The ghost of Margo Jones lives in Dallas. The grandmother of the American regional theatre grew up in the Lone Star State. In 1947, she created the first not-for-profit theatre in the country, Theatre ’47, in Dallas, where she introduced the American arts community to early Tennessee Williams and William Inge (among others). Jones is buried there, and on a sunny four-day weekend in June, she was resurrected.

Theatre Communications Group has held its recent national conferences—at which the nation’s theatre leaders, artists and other performing arts professionals gather for in-depth conversation and problem solving—in Chicago, Los Angeles and Boston, all no-brainers when it comes to theatrical output. This year’s host, Dallas—a center for banking, commerce, telecommunications and health care, with a population of about 1.2 million—could have been seen as a dark horse. It’s not considered a tourist destination, and its theatrical output has been overshadowed by the arts of football and Tex-Mex. But if the 23rd National Conference (June 6–8) was any indication, Dallas is listening to the message Margo Jones imparted: It is a city intent upon creating its own artistic mecca.

The conference theme was “Learn. Do. Teach.”—a phrase inspired by a medical training motto, “see one, do one, teach one” (which in turn inspired experimental director Anne Bogart to use it as a maxim for theatre). The first thing some 750 attendees learned in Dallas was a new lingo: Topical breakout sessions were renamed “learning sessions,” and the agenda was divided into four programmatic arcs (or “majors,” to go along with the academic terminology): Artistic Innovation, Audience Engagement, Diversity and Inclusion, and Financial Adaptation.

Artists who selected the same major (rather than those with similar job titles or budget sizes) met every day in “homerooms” for free-flowing discussions of problems and ideas, which set managing directors and playwrights and publicists rubbing shoulders under the same umbrella. And to really bring the back-to-school theme home, plenary sessions became “assemblies.” “Don’t let us catch you smoking in the bathroom or you’ll be sent to the principal’s office. That’s me,” declared TCG executive director Teresa Eyring at the opening assembly (though one got a sense that there would have been less ruler-slapping in her principal’s office and more gentle reprimanding and problem-solving).

Jones herself was well represented, and not just by her image and the sound of her voice in a high-impact video introduction. Kevin Moriarty, artistic director of Dallas Theater Center and co-chair of the host committee, made the point that Jones and her contemporaries “envisioned the American theatre as a sea of voices, not one but many.” Conference gift bags contained a copy of the 2006 PBS documentary Sweet Tornado: Margo Jones and the American Theater. And speaking from the stage of the Winspear Opera House, nestled in the multiple-venueDallas Arts District, and looking out at the range of theatre folks and independent artists represented, Eyring proclaimed: “Margo Jones’s call for a resident theatre movement has come true!”

Similarly, Laurie McCants, ensemble member of Pennsylvania-based Bloomsburg Theatre Ensemble, urged, “From the ground up, say ‘let it grow!’” at the Friday morning assembly titled “Defining a Movement: Exploring the Movements of the Past, Present and Future.” Having wound their way through the rock-hard soil and stubborn weeds of a recession, the artists at the conference were ready to explore new methods of working outside the traditional institutional theatre models, whether that meant incorporating social media into their plays or learning how to capitalize their financial resources. “Our entire theatre field, all of it, flourishes as a polyculture,” asserted McCants, speaking about the ensemble theatre movement. “We need all kinds of theatre, all over the field, if any of our theatres expect to grow.”

If diversity is an indicator of health, then Dallas theatre is flourishing. That was evident from the range of extracurricular activities (to go along with the in-school theme) available to conferencegoers over the course of the weekend—including a National New Play Network rolling world premiere (Se Llama Cristina at Kitchen Dog Theater), Broadway touring shows (Sister Act), culturally specific theatre (The Dreamers from Cara Mía Theatre Company), a new-play festival (the Festival of Independent Theatres) and site-specific productions (such as T.N.B.by the colorfully named Dead White Zombies, mounted at a former crack house).

According to Moriarty, the Dallas Arts District is the largest in the world, with its shiny, gleaming new buildings, many touched by the hands of world-class architects. Joshua Prince-Ramos and Rem Koolhaas co-designed theWyly Theatre, home of DTC, a futuristic, cube-shaped building with a 600-seat flexible theatre. The district is so new that one venue, Dallas City Performance Hall, did not show up in Google Maps (I learned this the hard way when I got lost en route). All this variety served as the inspirational backdrop to the conference, which spanned six buildings in the Arts District and one off-site. Sessions took place not only in rooms with whiteboards and in glass-walled lobbies, but around the reflective wading pool outside the Winspear, among the Joan Miró and Richard Serra sculptures at the Nasher Sculpture Center, and while petting Rocky the goat during lunch. Rocky had come by as part of a site-specific lunchtime performance. Because…why not? Anything is possible at a gathering of the American nonprofit theatre.

On Thursday afternoon, in a downpour of rain, I poked my head into the Intergenerational Leaders of Color meeting, where 70 attendees were packed almost to overflowing in the Booker T. Washington High School Theatre lobby. The gathering, facilitated by Benny Sato Ambush, senior producing director-in-residence at Emerson Stage in Boston, was a follow-up to a similar meeting at the 2012 Conference, where young and old theatre artists talked about challenges of running a theatre of color and exchanged suggestions. When the conversation turned to passing on the mantle to a new generation, the exuberant Erin Michelle Washington of Soul Productions tapped into the “Learn. Do. Teach.” theme, as she passionately asked the room, “What can we do to help—we, the younger ones?”

The room applauded as Penumbra Theatre founding artistic director Lou Bellamy stood up to offer advice. In 2012, the St. Paul, Minn.–based theatre suspended its programming. Playmaking has since resumed, with help from more than 1,400 donations from corporations and foundations, totaling $359,000. “You have to make sure you are connecting with the community. You have a responsibility to tell their stories truthfully,” Bellamy reasoned, touting the value of community support. In 2005, Penumbra’s individual giving was at 9 percent; now it’s at 40 percent. “Theatres need a tradition of individual giving.”

Another tip for younger artists came courtesy of Marshall Jones, producing artistic director of Crossroads Theatre Company in New Jersey: “I’ll be 50 in August. I have a flip phone. You guys have technology. You can offer us something, you can Facebook this, ‘like’ this, tweet that. You can sell tickets.”

This focus on the importance of building visibility in the community was reiterated in Friday morning’s assembly, titled “Defining the Movement.” Veteran director Adrian Hall, a panelist and the recipient of the TCG Theatre Practitioner Award (see “Awarding the Look Forward”), told a story about the company he founded in 1963, Trinity Repertory Company of Rhode Island.

In 1966, when the U.S. Department of Education initiated the Educational Laboratory Theatre Project, a program to introduce young people to the theatre, Hall felt that coverage in the local Providence newspaper had slighted Trinity Rep’s importance to the community. In an admittedly “ungracious” response, Hall wrote to the paper, saying, “If money came to Rhode Island for theatre and Trinity wasn’t considered, we would take our dollies and dishes and go to where we were appreciated!” The “brouhaha” that followed boiled over the entire state, “which was only 40 miles.” Eventually, with an abundance of local support, Project Discovery was installed at Trinity Rep, and the program went on to introduce theatre to more than a million students over the course of its 46-year history. That meant, Hall said, that “the regional theatre movement was heard around the world.”

Hall, whose appearance generated cheers and a standing ovation, further emphasized the importance of local support by noting, during the Q&A, “Theatre is not just about the people doing it…. Our goal is to find a community, community by community, until we have influenced the whole country…. We are so determined to be better than we are that we forget that…what we’re doing is changing men’s souls.”

That influence comes not through adherence to convention or timidity in programming, asserted Hall and others at various points in the weekend-long conversation, which circled around repeatedly to the importance of risk-taking and bold choices on the part of institutions as well as artists. “Before you can hit a success, you need to be able to fail really large,” playwright Sarah Gubbins told me over drinks at the closing reception. “If you’re not aiming where you can fail large, then you’re just repeating mediocrity. We need to figure out ways to celebrate failure. It’s evidence of risk-taking and innovation.”

The conference was not restricted to attendess only—comments buzzed not just on the sixth floor of the Wyly but on Twitter and on Conference 2.0. On the TCG Circle blog, four online curators culled blog posts based on the four programmatic arcs. And in a partnership with HowlRound TV, discussion sessions were livestreamed, enabling those who were not in Dallas to sample a good chunk of the conference goings-on. The first artistic innovation homeroom on Thursday, led by playwright and arc curator Caridad Svich and Howard Shalwitz, artistic director of D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company, incorporated comments not just from those in the room, but from those watching in cyberspace as well.

In Margo Jones’s time, theatre-in-the-round, the subscription concept and the idea of nonprofit theatre outside New York City were all groundbreaking notions. Perhaps fired up by her example, participants made artistic innovation the most popular arc of the conference. In his address, Shalwitz defined innovation as “working in new and different ways, with the goal of achieving new and different results.” He emphasized the importance of making innovation the norm, by not focusing on what he called “big-I innovations” (such as “the decisions by Zelda Fichandler and Margo Jones to start professional companies outside of New York”). Instead, what’s necessary is “small-i innovations,” which can be done on a daily basis, across multiple departments of a theatre, in a trial-and-error process. “Just a few weeks ago,” Shalwitz said by way of example, “I tried a new approach to my first rehearsal for a new play—by dispensing with the usual table work and asking the actors to just get up on their feet and do the play.”

Svich, who delivered her remarks barefoot because her shoes had gotten wet in the rain, made suggestions of her own, including a shorter planning time for season slots: “Shorter bursts of programming—say, three months at a time—and keep things fast, simple and immediate, to the moment, to the times, to the art and where it is going.” This is the way, she suggested, to create “a more nimble theatre.”

During the question-and-answer portion of the session, a student addressed the difficulty of gaining a foothold in the field as an innovative young artist when “innovation seems to only be reserved for advanced artists.” Svich responded, “Rather than waiting for the space to validate you, sometimes you have to make that space.” Shalwitz added, “There are always artists wanting to break into the field. The larger problem is midcareer artists whose careers have stagnated.”

New ways of rehearsing were brought up again in the Saturday morning learning session “Rehearsing Plays Off the Assembly Line,” where Steve Scott, associate producer of Goodman Theatre in Chicago, recalled a collaboration between his theatre and Spanish director Calixto Bieito on Tennessee Williams’s Camino Real in 2012. Bieito did not establish a concept for the show until the first rehearsal. The production eventually featured actor André De Shields being sexually assaulted while singing a love song. What the Goodman learned, Scott said, was that “we could do pretty much whatever we wanted to do if we approached it sensibly,” including setting expectations and establishing trust within the artistic team.

Frida Espinosa Müller, artistic associate at Cara Mía Theatre Company, talked about the ensemble devising process, which “relies on the actors and their exploration to tell us what the piece is.” Even though the rehearsal process may be atypical, the sense of “not knowing what the piece will be,” even up to the first performance, should not be scary, she contended. Shalwitz, speaking from the audience, agreed: “All innovation strategies require everyone to enter a space of not knowing,” he remarked.

Even though Artistic Innovation was a self-contained major, the theme of learning new processes was prevalent in the other arcs. “My own personal goal for TCG meetings is always to be able to bring something new back with me to my theatre when I get on the plane home,” said Tim Shields during his remarks in the opening financial adaptation homeroom. Shields was co-curator of that arc and managing director of New Jersey’s McCarter Theatre Center. In the homeroom, he talked about how cost-cutting (including staff downsizing and reducing show budgets), increasing earned income (including programming works guaranteed to “put butts in seats”) and a focus on individual giving turned a $1.5-million deficit into a surplus. Shields also admitted that “we still haven’t begun to restore the fiscal and production capability that we once had,” and that the next step is a capital campaign to add to the endowment fund.

Establishing a reserve was also a discussion point in a popular two-part session in financial adaptation titled “Capitalization: Getting Beyond Breakeven.” Susan Nelson, a principal with arts consulting firm Technical Development Corp, discussed creating a capitalization strategy, which was defined as “the accumulation and application of resources to support achievement of an organization’s mission over time.” Capitalization ensures, ideally, that a theatre has enough money to maintain the day-to-day, plus invest in risk-taking, plus have some reserve funds. Still, Nelson also warned that there was no “cookie-cutter” answer to creating such a strategy. Appropriately, TCG’s Fall Forum on Governance (Nov. 8–10) will focus on capitalization. To borrow Shields’s words, the “fiscal adaptation continues.”

The conference encompassed three separate meetings about the Latinos in Theatre movement: a closed lunchtime meeting, a livestreamed learning session and an address by Luis Valdez, hosted by the Latino Cultural Center. “Fifty years from now, perhaps we will mark the year 2012 as a year that spoke the first words of a new creation,” ventured Kinan Valdez, Luis’s son and current producing artistic director of the theatre his father founded, California’s El Teatro Campesino, speaking at the Friday morning assembly. Since 2012, the discussion has expanded onto Conference 2.0 and a Latino/a Theatre Commons, and will no doubt continue at a national convening of Latino theatremakers (the first in over 25 years) to be held Oct. 31–Nov. 2 in Boston. “It is in 2013 that we see the future materialize…. Like the Mayan creator gods, we bring this new world into creation through our conversations,” said the younger Valdez, who was later given TCG’s Peter Zeisler Award (see “TCG Announces Its 2013 Conference Awards Recipients”).

Forging a new world could also be seen as the focus of the diversity and inclusion arc—in the final homeroom titled “Smashing the Glass Ceiling,” the conversation turned to tactics for creating change. Co-presenter Jennifer Bielstein, of Actors Theatre of Louisville in Kentucky and vice-president of the League of Resident Theatres, talked about the efforts of LORT’s newly created diversity task force. Eyring shared TCG’s six-point diversity initiative as part of their strategic plan. One of the initiatives was the Diversity and Inclusion Institute, which kicked off in Fort Worth on the Wednesday before the conference. The homeroom spanned a wide range of topics, from board demographics, to the lack of funding to support diversity initiatives, to how artists of color are held to a higher standard when being considered for leadership positions. Moderator Carmen Morgan asked for a one-minute break to process that last point.

An idea that gained traction in the room from Yale Repertory Theatre artistic director James Bundy and Crossroads Theatre’s Marshall Jones was the Rooney Rule. Implemented by the National Football League in 2003, the rule required that there be minority candidates among applicants interviewed for head coaching jobs. Bundy said that to prove there’s no “pipeline issue” (i.e., the concept that there are not enough candidates of color for the job), “you need to interview people of color.” He added, “Invoking the pipeline problem is patently offensive…. This work has to be done at the grass roots and at the grass tops.”

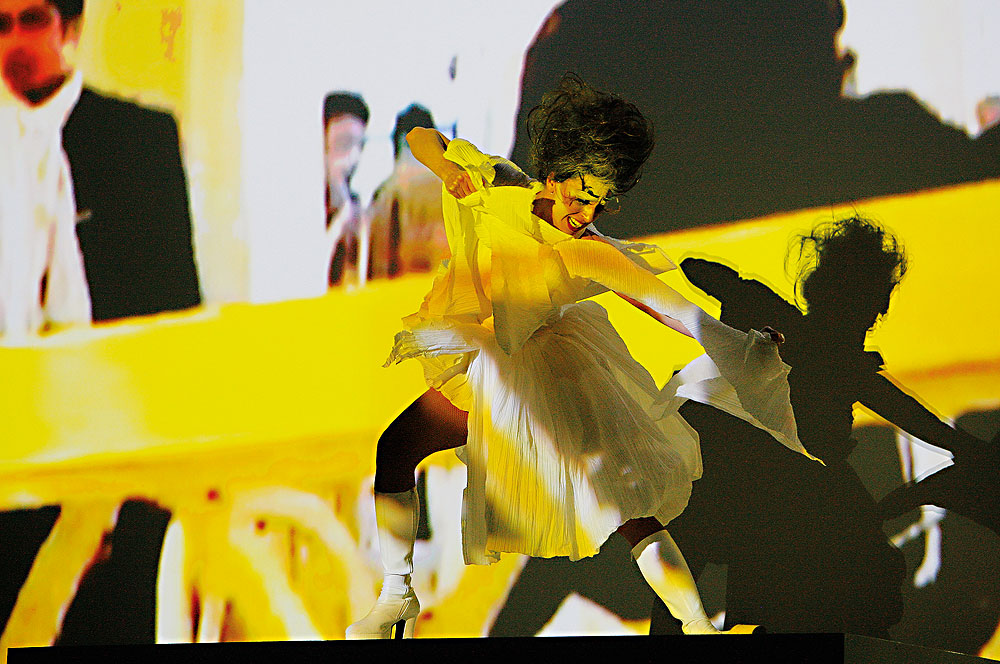

At the opening assembly, titled “Innovation in Action,” the line that received the loudest applause was spoken by performance artist Natasha Tsakos. In response to a question about target audiences for her work, she said, “I find this term really horrible—‘target audience.’ Why would I have a target audience? If the work is meaningful and profound, you should be able to tour it anywhere.” One could say that the conference opened and closed with questions about audiences. Who is our audience? How do we get new playgoers?

Tsakos and hip-hop artist Will Power both performed snippets of their work, and shared the stage afterwords in a conversation moderated by Desdemona Chiang. When asked about what kind of reaction he hoped to bring to the audience with his socially conscious plays, Power smiled and exclaimed, “I don’t know! [They might say] ‘That’s great, let’s go eat.’ I just want to spark questions, conversations…. The most challenging thing is, when you’re innovating, it’s harder to get support because there’s not as much of a social framework for what you do.”

A similar question was asked of Ayad Akhtar in the Saturday afternoon assembly. Akhtar is the author of Disgraced, the 2013 Pulitzer-winning play about a Muslim-American man and his Caucasian wife at a contentious dinner party (published in full in AT, July/Aug. ’13). In his answer, Akhtar referenced German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who said he wanted to create a revolution in the audience, “to present something troubling, thorny, that the audience, on an emotional level, cannot release.” And though Akhtar sometimes writes critically about Muslim culture (so much so that his mother told him to “Stop with this Muslim thing!”), “The best way to tell a good story is not to be worried about the politics of representation.” By writing what he knows about a culture with which he is intimately familiar, “I can perhaps open onto the universal.” He also pointed out that as a playwright, “You’re engaging other people to engage with the work.”

Further talks over the weekend also included ways of getting audiences invested in the theatre without being at the theatre. “The Changing Tides of Digital Engagement,” part of the audience engagement arc, moderated by its online blog curator David Loehr, showcased a range of ways to use social media, beyond organizational Facebook pages or “tweet seats.” Loehr called upon Colin K. Bills, a director and company member of dog & pony in Washington, D.C., who described the company’s interactive show A Killing Game, in which each character had a Twitter handle and patrons could text and tweet during the show. Bills remarked how people who had seen the show but were not in the audience on a particular night still commented on the #KillingGame hashtag: “About 5 percent of the audience will actively contribute to the show’s Twitter feed, and half will follow it.”

When Kelsey Guy, public relations manager at DTC, remarked on the lack of resources and her “struggle to manage institutionally generated content” on Twitter, Loehr answered her with, “Get as many people involved in your organization as possible on Twitter.” He used Goodman artistic director Robert Falls (handle: @RobertFalls201) as an example.

Finally, who’d have thought that the most rousing assembly at a theatre conference would be one titled “Engagement Models from the Museum World”? It was the last assembly but attendees still had enough energy to give the speakers a standing ovation. Maxwell L. Anderson, the Eugene McDermott director of the Dallas Museum of Art, talked about how his museum did away with entry fees in January 2013, which only made up 2.7 percent of a $23-million budget. DMA replaced the charge with a free membership system called DMA Friends, which allows visitors to earn points and rewards when they check in at different areas of the museum. (Think Foursquare, but art-focused.) “Free parking is the number-one reward,” Anderson revealed dryly.

“We are trying to incentivize a combination of social interaction and personal engagement—and convey with that an understanding of the intentions of artists over the past five millennia,” Anderson explained. So far, the museum has signed up 12,781 people, given away 14 million points, and received more than 18,000 visits, including daily drop-ins from a local high school teacher named Bobby. Theatres must charge for tickets out of necessity, an audience member pointed out during the Q&A. Theatres could give away free seats as occasional rewards, Anderson countered. “There are ways of incentivizing through social media, getting new audiences engaged instead of depending on season tickets.”

Nina Simon, executive director of the smaller, $1-million-budget Santa Cruz Museum of Art & History, described how she doubled yearly attendance to 40,000 (in a town of only 60,000) and got the museum in the black (with a surplus) in just one year. The key was focusing on “active participation,” “social bridging” and “fearless experimentation”—which included inviting visitors to contribute materials to exhibits and “bringing in people from all walks of life,” such as graffiti artists and knitters, to encourage diverse interactions and creative collaboration.

In one museum event, she related, called “F My Ex” (the title provoked laughter from the house), which took place in a bar the night before Valentine’s Day, patrons brought in memorabilia from their past relationships, and put it on display. Some older visitors called the event offensive, but Simon wasn’t fazed. “Institutions are afraid of pissing off the people they already have,” she reasoned. “But consider the opportunity you have of reaching people who are on the outside, who don’t even know yet that they’re going to be part of it.” (Simon’s slides can be found here.)

To foster innovation, Simon advised in closing, the artist needs to find a significant problem in need of solutions. “No matter what kind of revolution you want to be in, you’ve got to find an important problem. Selling tickets,” she added, “is not an important problem. Start a revolution in your home world.”