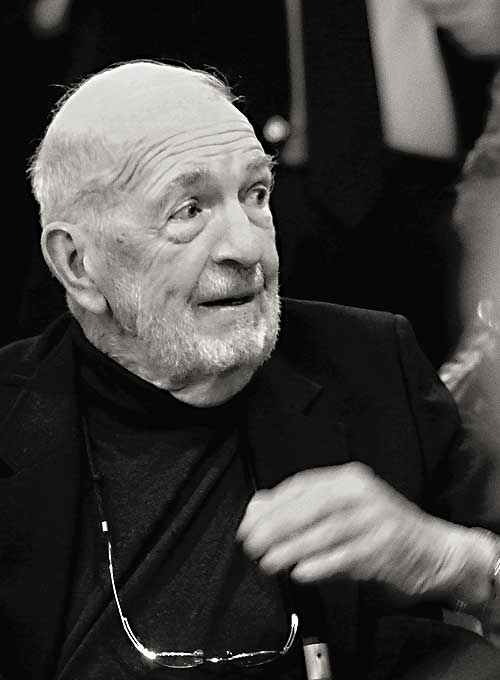

Bob Sickinger propelled the amateur Hull House theatre of the 1960s into national prominence, laying the groundwork for Chicago’s theatre boom.

I met Bob in 1981. My dissertation was on Jane Addams’s Hull House theatre, so he agreed to an interview. A charismatic storyteller, Bob seemed to know everyone. He first struck me as a huckster, but I underestimated him. He said I resembled Harold Pinter. Flattered, I couldn’t help but like the man. I later realized this was Bob’s way of welcoming me into his theatrical world.

In 1962, Hull House appointed Paul Jans as its executive director. Jans shared Addams’s faith in theatre’s ability to help the underprivileged. Bob Sickinger accompanied Jans from Philadelphia to run the theatre and went to work. Bob built an intimate theatre in the new Jane Addams Center, where he staged productions of Albee, Pinter, Brecht and shows like The Connection, Dutchman and The Brig. Critics were knocked out by Bob’s play selection and imaginative direction, and audiences subscribed in droves. Bob also staged readings of edgy new plays in well-to-do homes; these fundraisers inadvertently developed an informed, affluent audience for the innovative, gritty theatre that Chicago would come to know in future years.

Bob quickly branched out. He established a basement theatre in the projects and another in the Parkway Center, both serving black neighbors. He constructed the Uptown Theatre, where he directed musicals ranging from The Boy Friend to Flora, the Red Menace. Hull House began acting classes, a playwrights’ workshop and Intermission magazine. Its summer touring theatre gave hundreds of performances. The Hull House Children’s Theatre flourished with its space-age Captain Marbles series. Bob’s staff included his then wife Selma and future filmmaker Mike Miller. Another filmmaker, William Friedkin, became a supporter.

Scouring Chicago’s community theatres, Bob assembled a corps of actors, including Mike Nussbaum and Bea Fredman. He made Hull House theatre “cool,” so suburban baby boomers flocked to work with him, including a 16-year-old David Mamet, a teenaged Marilu Henner and Jim Jacobs, who later co-authored Grease. Bob involved kids from the street, mixing everyone together. His productions won national attention; celebrities visiting Chicago made sure to attend. David Mamet still views Bob as a key inspiration and example, as well as the best director he ever saw.

Jans resigned in 1969 and Bob soon followed. In New York he directed Off Broadway and in film before leaving the business. But by the 1990s, Bob was again creating new shows in New York. In 2003 I helped organize a Hull House theatre conference at the University of Illinois–Chicago. Bob attended, along with a room full of those who had worked with him, and they swapped stories and shared memories. Though their ringleader, Bob listened more than he talked, laughing appreciatively. This was a family.

In 2011, accompanied by his wife Jo-Ann, Bob attended a conference on Chicago theatre at Columbia College that mixed scholars with Chicago theatre professionals. I titled my paper on him “Who’s Your Daddy?” Bob got wind of this and e-mailed concern. I wrote back explaining it was a slang phrase acknowledging significance and respect. The following week Bob showed up at the opening cocktail party wearing a brightly colored baseball cap upon which was emblazoned, “Who’s Your Daddy?” Those words bore fruit as Bob spent the conference surrounded by young artists, hungry to find out how he accomplished what he did.

I last saw Bob only months after the Chicago conference; he had grown frail. But once he started talking theatre, he sat up, his eyes sparkled and his voice boomed. I asked which Hull House production was his favorite. He paused and then described in detail his mid-1960s take on Camus’s Caligula: He had that small auditorium transformed into a garish, slanting pool, with Caligula and his men preparing a ritual murder dressed in wet suits, gobbling bucketfuls of KFC chicken to Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” He described another of his shows…then another.

Bob said he switched from theatre to making movies because when each show closed, he would sit in his theatre and cry: He and his actors had to abandon their onstage world. Turned out Bob’s spiel wasn’t that of a huckster—he was a remarkable man preaching a gospel of theatrical excellence as community.

Stuart J. Hecht teaches theatre at Boston College. He is editor of New England Theatre Journal and author of Transposing Broadway: Jews, Assimilation and the American Musical (Palgrave, 2011).