“We need you.” The date was December 2009, the place was the first TippingPoint USA Conference—a convening of artists and scientists focused on climate change, co-hosted in New York City by Columbia University’s Earth Institute, the CUNY Institute for Sustainable Cities and the British Council USA. Describing climate change as “the most complicated human challenge we’ve ever deliberated on,” sustainability economist and Earth Institute director Jeffrey D. Sachs delivered a plea urging artists of all disciplines to join scientists in their efforts to personalize climate science and disseminate it to a wider audience.

There were fewer than 50 artists in the room that day, but it seems that the field at large heard the call. An increasing number of theatre projects over the past few years have not only addressed issues related to climate change but have involved scientists in the process. For the most part, artists are confident they can make an impact. But how do scientists view such efforts? Are artists rising to Sachs’s challenge?

Elke Weber, professor of psychology at Columbia and co-director of the Center for Research on Environmental Decisions (CRED), was interviewed by New York City–based ensemble the Civilians for its musical The Great Immensity, which premiered at Kansas City Repertory Theatre in February 2012. A cautionary tale about what drastic measures might be needed to make the world understand the severity of the climate crisis, The Great Immensity follows Phyllis as she tries to uncover an activist plot related to the next international climate summit. The play marks the start of the troupe’s “Next Forever Initiative,” an ongoing commitment to produce work with an environmental conscience. With funding from the National Science Foundation, the project has expanded to include a website, www.thegreatimmensity.org, featuring blog posts by the play’s characters and videos about artists creating environmental work.

Weber’s research concentrates on decision-making in situations of uncertainty and time delay. It shows that we focus first on the immediate consequences of our decisions and tend to ignore the costs and benefits of actions that are farther into the future. Applied to climate change, this means that because the consequences of current inactions won’t be felt for generations, we are naturally hard-wired to ignore them and focus on more timely concerns—like the discomfort of reducing our energy consumption. As The Great Immensity’s Phyllis puts it: “We’re the generation who can actually do something. The problem is we don’t, because we perceive it as a problem in the future.”

However, the situation changes when people are prompted to act based on longer time horizons. So for Weber, one of the crucial ways that theatre can effectively battle climate change is to focus our hearts and minds on the future: “Engaging people through the arts—not necessarily in ways that are alarmist and fear-provoking, but in ways that are thought-provoking—can remind them of their long-term goals. The arts can comment on abstract things—like the sustainability of planet Earth—so much better than statistics can.”

Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicist Robert Jaffe shares Weber’s view: “Climate change has a different nature than a lot of scientific, medical or biological problems the world has faced in the past, because the timing is so unusual and so badly suited to human cadences. The carbon dioxide we’re loading into the atmosphere now is going to affect the next thousand years but the effects won’t be felt for a few generations. Human beings don’t know how to process that.”

As a member of the advisory board of Catalyst Collaborative@MIT—a collaboration between a group of MIT scientists and artists from Cambridge, Mass.’s Central Square Theater—Jaffe was instrumental in getting CST to look for a climate change play to include in its 2013–14 season. (Full disclosure: CST announced it will produce my own play, Sila.) As Jaffe explains: “Human-generated climate change is the fundamental scientific issue of the 21st century. People will be judged in retrospect by the extent to which they either took up that challenge or ignored it. So when we talked about possible topics for theatre at a meeting of the Catalyst Collaborative board, I said, ‘How can you ignore this?’”

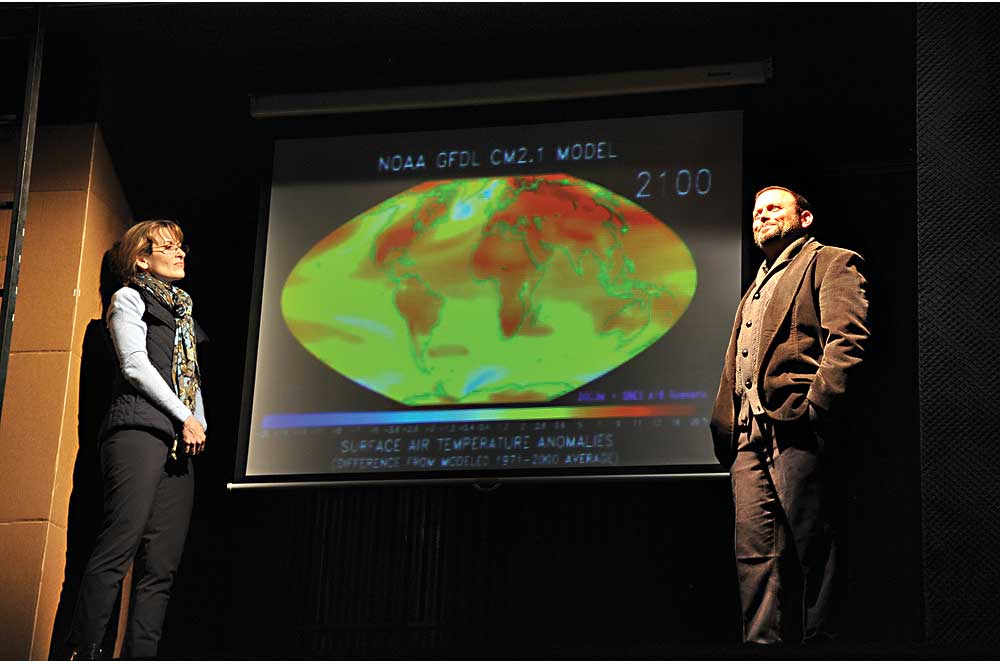

Caring about a future that will not affect us personally requires a level of engagement that goes beyond a simple understanding of the facts. Cynthia Hopkins’s This Clement World—a personal, multimedia, music-infused journey to the Arctic and beyond inspired by a Cape Farewell sailing expedition—premiered at Brooklyn’s St. Ann’s Warehouse in February 2013. In a talkback after one performance, Gavin Schmidt, a climate modeler at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the author of the popular science blog RealClimate, stressed the need to tell stories. “Stories are why we do things,” he said. “The narrative we have in our head, the reason why we get up in the morning—it’s a story.” The only way we are going to be galvanized into action around climate change, Schmidt believes, is through personal connections to stories and metaphors.

The truth of that notion is underscored by a scientific explanation for the relationship between emotion and action. CRED’s publication The Psychology of Climate Change Communication explains that the human brain has two different processing systems—experiential and analytical. The experiential processing system controls survivor behavior and is the source of emotions and instincts (feeding, fighting, fleeing, etc.). The analytical processing system controls analysis of scientific info. There is strong evidence that the experiential processing system—the main way we engage in the act of watching a play or experiencing a work of art—is the stronger motivator for action. Thus, the engagement of both emotions and intellect is more likely to lead to a change in behavior than the engagement of intellect alone.

This Clement World personalized climate change through the metaphor of addiction. As a (now recovered) drug addict, playwright Hopkins was concerned only with the here and now; she had no thought about the future. Her inability to envision the future allowed short-term satisfaction to trump long-term consequences, just as our society’s addiction to fossil fuels trumps our efforts at taking drastic measures to curb greenhouse gas emissions. By drawing a parallel between the two situations, the metaphor allows for an understanding of the global crisis on a far more personal level. And, perhaps paradoxically, it instills a sense of hope. Hopkins was able to transform her behavior in ways that she didn’t think were possible—her own personal recovery suggests that recovery for our entire species might be within our reach.

Like Weber, Elena Shevliakova, a Princeton University climate modeler, was interviewed for The Great Immensity. Shevliakova describes theatre as a mirror that reaffirms ideas present in the culture and encourages people to engage more deeply with those ideas. She cites, as an example, the use of green technology (wind and solar power, electric cars, etc.). Theatre can reinforce positive behavior by showing audiences they are not alone in embracing those technologies; their individual choices add up. Weber concurs: “Plays can debug the myth of how ineffective the actions of an individual are. They might be a drop in the bucket, but if you multiply by 200 million, it makes a huge difference.” In that sense, like the climate itself, theatre can be a positive feedback loop.

The communal aspect of the live theatre experience also has the potential to influence people’s behavior. According to Weber, decisions that require a personal sacrifice in order to mitigate an environmental impact are more likely to be positive if the person making the decision is in a group setting. When asked, for example, to switch our electricity supplier to a clean-energy supplier—clean energy being more expensive than its traditional counterpart—we are more likely to make the switch if we are presented with the choice in a community meeting rather than in the privacy of our home. Being surrounded by people, and reminded that we are not alone in the world, makes us more willing to consider how our actions affect others.

Community also means bridging the gap between scientists and the general public. Nicole K. Davi, a postdoctoral research fellow in paleoclimatology at Columbia, collaborated with Superhero Clubhouse, a group of artists and advocates working in environmentalism and theatre, on Field Trip: A Climate Cabaret, presented at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory’s annual Open House in October 2012. Based on the lives and work of seven climate scientists, Field Trip weaves together a series of whimsical scenes that highlight the creative aspect of science and translate scientific research into poetic musings and songs.

For Davi, who expressed great enthusiasm about the project, the need to humanize scientists is real: “I don’t think people have a very good understanding of who scientists are or what they do. And I don’t think people realize how often scientists don’t find what they want or just completely fail.” Theatre can encourage people to learn more about climate change by making scientists and the process of science more accessible. “People are interested in connecting to scientists and liking them,” Davi adds. “They want a human-focused story that can help them understand the challenges scientists face, what scientists do and why it’s important.”

If theatre can, in fact, have an impact on the global conversation about climate change, why aren’t we seeing more plays about this issue? For one thing, as Shevliakova points out, incorporating science into works of art is challenging. In addition, political theatre—if we see climate change as a political issue—doesn’t sit comfortably within the American theatre ecosystem. “It’s a noble endeavor to try to use the tools of an artist to be on the right side of an issue like this,” Jaffe remarks. “I’m reminded of how dangerous it is, though, because the reputation of politics and theatre—and politics and art in general—was so damaged by the ideology of the early 20th century. The Soviet Union and the fascists really understood the power of propaganda. They gave a very bad name to the integration of political ideas into theatre.” Finally, creating work that relies heavily on philanthropy for its sustenance, in an economic system dominated by forces that have little to gain from increased public awareness of climate change, adds to the complexity of the endeavor.

Yet despite the difficulties, scientists believe in the potential of artist/scientist collaborations to bring climate change to the forefront of public consciousness. “Playwrights are here to help us experience the full range of human emotions and the complexity of human relationships,” Weber notes. “Having the two groups work together and develop joined messages makes for a rich experience. Scientists give a good base to the playwrights, and the playwrights are able to put the facts into a more emotional context.” Some scientists, like Davi, are even looking for more ways to include artists in their research. But regardless of the outcome, there is one undeniable benefit that emerges from these collaborative relationships: They model, on a small scale, the very behavior that is needed to address the same issues on a much larger scale. As one of the scientists in Field Trip sings:

We’re on a field trip

We’re in the field

To see what

Collaboration can yield.

Let’s hope theatre artists respond in ever greater numbers to Professor Sachs’s earnest challenge.

Chantal Bilodeau is a New York–based playwright and the author of the blog Artists and Climate Change.