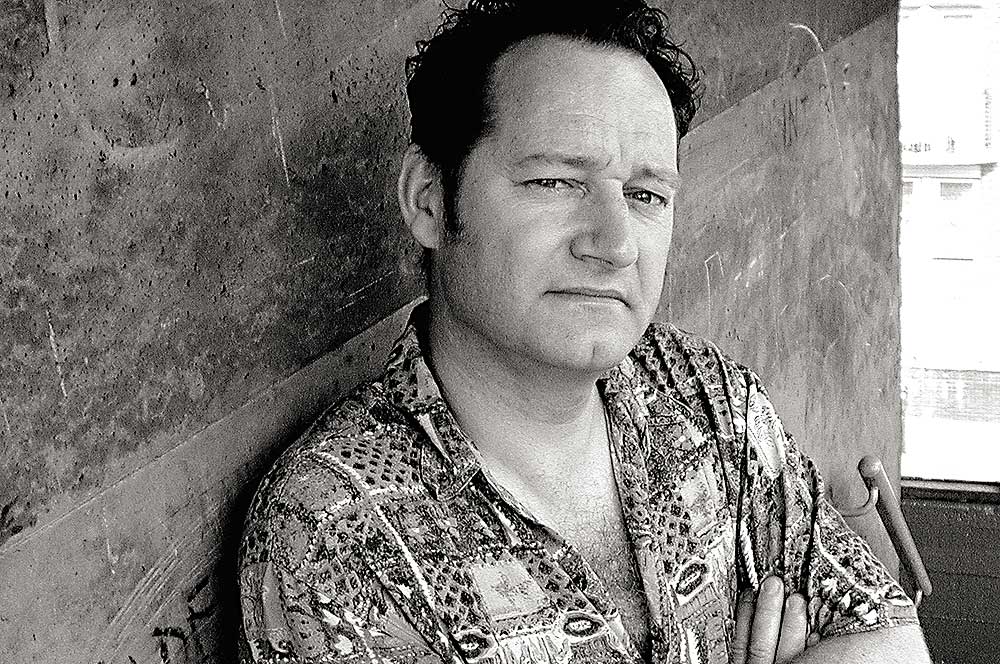

Richard Bean’s One Man, Two Guvnors introduced him to American audiences in its 2012 Broadway run and will see new U.S. stagings this season, including at the Lyric Stage Company of Boston (Sept. 6–Oct. 5). But he’s better known in his native England for politically impious comedies like England People Very Nice, Under the Whaleback and The Heretic (which gets its U.S. debut at Raleigh, N.C.’s Burning Coal Theatre Company Sept. 12–29). Bean spoke to American Theatre while in the midst of writing a new play for the National about the Rupert Murdoch phone-hacking scandal.

You’re known in the U.S. for One Man, Two Guvnors, but that’s not really characteristic of your work, is it?

I don’t think it is, really—it’s the only out-and-out comedy I’ve written. How do people file me? Black comedy, controversialist, counterintuitive, always trying to rub people up the wrong way.

Right. A lot of your work has been topical, like that of David Hare, except from a different point of view.

You mean politically? Well, some people have accused me of being slightly to the right of David Hare, but I’m not sure that’s true. What I like to do is debunk orthodoxies. I don’t want to get into whether David does that or not, but I don’t see the value in serving up to the audience what they already think, whether it be about global warming or the IRA or multiculturalism. I write from experience, and I don’t live in Hampstead, like David Hare does. I’ve been spat at in the street. I don’t think he’s had that happen.

You’ve worked some odd jobs on your way to the theatre.

It’s a funny old career. I worked in a mass-production bread plant and bakery. I can absolutely say, from a writer’s point of view, that it’s the best thing I could’ve done, because I was locked up for 12 hours a day with some of the craziest guys I’d ever hope to meet. I was the only bloke without tattoos or a prison record. One guy came in on a Wednesday and didn’t come in on Thursday; we wondered where he was, then he was in the papers on Friday—he had tried to rob a bank.

Most of these guys were fisherman, but our fishing industry in the town of Hull collapsed, so they all came back to work in the factories. If I concentrated on listening to their stories, I could get seasick. That kind of deep-sea fishing is the last wild food—it’s basically hunting. And they had done it during the Cold War, so there were Russian submarines about. It was like The Odyssey every night. It was fabulous. I was 18, and I didn’t think about it for years. But when I was 42, I wrote down a night-shift of that job, and that became the first play I had produced, Toast.

And between those two points…

I worked as an occupational psychologist, administering psychometric tests, but I kind of burnt out on that when I was about 35. So I started writing and doing standup comedy as part of a new wave in the 1980s—I did that for six years. I was okay, but I wasn’t brilliant.

As colorful as that bread factory job was, wasn’t there also some theatrical fodder in occupational psychology?

People often say that to me, and I usually say no. I may be well wrong. I’m just more comfortable writing what you would call blue-collar comedies. The Heretic was the first play I did where most of the characters are educated and middle-class. It was hard—not because I’m stupid, I’ve been to university, and I know how university lecturers talk. But I’d never relished it, I guess; I never thought it was entertainment.

So are you, like the lead character of The Heretic, a climate-change skeptic?

I count myself as a climate-change skeptic, but I don’t question the laws of physics. I’m not a denier. But the problem is we’re trying to make rules about a stochastic or chaotic system, like human behavior or climate, in which anything can happen, and to expect some kind of conformity. It always confounds us, nature. All scientists should be skeptics; it’s almost the definition of science.

What was your first theatrical experience?

At my local theatre, which was called the Hull Arts Center, I saw an act, like a cabaret, not a play—it was a character called the Masked Poet, and he dressed like Superman. I think it was Roger McGough, actually, one of our Beat poets. He swore a lot, which I thought was quite interesting. And I saw The Changeling and I was fascinated; somebody got a finger chopped off in that, and I completely believed it.

What would you say is the main difference between British and American theatre?

Ticket prices. That influences your response. In the case of One Man, Two Guvnors, we were all very worried that American audiences wouldn’t get the humor, but they laughed harder than English audiences. They’re more open to being entertained, more giving. You’re a more positive race, aren’t you?

Will the British monarchy ever go away?

I don’t think so. They might breed themselves out of existence. There’s a joke in my house that I don’t know the names of the royal family. I honestly can’t tell you who’s just had a baby.