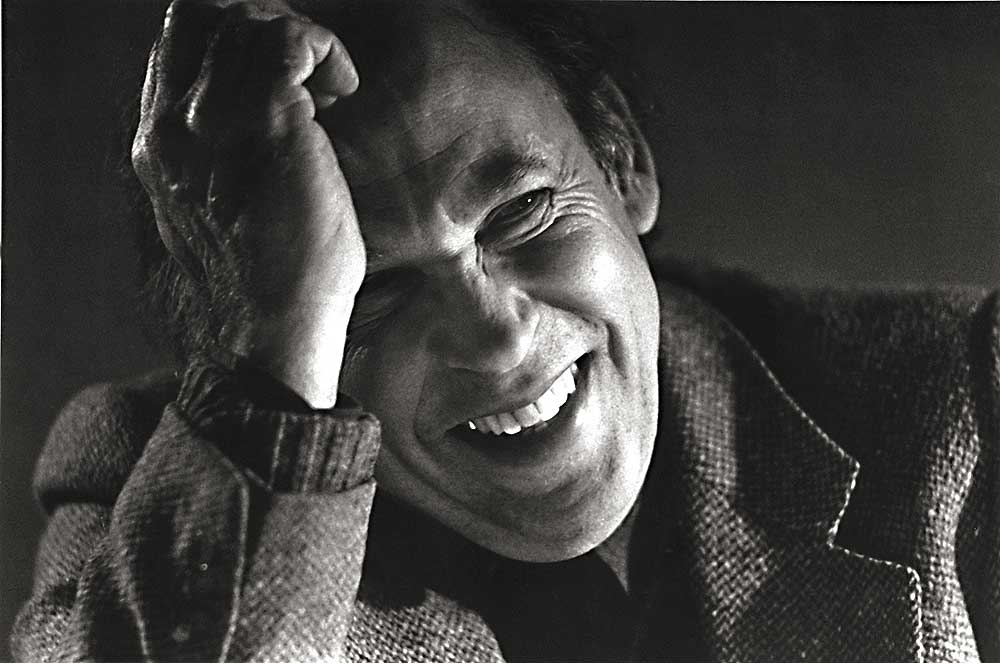

Almost everybody I know from Second City does an imitation of Bernie Sahlins. It usually consists of a wry comment spoken in the cadence of a Maxwell Street merchant (e.g., “You might think differently if you were facing the Inquisition and your name was Ira!”), punctuated by a gesture with a cigar and his trademark dry laugh (heh-heh-heh). I can’t name a noncelebrity who has been imitated by more people.

Bernie’s death has occasioned some misapprehensions in the press, including an AP article that said that he started Second City with “business partners” Howard Alk and Paul Sills. Bernie himself would have corrected that. At the 50th birthday party for Second City in December 2009, he flatly stated, “There would be no Second City without Paul Sills.” Sills’s importance was not as business partner (in fact, Bernie lent Paul the money to be a partner) but as the founding director who created the Second City format—two acts of polished scenes developed improvisationally with a repertory of actors, followed by a set of spontaneous scene-making based on audience suggestion.

What Bernie did was sustain Second City. Today, the Second City brand has considerable value, but it should not be forgotten that the place began its life as an experimental theatre on an investment of roughly $10,000. Bernie figured out a way for it to be that very rare thing—a commercially successful experimental theatre. Not easy given the mercurial temperament of Sills, who was prone to explosions of rage and frustration and abrupt disappearances.

To keep the enterprise afloat, Bernie had to find other people who could take over a show on a moment’s notice, notably directors Sheldon Patinkin and Del Close. And then, having learned from observing his three talented and very different directors, Bernie became quite a creditable director himself. When Sills left to explore the story-theatre form, Bernie found himself the head of what had started as a $10,000 flyer and had become a major cultural institution worth millions. He ran the place through the 25th anniversary, then sold his interest to Canadian Andrew Alexander and went on to explore other interests, notably collaborating with his wife Jane on five editions of the Chicago International Theater Festival, which gave his city its first taste of work from dozens of countries, from Italian commedia projects to Michael Bogdanov’s epic cycle of Shakespeare’s histories to projects from Japan, Lithuania and Venezuela.

Though their friendship extended over decades, Bernie and Del Close had a running argument about the value of improvisation. Del believed in it as a theatrical art form in itself, and he spent his last several years training players to be so proficient that an audience would pay to see a show that they knew would be entirely improvised. Bernie’s view of improvisation was that it was best used as a tool for discovering and refining new material.

To ask who was right misses the point. Del’s perspective is probably best exemplified by the extraordinary team of T.J. (Jagodowski) and Dave (Pasquesi), a pair of Second City alum who indeed created full-length plays spontaneously in front of sold-out houses. Bernie’s perspective is exemplified by projects like TV’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm” and Christopher Guest’s mockumentaries (whose scripts are developed by improvising based on outlines and often feature Second City alums), and, of course, by the continued success of the house he built on Chicago’s North Side. It will celebrate its 54th birthday in December, its first without any of the founding producers.

But I guarantee many will reprise their Bernies. Heh-heh-heh.

Jeffrey Sweet wrote Something Wonderful Right Away, a book about Second City, and is currently writing a book about the O’Neill Center.