“The United States government spends more on a single day on the war in Afghanistan than its annual budget for the National Endowment for the Arts,” Cynthia Cohen will tell you, reciting the statistic with a certain degree of exasperation. “The issue is society’s lack of investment in creativity, versus its habit of addressing conflicts destructively. We in the arts can transform conflicts creatively for the betterment of everyone.”

As director of the Peacebuilding and the Arts program at Massachusetts’s Brandeis University, Cohen has worked for the past 15 years with poets, painters and actors to encourage global peace through education and performance. The program’s arts-driven initiatives have encouraged co-existence in communities in conflict ranging from Northern Ireland to Sri Lanka, among other world hotspots.

A soft-spoken New England native whose political views were shaped by the civil rights and antiwar movements of her college years, Cohen became a storyteller and self-described scholar-practitioner, as opposed to an activist. Those skills have been particularly useful in Peacebuilding and the Arts’s most recent undertakings, a two-volume anthology called Acting Together: Performance and the Creative Transformation of Conflict (which Cohen co-edited with Roberto Gutiérrez Varea and Polly Walker) and a companion documentary film, Acting Together on the World Stage (directed by filmmaker Allison Lund).

The anthology and the film (created in collaboration with Theatre Without Borders, a network of theatres, organizations and international artists with complementary concerns) are intended for theatre groups and peace-building practitioners, educators, students and citizens working in an array of fields.

Set in troubled regions throughout the world, the film focuses on theatrical and ritual performances and their social impact, and comes with an educational toolkit. Cohen and her team have translated the documentary into six languages, with subtitles in Arabic, Hebrew, Japanese, Sinhalese, Spanish and Tamil. But money is still needed to cover production costs and disseminate the multilingual disc.

To fill the gap, she and her colleagues have launched an unusual global campaign, identifying 51 organizations—among them underfunded theatre groups on the front lines in conflict zones—to receive the package. The team will then seek an equal number of individuals and institutions to underwrite the resources at $300 a pop. Cohen hopes the campaign will be completed this summer, though she knows challenges abound, given the economic climate. But she sees a subtle shift in attitudes toward engaging artists in the problems confronting dysfunctional regions.

“People in business, health care and even law are realizing the linear, rational approach to solving global problems is not sufficient,” Cohen contends. “There are places where artists are being brought to the table sooner. And after a highly placed official from the U.N. Development Program saw our documentary, he said that in the future he would be bringing artists into the process whenever peace-building initiatives are shaped.”

Theatres in trouble spots, even in the U.S., often function in the midst of violence and its aftermath, Cohen observes. She points to Daniel Banks’s Hip Hop Theatre Initiative, which “strengthens the voice of young people of color and addresses issues of classism, racism, ageism and homophobia,” and to the work of John O’Neal, a leading theatre artist of the Civil Rights Movement, who “continues to work in high schools, prisons and community settings in New Orleans.”

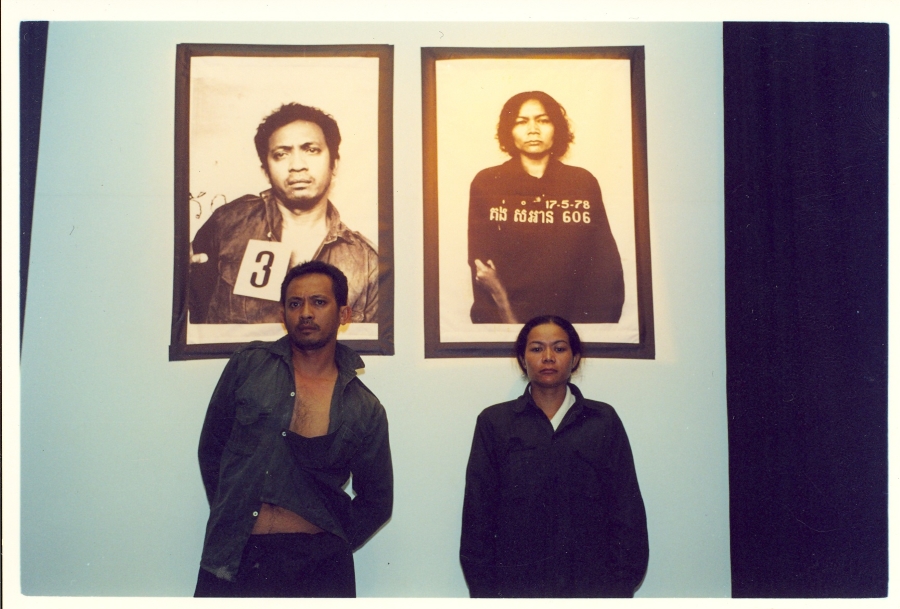

On the international front, she cites Serbia’s DAH Teatar and Peru’s four-decade-old Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani as prime examples of theatrical peace-building. During a long and brutal civil war in Peru, the wretched atrocities suffered by thousands of indigenous people would never have been documented had it not been for the latter theatre, whose actors led rituals of acknowledgment and mourning and prepared witnesses to tell their own stories before the new government’s truth commission.

“Yuyachkani’s powerful performances returned a sense of dignity to indigenous communities, and their impeccably crafted productions brought their stories to the elite communities of Lima as well,” Cohen reports.

Nonetheless, she insists the goal of peace-building performance is not necessarily to advocate for any single political viewpoint, but rather to “create spaces for conversations that raise questions and honor a range of views, which is very precious in a context of violence.” Indeed, people with extreme politics at opposite ends of the spectrum are often in the audiences and on stage together.

Working with communities in conflict often begins with the challenge of language, but Cohen says she has found that far more significant than overcoming language barriers is the ability to build relationships of trust—which requires “listening, being humble and acknowledging the dynamics of power.” As an American, she stresses, it is important to understand the role the U.S. has played historically in a given region and how our country is perceived there.

Some efforts can backfire. “In an attempt to dignify suffering, we can end up re-traumatizing people,” Cohen cautions. “Sometimes with the best of intentions, the unequal dynamics in the society are simply replicated, rather than transformed, in the theatre production. In addition, sometimes a sacred ritual borrowed from one cultural setting and used in a different context can violate the sensibilities of both participants and witnesses alike.”

Colleagues in the field affirm that Cohen is addressing very real needs. “Cynthia’s work in the field of coexistence awoke my imagination, and I began to consider how to apply coexistence and conflict-resolution analysis to intercultural theatre exchange,” avows Theatre Without Borders co-founder and director Roberta Levitow. TWB steering committee member David Diamond has high expectations for what he calls Cohen’s “training for trainers,” praising the new anthology-film-toolkit package as indispensible for “professionals who will spread its stories, methodologies and insights to students and practitioners.”

It was at Wesleyan University, where she majored in ethnomusicology, that Cohen developed her talents as a storyteller, which continued in her years as a graduate student in urban studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In Cambridge, she became the founding director of the Oral History Center, an organization that addressed racial tensions and celebrated diversity through the sharing of stories, and went on to earn her doctorate in education from the University of New Hampshire.

“From my own experiences as a storyteller, and from the dozens of artists I worked with at the Oral History Center, I know the experience artists have in channeling something outside of themselves,” she notes. “I know when you can reach an audience, and open people up to new ideas, and enable them to imagine what may not yet be real. You can feel the shift of energy in the room.”

But, in the end, Cohen also realized that the transformative powers of performance—or, indeed, any of the arts—was not enough without the benefit of strategies to address the myriad of contingencies communities face in strife-filled areas. She looks forward to the time when the Acting Together documentary will also boast subtitles in French (especially for presentations in West Africa), Swahili, Cambodian and Serbian, as well as the languages of Afghanistan and Nepal. She is also envisioning “the building of an infrastructure—physical or virtual—where practitioners can come together and learn from one another. I’d like to see a network of people who know what’s happening globally, connected to regional hubs where they can link theatre artists with each other and with the expertise emerging in the peace-building performance field from regions around the world.”

Equally important, Cohen hopes that people from all walks of life value the efforts of artists-cum-peacemakers. “A profound shift is taking place in how people understand the role of culture and the arts,” she asserts. “Activists and organizations working to improve our world are poised to take their rightful place.”

Simi Horwitz writes frequently about the arts. For more information about the Acting Together resources and the global campaign to disseminate the documentary in multiple languages, visit www.actingtogether.org.