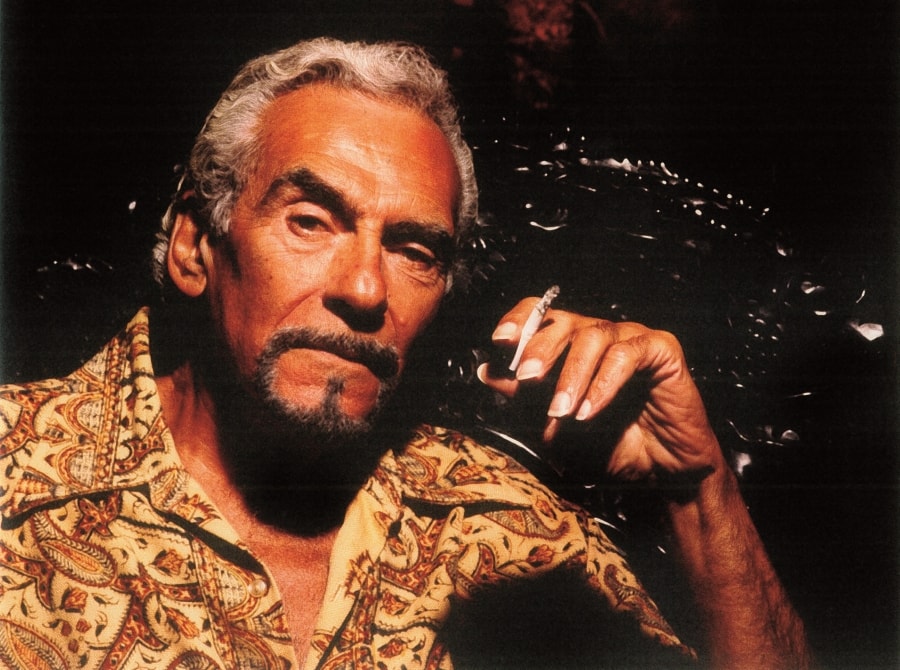

Leon Katz is a living legend—a term I use not only to irritate him, but because four or five generations of actors, playwrights, screenwriters, dramaturgs, designers and directors still speak of his classes on play analysis in hushed, reverent tones. We acolytes who chose the path of teaching still comb the yellowed pages of our 25-year-old lecture notes, hoping to catch some of his fire in our own lectures. For taking teaching to an evangelical height, Katz was awarded the 2004 Association of Theatre in Higher Education Career Achievement award, joining the ranks of Edward Albee, Augusto Boal and Anne Bogart. He has earned epithets such as “the Michelangelo of all lecturers” from scholar Meiling Cheng, and “Gandalf” from actor Chris Noth.

My favorite description of Katz’s lectures is from my colleague Mark Lord, chair of drama at Bryn Mawr: “It was like having your head explode. Again and again and again.”

So the publication of Katz’s book on play analysis, as he nears age 94, is both long-awaited and surprising; I think we’d given up hope. The aptly, if unpleasantly, titled Cleaning Augean Stables turns out to be not merely an exercise in nostalgia for the initiated; it’s indispensable for anyone seriously interested in the art of the play.

In the book, Katz catalogues an encyclopedic knowledge of what Cheng describes as “conceptual paradigms across genres and periods.” The objective is to demonstrate the fallacy of what Katz calls “pieties,” unquestioned “rules” of dramatic construction. Testing them against the dramatic corpus, and situating them within the history of thought, he traces the development of theory, or “value systems,” in response to shifts in economic and political realities. In the chapter “Packaging Meaning,” for instance, Ibsen’s Rosmersholm is analyzed through the lenses of “brilliant, influential” studies by Freud, Shaw and Brian Johnston, showing that different, even mutually exclusive, analyses may be persuasive, but all supply what critics look to find.

Katz describes Aristotle’s fourth-century B.C. consideration of fifth-century B.C. plays, Poetics, with its checklist to evaluate plays for quality and insufficiency. Katz notes that by Aristotle’s value system, among extant Greek tragedies only Oedipus would make the cut as a very good play. Even today, after Beckett and Fornes, Antonioni and Young Jean Lee, theatre departments, film schools and an industry of how-to gurus erect pedagogy around what Sarah Ruhl has called “the enshrinement of the male orgasm,” but is better known as Freytag’s Pyramid.

Dumbed-down education reduces play analysis to that which can be answered on a multiple choice test. Regurgitated, distilled and diluted, Aristotle’s Poetics has long been overprescribed, like Ambien, and to similar effect. The homogenization of drama, film and television leaves us with the reassuring but soporific feeling that we are having the same experience over and over again. We are.

Katz even challenges the holiest certitude: “Conflict, like the Immaculate Conception, came late to the list of eternal verities. It occurred to no one until the very early 19th century that conflict was the essence of drama…. One might shake one’s head in wonder at how it was possible that so fundamental a principle of dramatic structure never entered the head of either Aristotle…or the heads of any of the commentators of the next 22 centuries.” Conflict as a precept, Katz writes, resulted from a “major shift in deep-seated feelings concerning the patterns of human experience and…human expectation” toward the perception of existence as “a competitive enterprise.” Hegel’s model of conflicting protagonists representing conflicting ideas helped establish the ruling structure and the very idea of drama; it was then visited retroactively on past dramas.

Another tenet questioned is causality (thoroughly filleted in David Ball’s Backwards & Forwards). Causality—like its opposite, lack of causality—is a worldview, and, like the beginning/middle/end edict, offers a reassuring archetype that flies in the face of all we know. Though still prescribed in many a manual, the causality, inevitability and psychology that imply a stable world no longer reflect our perception of reality, which might be better mirrored by plots with sudden, inexplicable and meaningless catastrophes. And the very idea of action has been called into question, rendering the well-made play, well, absurd.

Through the book, we begin to see beneath the veneer of theory. Katz is uncompromising:

The “craft” that is imposed on playwrights in any period, including our own, is sometimes little more than a translation into critical jargon of the moral, social and psychological pieties of the moment. But they become templates, and any practicing playwright will tell you that—crude or irrelevant or worn thin as they may be—putting together a play that’s said to “work” means squeezing the play’s shape and thought into one of those templates….And vestigial memory shapes those templates too—vestiges of those Ancients—essentially Aristotle’s Poetics sloppily understood but reverenced. They too warp and chain playwriting models and add grossly to their banality. The most harmful “guiding principles” are also the most validated.

What I find deliciously ironic is that if the many misapprehensions preached as gospel were in fact “the truth,” then the play considered by many to be “the best,” would be found wanting, as it adheres to so few of the guiding principles Katz decries. Hamlet, written about more than any other work except the Bible, attracts because of the breaches in causality, paradoxes, inconsistency of character and inexplicitness. It exemplifies what Katz calls “gapping” in “The Actor as Playwright”: unanswered questions are the open spaces in which theatre artists are able to “finish” the play, so no production can be definitive. The inexhaustibility of many plays extends their hole-iness.

For Katz, theories are ways of seeing, and none replicate the experience of a play. But if drama is grasped by something other than the mind, perhaps to “understand” a play is to refuse to pluck out its mystery. We glimpse the profound love Katz has for plays—old, new, well-made or avant-garde. Playwright Richard Greenberg offers a telling anecdote from his student days: “One night, I was sitting with him in the Gypsy (a campus bar). Leon had just come from rehearsing an Artaud piece and was explaining to me, in all seriousness, that Barefoot in the Park would one day be recognized as an American classic. It was pure Leon, and it was a formative experience for me.”

In his book, you can see the sheer breadth of Katz’s eclectic taste also reflected in his favorite movies, from L’Avventura to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. No wonder playwrights value him as a dramaturg as well as a teacher. Playwright Quincy Long noted Katz’s “rather stunning lack of condescension toward [new] plays and the struggling playwrights who wrote them.” Playwright and poet Brighde Mullins explains, “No one else ever gave me the permission slip to write the non-narrative, weird, large, landscape plays that have at their heart language.” A playwright himself, Katz is appreciative and protective of the beating heart of a work, no matter the dish on which it is served.

It should be said that Cleaning Augean Stables could have benefited from some ruthless editing, especially in the first half, which is repetitious. On the other hand, each re-statement adds nuance. Rough patches aside, the book offers the pleasure of engaging with a brilliant mind. It belongs on the shelf next to Bentley, Clurman and Esslin. And above all, it should be required for teachers, to keep us from offering rubrics in the place of rigorous thinking, or encouraging conformity where it might inhibit that unwieldy thing called art.

Susan Jonas heads the Legacy Project, and curates On Her Shoulders:

Ten Centuries of Plays by Women,

at OnHerShoulders.weebly.com.