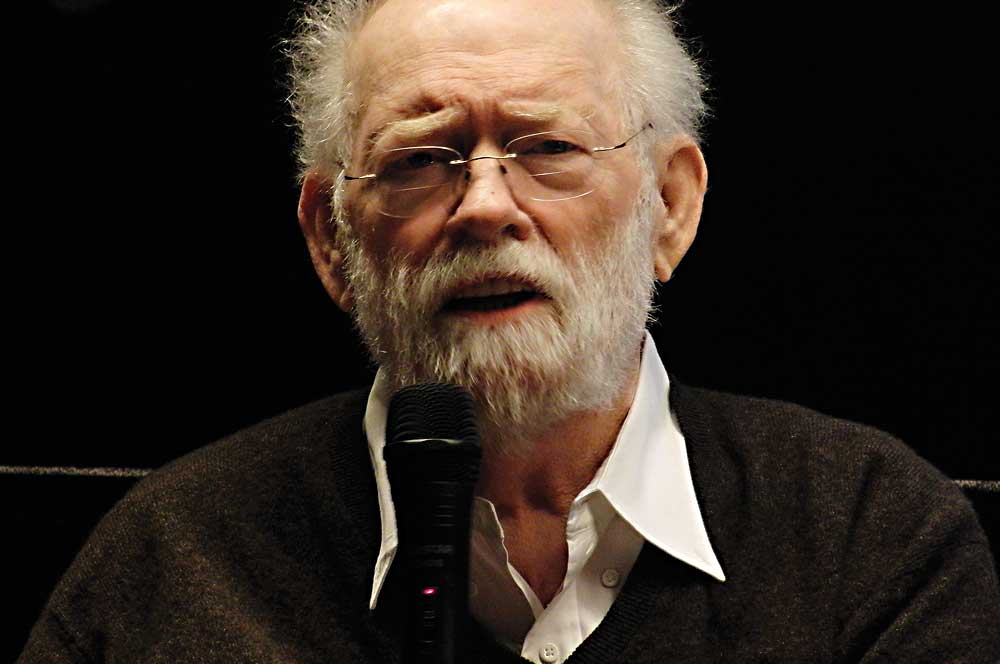

There is too much to say about Philip Arnoult. A bounding impresario and advocate of new theatre for more than 40 years—first as founder and ringmaster of the storied Baltimore Theatre Project (where he served from 1971 to 1990), then as the gregarious lone wolf behind the Center for International Theatre Development (1990 to the present)—he has done more to keep the American stage in conversation with the rest of the world than almost anyone else.

Now in his early seventies, the Memphis-born, Baltimore-based Arnoult continues to cultivate a rich theatrical career as vital as it is idiosyncratic. Its signposts are an abiding interest and belief in international dialogue; individual artists and companies; and the health of American theatrical art “beyond the capitals,” as one of his more recent projects is titled. (Full disclosure: I have been a part of that larger Russia-U.S. project of CITD, as well as the recipient of several Arnoult invitations to festivals and work abroad.)

By now a long list of productions and festivals, as well as training programs and community initiatives, bear his name or stamp. But Arnoult’s many far-sighted contributions to the theatre reverberate perhaps most powerfully in an enduring web of personal relationships too intricate to map, as the testimonials of friends and colleagues suggest. Many of these relationships have been the foundation and outcome of fruitful long-term projects of the last 25 years, geared to international artistic collaborations with the Netherlands, Eastern Europe, East Africa and Russia.

Having cut his teeth as an actor, director, producer, teacher and advocate (during his long association with UNESCO’s International Theatre Institute from 1975 to 2002), Arnoult seems happy these days to play the matchmaker in many an artistic enterprise, working at one remove from producing in the crucial if generally underappreciated capacity of cultural liaison and canny networker. In this role he wields both a rare set of talents (including an ability to find the right allies, and a DIY knack for piecing together disparate resources) as well as strong relationships with key foundations and institutions, including the New York–based Trust for Mutual Understanding and Baltimore’s Towson University.

But though his role is often subtle, his impact is deep. I write this having just returned from Budapest as a guest of CITD, where I attended the Hungarian Showcase 2013, an impressive selection of leading work from independent and state-sponsored theatres. In a very basic sense, the showcase could not have been conceived without Arnoult: He wrangled a large international delegation of presenters and journalists for the March festival, which comes at a time when Hungarian theatre has been both threatened and animated by a political shift to the right that has imperiled the country’s civil society at large.

“Philip’s activity in this showcase is really crucial,” Andrea Tompa, head of the Hungarian Theatre Critics Association, explained in February via Skype. “We were not expecting that so many people, festival directors and writers, would be so interested in a Hungarian showcase. But Philip suggested that since we’re doing an event for the Americans, why shouldn’t we open this event for the rest of the world? So you see, Philip is moving a lot of things. Sometimes he probably wants to be invisible, which is fine. But without Philip—as a person, producer and somebody who inspires you—this thing wouldn’t happen.”

Arnoult’s theatre calling began in the late ’50s, in the doldrums of high school in hometown Memphis, Tenn. There, in an aimless period—“I was going to hell in a pushcart,” he remembers—he stumbled on a play rehearsal. After landing a small role in the production, he knew what he’d be doing from then on. The day after graduation he started paid work as an actor at Memphis’s old Front Street Theater. He started directing too, while pursuing studies at Memphis State and a graduate degree at Washington, D.C.’s Catholic University. He’s not slowed since, although his focus has steadily shifted and enlarged.

“I used to tell people,” Arnoult explains by phone from his home in Baltimore, “that I started out as an actor, then I became an actor-director, then a director-actor, then a director-producer, then a producer-director. Then I became a producer at the Theatre Project. And then I became whatever I am now.” And what is that, exactly?

“The closest I’ve been able to come to answer that is the French term, animateur,” offers Arnoult. “Also, more prosaic—but probably closer to the actual work that I do—is ‘connector.’ I have a pretty good nose,” he says. “And I think I’ve shared with you my three moves?”

That phrase refers to his modus operandi, refined over a lifetime of theatrical experience and ardent networking into a limpid unfussiness.

“First, I go in and get to know artists—not necessarily their work (that happens at a lot of different points). Then I make this synapse of connecting: ‘Robert, do you know so-and-so? I think you should, and here’s why. Let me help the two of you get together.’ That’s my second move. And my third move is backing off—letting them get on with it. No sticky fingers.” That may be true, but the prints are everywhere.

“If you look at it as connect-the-dots,” suggests Stacy Klein of Massachusetts’s Double Edge Theatre, “inevitably Philip’s dot is a central point for all the other dots that are connected—not just in my theatre but in many places.”

Arnoult’s allegiance to the wider theatre world dates back to his days at the Theatre Project, initially underwritten as a free theatre by Antioch College and run with his collaborator and life partner Carol Baish (who was BTP’s managing director). Inspiring Arnoult and Baish were new companies coming from unexpected places like Atlanta and Knoxville—a nationwide movement of regionally born and oriented art theatre that Arnoult savored.

Also seminal were his encounters with a European avant-garde that included Jerzy Grotowski (who called on Arnoult in 1974, inviting him to come to Poland with a group of Americans the following year). With colleagues at Pittsburgh’s 99c Floating Theatre Festival and Philadelphia’s Wilma Project (now the Wilma Theater), Arnoult helped build a pipeline of new work—and a community—emanating from the alternative theatres of the 1960s and ’70s. BTP opened the doors to itinerant companies like Milwaukee’s Theatre X and put Baltimore on the map as a serious home for experimental work in both theatre and dance.

And then there was the inimitable Ellen Stewart, an early inspiration and a longtime Arnoult ally. “Over the years I was with Ellen in a lot of different places,” he recalls. “With ITI we were together in Bulgaria, East Germany. She was a real stalwart of opening up what was essentially a European sensibility to a much more global sensibility. I probably saw her more as the model than anybody else in America.”

“Philip is really one of the great internationalists,” enthuses Molly Smith, artistic director of D.C.’s Arena Stage, who as a student knew Arnoult from the New Theatre festivals he co-produced in Baltimore in 1976 and 1977, which she calls “revelatory,” but met him professionally when he invited her to Hungary in 2000.

One small illustration of Arnoult’s humble magic: Smith brought the brilliant young Hungarian director János Szász to Arena after that first trip, which took place under the auspices of the Eastern and Central European Theatre Initiative—a five-year project of Arnoult’s CITD supported by the Trust for Mutual Understanding, which sought to connect young directors in post-Soviet Hungary, Poland, Romania and Russia with major American theatres. Szász, who directed a radical interpretation of A Streetcar Named Desire at Arena, also connected with Robert Orchard, another Arnoult guest on that 2000 trip, and ended up working extensively at ART. Szász continues to work on projects in the U.S., including this summer’s adaptation of The Master and Margarita at Bard College.

Look closer still and you’re bound to find more Arnoult prints—on a 2012 monthlong program of Dutch youth theatre at New York’s New Victory Theater; or maybe across a flurry of translations and American productions of new post-Soviet Russian drama, or on translations and productions of American plays in Russia; and many, many more places besides. As this article has noted, there’s too much to say.

And yet, because he’s come to prefer the vital but less visible role of artistic matchmaker, the modest number of words in print or online belies Arnoult’s transnational reputation. Don’t speak the language in Wroclaw? Ekaterinberg? Pécs? Kampala? Try saying, “Arnoult.” It might prove a better indication of the countless productions, programs, relationships and careers that owe their existence, in one way or another, to the deceptively simple M.O. of this globetrotting agent of theatrical exchange.

Critic and journalist Robert Avila is a frequent contributor to this magazine.