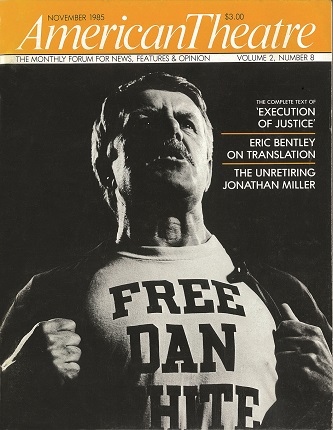

In November 1985, this magazine’s second year of existence, Emily Mann’s Execution of Justice appeared in its pages. It was the first full play text American Theatre had published. In this issue, Will Eno’s The Realistic Joneses makes a round 150. So, you could say the idea stuck.

The magazine has had many play editors, beginning with James Leverett and M. Elizabeth Osborn, whose name now graces an American Theatre Critics Association playwriting award. Among the former TCG staffers who had a hand in selecting scripts were Tony Kushner (whose own Angels in America: Part 1 would later appear in the magazine) and Todd London, now head of New York City’s New Dramatists. From 1995 to 2002, the series was supported by L.A.’s Audrey Skirball–Kenis Theater Projects. Each time this magazine’s publishers have surveyed our readers, an overwhelming majority cite these scripts—which now appear five times a year, and are selected by an interdepartmental committee of TCG staff members—as indispensable.

The magazine has had many play editors, beginning with James Leverett and M. Elizabeth Osborn, whose name now graces an American Theatre Critics Association playwriting award. Among the former TCG staffers who had a hand in selecting scripts were Tony Kushner (whose own Angels in America: Part 1 would later appear in the magazine) and Todd London, now head of New York City’s New Dramatists. From 1995 to 2002, the series was supported by L.A.’s Audrey Skirball–Kenis Theater Projects. Each time this magazine’s publishers have surveyed our readers, an overwhelming majority cite these scripts—which now appear five times a year, and are selected by an interdepartmental committee of TCG staff members—as indispensable.

Since 1994, we’ve provided what we believe is an equally must-have feature: a Q&A with the playwright. Often, the selected interviewer is a kindred artist. Several playwrights have occupied both the “Q” and the “A” chair: This issue’s featured scribe Will Eno, for example, interviewed Edward Albee back when Albee’s Me, Myself and I appeared in our pages in December 2010, soliciting for posterity the great writer’s thoughts on mustaches, kangaroos and the price of socks. Over the years we’ve herded good friends, not-so-secret admirers and protégé-mentor pairings together in a room and turned on the tape recorder. (Yes, until recently, it really was a tape recorder.) Read as a group, these conversations trace a theatrical family tree of influences and inspirations.

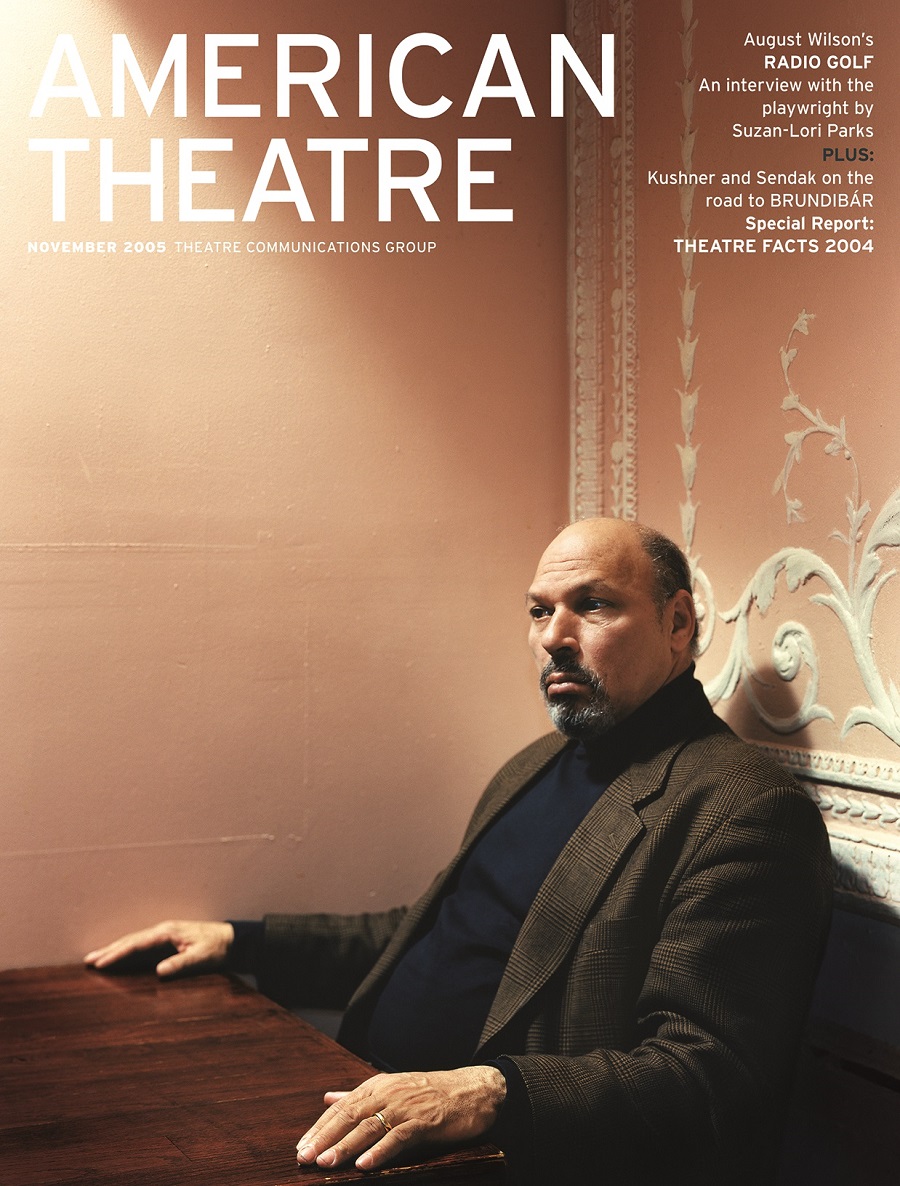

In April 2010, Aftermath’s creators Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen nodded back full circle to AT’s inaugural scribe of the series, Emily Mann, as the catalyst for their own documentary work. When Suzan-Lori Parks spoke with August Wilson, just an hour after she learned he was gravely ill, she took the opportunity to thank him for all his work had meant to her. By the time the culmination of Wilson’s 10-play cycle, Radio Golf, was published in AT’s November 2005 issue, Wilson had died, but their lively, earnest conversation ran alongside it, resonating with the gratitude so much of the field has felt for his accomplishments.

Inspiration is just one of many topics scribes have batted around in AT’s playscript interviews. They’ve held forth on naturalism vs. the avant-garde; on whether writing the “AIDS play” or the “health care play” or the “9/11 play” will pigeonhole or (one almost hopes) doom a work to obsolescence. They’ve detailed, often with still-fresh surprise, the series of events that led to their playwriting vocation, planted seeds of doubt, yielded 11th-hour encouragement.

Occasionally there’s a twist: Naomi Wallace and Donald Margulies had one-acts in the same issue (July/Aug. ’03) and took turns posing questions. Posthumously printed works by Wendy Wasserstein (Third, April ’06) and Romulus Linney (Over Martinis, Driving Somewhere, Sept. ’11) were accompanied by the musings of close collaborators. Christopher Durang interrogated himself—and no softballs, mind—about Betty’s Summer Vacation in December 1999 (“What are you working on now?” “Nothing.” “Nothing? That answer makes me uncomfortable.”). Sam Shepard, it turned out, thought he was on the phone with Esquire (Buried Child, Sept. ’96).

On the spreads that follow is a sampling of this wealth of material. To further celebrate the 150-play milestone, AT will kick off a web-based project on April 1, rolling out many of these full playwright interviews online alongside brand-new audio interviews with their authors. (For a full list of the plays and links to this new material, click here.) Many of the back issues in which these scripts appeared can be purchased from TCG’s customer service department (call 212-609-5900), and many of these writers have also found a permanent home within the catalogue of TCG Books.

All told, these 150 plays represent a stirring spectrum of dramatic voices. They serve as a reminder of the throng of original voices out there writing plays right now, and of the many yet to be discovered in issues to come.

February 1994

February 1994

Pterodactyls by Nicky Silver

Interviewed by Linda MacColl

“It seems to me the difference between a great play and a good play is: A great play is one you have to write and a good play is something that you want to write. And you only have to write every five, seven, ten years, maybe twelve years, maybe once in your life. That’s fine, as long as you know that the plays in between are not great masterpieces, that everything isn’t a symphony, occasionally you write a song.”

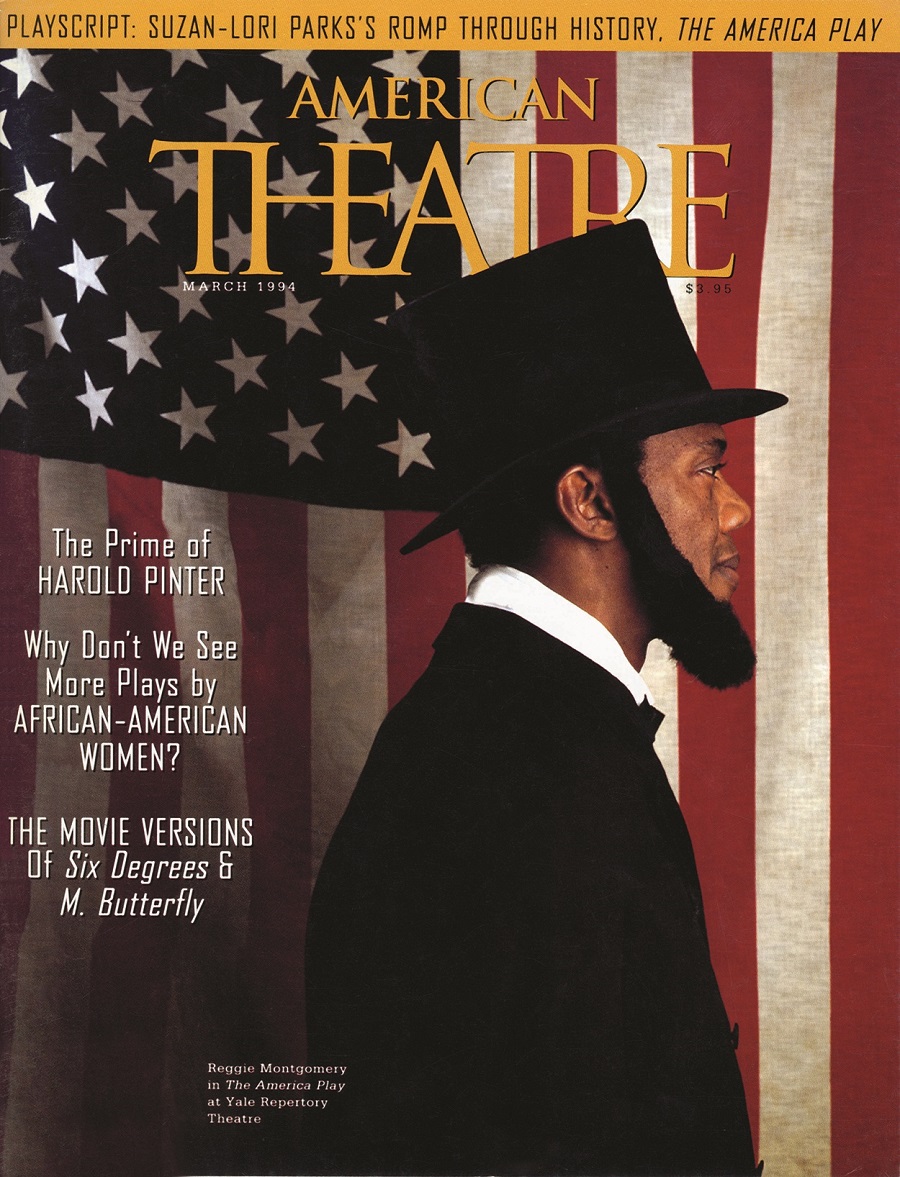

March 1994

The America Play by Suzan-Lori Parks

Interviewed by Michele Pearce

“I take issue with history because it doesn’t serve me—it doesn’t serve me because there isn’t enough of it. In this play, I am simply asking, ‘Where is history?’ because I don’t see it. I don’t see any history out there, so I’ve made some up.”

September 1994

Three Tall Women by Edward Albee

Interviewed by Steven Samuels

“I don’t care so much about staging. If somebody’s going to be onstage, I want them onstage; if they’re going to exit, I want them to leave; if they’re going to be dead, I want them not wandering around. I don’t write down at the first draft of every play exactly how many steps one moves—that’s got to be fairly fluid and make sense. I always tell actors, whenever I direct, you can do anything you want, as long as you end up with exactly what I want.”

November 1995

Santos & Santos by Octavio Solis

Interviewed by Douglas Langworthy

“American culture is so seductive—it really seduces you away from the original culture, the original ideas, the original things that brought you here, and makes you want to immerse yourself in pop culture. Pop culture is in many ways replacing the true original indigenous cultures. It’s so strong that it takes those same symbols, icons and markers that are part of anyone’s original culture and it makes them something else. It can take something from Greece and something from Mexico and make it into a ‘fajita pita.’”

December 1995

Lonely Planet by Steven Dietz

Interviewed by John Istel

“I just received a packet of very kind reviews from an Arizona production of Lonely Planet. In one of them, there was the usual paragraph that says, ‘Sometimes Dietz’s writing goes over the top.’ I’m always relieved by a paragraph like that. I figure I must be doing something right. That’s the only shocking thing left—it’s not nudity, it’s not language—the only shocking thing left, frankly, is sentiment, to use our talents to tell the stories that we feel.”

February 1996

Ballad of Yachiyo by Philip Kan Gotanda

Interviewed by Nina Siegal

“While in the process of writing an earlier draft of Yachiyo, I met David Hockney at an awards ceremony for the Center Theatre Group in Los Angeles. It was right after that that I saw a documentary about how he worked. This was during the period when he was making cubist pictures out of photographs—he would take photographs and put them on a wall, and move them around to achieve different perspectives. I had a very linear story line for this particular play, and I wanted to open the piece up a bit, so I started doing that with my writing.”

July/August 1996

Blues for an Alabama Sky by Pearl Cleage

Interviewed by Douglas Langworthy

“This is the first play in which I’ve had a black woman character who didn’t triumph at the end. In most of my plays, if the woman is weak, she gets stronger; if she’s confused, she achieves clarity. When I got to the end of this play, I realized I was trying to make Angel do something that had not been justified by the characters and by their story, which was to go to Paris. I kept trying to force it, but that doesn’t work. So I had to come to terms with what it meant for me to create a character who doesn’t triumph.”

September 1996

Buried Child by Sam Shepard

Interviewed by Stephanie Coen

“The problem of identity has always interested me. Who in fact are we? Nobody will say we don’t know who we are, because that seems like an adolescent question—we’ve passed beyond existentialism, let’s talk about really important things, like the fucking budget! Give me a break! There are things at stake here—things of the soul and of the heart—and we talk about the budget!”

December 1996

Maricela de la Luz Lights the World by José Rivera

Interviewed by Stephanie Coen

“The play originally was a series of bedtime stories that I told my daughter. The play is about Maricela, but in the bedtime stories my daughter Adena was the hero; every night before going to bed she got to save Los Angeles. It became an ongoing Homeric epic that actually was 20 times longer than the play is. I would tell Adena the story at night, and then the next day she would tell back to me whatever she remembered, and whatever she told me, I would write down—I figured she would remember the juiciest parts.”

February 1997

The Mineola Twins by Paula Vogel

Interviewed by Kathy Sova

“I see The Mineola Twins as a way of figuring out how as siblings we don’t talk to each other. There’s a political schizophrenia that’s dividing us, dividing us in communities, into warring factions, into enraged siblings. To me The Mineola Twins is working toward that moment—even if it’s only in our dreams—that we’ll talk to each other, that we won’t be divided anymore.”

March 1998

Three Days of Rain by Richard Greenberg

Interviewed by Steven Drukman

“Back when I was in Yale, a few of us had a naïve idea that there was such a thing as a commercial comedy. We thought, ‘Let’s write one that will finance the plays we want to write.’ So, my strategy was to figure out what ‘commercial’ buttons got pushed in me, so I could reproduce it. This led me on the most complicated, abstruse path to create the most inaccessible play I had ever written! …Three Days of Rain is, 12 years later, a much-revised version.”

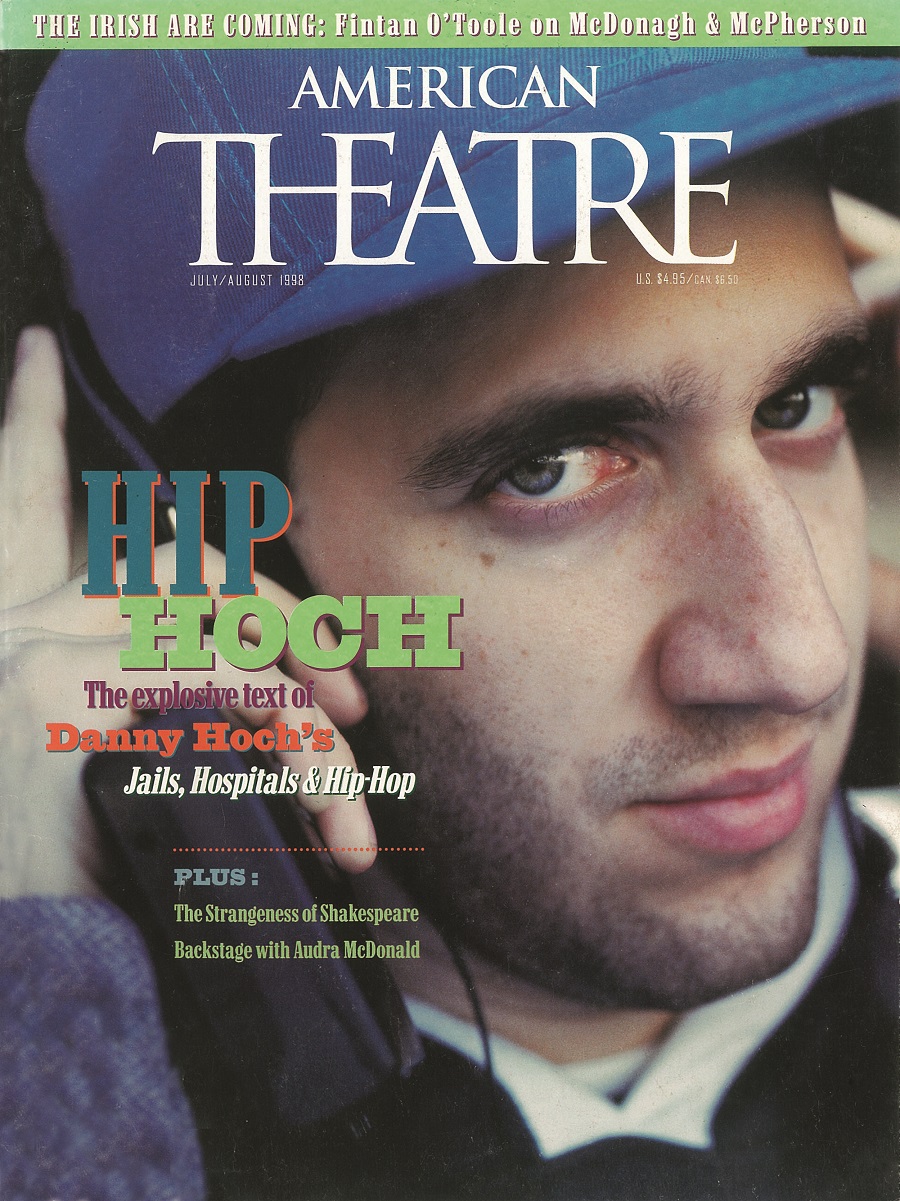

July/August 1998

July/August 1998

Jails, Hospitals and Hip-Hop by Danny Hoch

Interviewed by Wendy Weiner

“These Off-Broadway producers came to see my workshop and said, ‘We’re going to spend $300,000 on your show.’ Then, they got back to me with a budget that had $35 tickets. I said, ‘Listen, $35 tickets tell my entire audience they can’t come to the show.’ They said, ‘We know how you feel about young people, so we’ll have some special matinees where you let young people come.’ I said, ‘No, young people are not gonna come to any special matinees. Young people deserve to be there every night with everybody else. They deserve to dominate my audience.’ So, the producers said, ‘Oh, but don’t worry, we’re gonna spend $90,000 on New York Times ads, so you’ll get people to pay $35,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, but what people? Not my people. Not the people on my block. Not my fucking generation.’ So, I fired them, and then I had zero dollars.”

February 2001

Middle Finger by Han Ong

Interviewed by Lenora Inez Brown

“The idea of exploding the play’s structure was an exciting one, but the more I thought about the boys’ voices the more I thought they would thrive in a naturalistic setting. This may not be perceived to be as adventuresome or as difficult as avant-garde work, but it is in fact more difficult. That was the minor epiphany I had while watching run-throughs of this play. If I told this story in an avant-garde style, there would be no rules, a sense that anything goes, and the boys would have nothing to chafe against.”

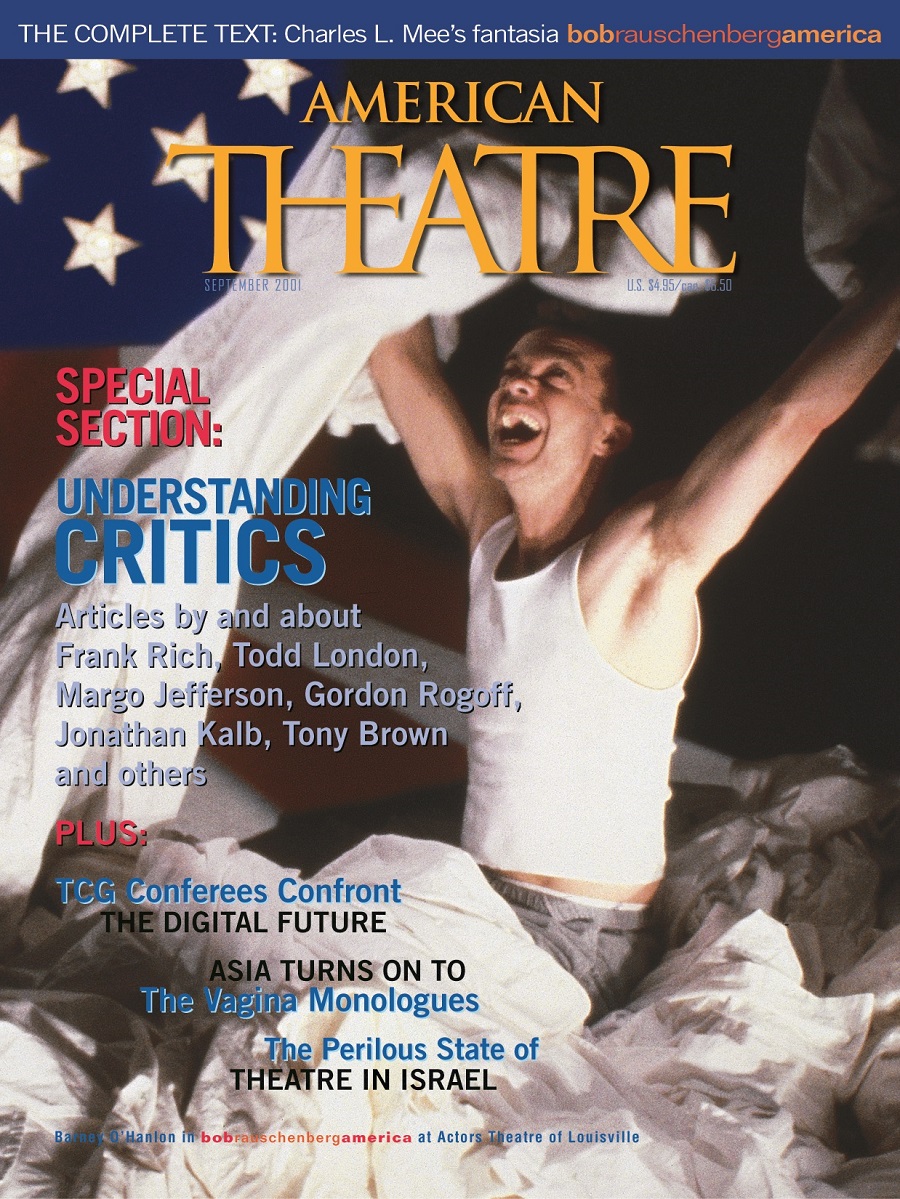

September 2001

bobrauschenbergamerica by Charles L. Mee

Interviewed by Celia Wren

“I’ve been influenced by Rauschenberg for years—my first job was on an art magazine, Horizon—so finally I just decided to acknowledge it. Everybody today is a Rauschenbergian, whether they know it or not. You can read the story of the 20th century’s second half as a project to embrace a broader definition of an acceptable human being—a project to be inclusive of races, genders, sexual orientations, tastes, inclinations, and to put those things at the center of art. Rauschenberg was there first. He is who we would like to be as Americans at our best, with this spirit of egalitarianism and openness to life.”

July/August 2002

A.M. Sunday by Jerome Hairston

Interviewed by Lenora Inez Brown

“I’m attracted to [Tennessee] Williams’s fragile people who express grand emotions with poetic, theatrical language. Through him I began to notice the difference between theatrical language and everyday speech. Then I began to overwrite. When I discovered Pinter, I found that it’s possible to write the same emotional journey with silence or pauses. But in Pinter’s plays the characters are emotionally cold. Williams’s characters have so much heart, which is their Achilles’ heel. So I tried to create a hybrid of these character types in A.M. Sunday—people on the brink of collapse speaking in a terse manner.”

April 2004

Pyretown by John Belluso

Interviewed by Victoria Lewis

“It seems nonsensical to me that I would not write about disability. Because I am in a wheelchair, being disabled affects me every moment. I also take a great deal of pride in the fact that I am a member of a wonderful community of disabled citizens who are part of a civil rights movement. It’s about turning the old model on its head—taking what is seen as illness and turning it into an identity about which one can be proud. That’s part of the larger project of my work. And I think disability is interesting in the sense that it is both a specific and a universal experience, in that anyone who has a body either can become a member or will become a member at some point in their life. The boundaries of disability are porous.”

November 2004

The Clean House by Sarah Ruhl

Interviewed by Pamela Renner

“I’ll be in the middle of a project and my room will be extremely chaotic, and then, before I start a new project, everything has to be restored to order. I think it’s something about keeping entropy at bay. Cleaning is emotional surgery. I was so interested to hear that the classical definition of surgery is: to keep separate that which should remain separate and to conjoin that which should be conjoined. In a way, cleaning is an act of separation. You’re marking time. You’re throwing out old stuff, separating your new magazines from your old ones, your dust from your lemon-scented Pledge.”

February 2005

Mr. Marmalade by Noah Haidle

Interviewed by Christopher Durang

“This being my first produced play, I really didn’t know how [the projected scene headings] would function. I just wrote them because I was amused…. They really helped out with the pace of the play. People would laugh at them. I remember at an audience talkback a guy said, ‘I thought those titles were very good. How did you write them like a four-year-old would write?’ And I was like, really? I tried to write them as a 25-year-old would write them.”

April 2005

The Gods Are Pounding My Head! (AKA Lumberjack Messiah) by Richard Foreman

Interviewed by Young Jean Lee

“I’m finding it harder and harder to feel the justification of writing. I increasingly have the feeling that I’m being pressed tighter and tighter against some big wall, and I don’t know if I’ll be able to break through to the other side. That’s why I announced I was going to stop making the old kinds of plays I’ve been making and do something else. Whether I will really do that 100 percent, who’s to say, but it indicates my desire finally to get through that wall. Maybe that’s what’s interesting about me—that I’m banging my head against this wall that I’ll never get through. If I break through that wall I may completely deteriorate as an artist and be totally non-interesting to anybody.”

November 2005

Radio Golf by August Wilson

Interviewed by Suzan-Lori Parks

“I remember after I wrote Piano Lesson, I was doing an interview with a guy and he says, ‘Well, Mr. Wilson, now that you’ve written these four plays and exhausted the black experience, what are you going to write about next?’ …I just told him I would continue to explore the black experience, whether he thought it was exhausted or not. And then my goal was to prove that it was inexhaustible, that there was no idea that couldn’t be contained by black life.”

February 2006

Electricidad: A Chicano Take on the Tragedy of Electra by Luis Alfaro

Interviewed by Cassandra Johnson

“We did research with active gang members. Interestingly, there’s this image they use that’s the same as the theatre, the happy and sad drama faces, but theirs is: ‘You laugh until you cry’—you live it up until you get caught. Every time I wanted to go farther away from the Greeks, I was brought back to theatre’s origins.”

December 2006

Blue Door by Tanya Barfield

Interviewed by Sarah Hart

“My father was an amateur jazz musician, but I’m not particularly musical. I did a lot of musical research until I felt I could write songs that were authentic to each period. The Yoruba song was tricky, because I don’t speak Yoruba. My dramaturg at Sundance, Chris Sumption, said, ‘Well, I’ll order you a Yoruba dictionary online and we’ll have it FedExed.’ And it came, but it was only Yoruba to English—no English to Yoruba. So I literally read every page of the dictionary to look for the words that I wanted.”

April 2007

The Internationalist by Anne Washburn

Interviewed by Kathryn Walat

“[For the invented language in The Internationalist] there were three rules: First, the sounds would be one-third Romance language, one-third Turkish or Middle Eastern, and one-third Asian—those were the kind of sounds I was pulling from. The second rule was that it should be as uninflected as possible and spoken as rapidly as possible—not like Italian, where you’re singing it. The third rule, which I thought would be sort of elegant, was that there could be little internal rhymes with the vowels. When we were rehearsing it at the Vineyard, I was doing a lot of rewrites with the language. I wrote some lines, and Ken [Rus Schmoll, the director] said, ‘I don’t think that’s the language.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, it’s totally the language—I wrote it!’ He had worked out certain letters that were really rare. The language has almost no c’s or d’s or something. So I guess there are more rules than I know.”

September 2007

Songs of the Dragons Flying to Heaven by Young Jean Lee

Interviewed by Jeffrey M. Jones

“It’s a destructive impulse—I want to destroy the show: make it so bad that it just eats itself, eating away at its own clichés until it becomes complicated and fraught enough to resemble truth…. It’s like when you’re a kid playing with Barbie dolls, and suddenly you pick up the Godzilla figure and knock over the Barbie dream house. It’s this childish, destructive impulse, where you realize that ruining something is going to have the most interesting results.”

December 2007

Scarcity by Lucy Thurber

Interviewed by Kathryn Walat

“I started thinking about the use of the term ‘trash’ when I was at the O’Neill [Theater Center] right out of college, working as an electrician. August Wilson was there with Seven Guitars. When I saw it, I said, ‘Oh, my God, that’s what I want to do.’ I got up the guts to talk to Wilson, and he asked me what I was doing. I said, ‘I write about poor white trash.’ And he said, ‘Are you trash?’ I said, ‘No, no, I’m just using it as a descriptive term to explain that part of the population.’ He said, ‘Again, I ask you, are you trash? Are the people that you grew up with trash? Are the people that you love trash?’ That was a huge, emotional moment for me—where it cracked, this play was born. The language we use about ourselves is important. There is something about having the courage to talk with dignity and trust and faith about these parts of America that are us. Why is the artistic voice only worthy to talk about the privileged?”

March 2008

In the Red and Brown Water by Tarell Alvin McCraney

Interviewed by Christine Dolen

“My dreamscape is so vivid and ambiguous, but also so felt, that I think not drawing from it would be a waste of this incredible resource. I’ve had strange dreams that can make me feel/understand better than think/understand. That’s what I’m trying to do in the theatre space: make people feel/understand, rather than cerebrally, intellectually come to a conclusion. For me, that visceral part of theatre is important. I would be silly to leave that out. As far as the power of dreams, they’ve conflated my thoughts with feelings and fears and made those into one thing. They’ve already done a lot of the work that I would have had to do on a conscious level.”

September 2008

Stunning by David Adjmi

Interviewed by Marian Seldes

“I moved back to New York without a cent, and my mother—God bless her—let me stay at the house I was raised in, in Midwood in Brooklyn. So I was there again, seeing all these people I had sort of been running away from for years, trying to reinvent myself as another person. I thought, ‘Oh, my God. This is profoundly familiar to me.’ I just began writing about them as a canard, in a way, as a joke. I thought it was going to be a silly play for myself. My mother had this empty garage, and I thought, ‘Well, maybe I can clean it out and we can get some flashlights and I’ll put this play on with my aunts and my uncles or something.’ I had no idea that anyone would ever produce it or understand the weird shibboleths and idioms of this [Syrian Sephardic Jewish] culture. I’d always felt I should hide it…. I don’t think I could have written this play had I known that it would actually get seen.”

September 2009

People without History by Richard Maxwell

Interviewed by Elizabeth LeCompte

“You ask somebody who’s coming from a more traditional acting background ‘Where are we?’ and they’ll say, ‘My character is in the kitchen of a commissary. This is where the play takes place.’ Whereas most of the people I have worked with before will say, ‘We’re in Liz’s loft, and we’re here because that’s where the play is happening.’ …How do you reconcile those two? You don’t have to. You can have one foot in one and one foot in the other. But I see a lot of energy put into denying the Liz’s loft part. That has never sat well with me. You don’t have to help the audience pretend we’re somewhere else.”

July/August 2010

The Aliens by Annie Baker

Interviewed by Stuart Miller

“The dream—the dream of what naturalism could be if we let it out of its creepy, pseudo-intellectual, watered-down, lame-o Off-Broadway cage—kept haunting me. Because the way people really talk is so strange. If you transcribe a conversation, it sounds nothing like the so-called naturalistic plays they put up at most big nonprofits. If anything, it sounds more like the writing of Mac Wellman and Richard Maxwell and Anne Washburn, people who are still considered pretty experimental and ‘downtown.’ So at some point in 2007 I decided that I was going to try to write the kind of naturalistic play that I wanted to see, a naturalistic play that paid such insane attention to everyday detail that everyday detail would become defamiliarized and incredibly strange. Like standing really close to an Impressionist painting and just staring at the blobs of paint.”

September 2010

The Train Driver by Athol Fugard

Interviewed by Susan Hilferty

“All that happens to Roelf Visagie in the course of the play encapsulates the journey I have made myself in trying to deal with my legacy of racial prejudice. It is, in essence, a final statement for me—about my relationship to the South Africa I have loved all my life, cursed at a couple of times, but loved, certainly loved. South Africa has taught me all I know about loving, just as it’s taught me all I know about hating. Fortunately, after dealing with all the hate and blindness and ignorance, what really stays with me now is the legacy of love.”

February 2011

Detroit by Lisa D’Amour

Interviewed by Polly Carl

“[Detroit] touches on a panic I feel in a certain middle-class to upper-middle-class United States right now. There’s a feeling that the things we thought were solid—whether it be a house or a job or an economy—are actually more like Jell-O. This can result in hardship, but it can also result in a call-to-action to reinvent yourself, to figure out what you really want and need—who you really are—rather than being ruled by messages (media or otherwise) that have been thrown at you since you were born.”

December 2011

The Ashes by Thomas Bradshaw

Interviewed by Young Jean Lee

“I’m honestly a bit disturbed by this idea of sympathetic characters. I don’t understand why this is something we aspire to. Audiences can identify with all kinds of characters, not just ones constructed to pull at their heartstrings. They might be able to relate more to unsympathetic characters.”

February 2012

Sons of the Prophet by Stephen Karam

Interviewed by Jon Robin Baitz

“One area where I didn’t budge (but thought long and hard about): telling a story about two gay brothers. Some advised I consider making at least one of them straight. I stuck with my gut—but it wasn’t some noble decision. I just realized the heartbeat of the play doesn’t revolve around the brothers’ sexuality, so I felt sure that people who dislike the play would still dislike it even if I switched their sexuality. I’ve heard gay writers on occasion talk about doing the opposite—defending their decision to write mostly straight protagonists because they want to reach the largest possible audience. But that thinking is outdated, right? I mean, I’m moved by straight characters all the time. The Three Sisters moves me every time—and I’ve never once thought ‘If only Masha or Olga were a little lez, I might have an in to this narrative….’ So I just trusted that straight audiences could relate to a family with two gay siblings.”

September 2012

Pilgrims Musa and Sheri in the New World by Yussef El Guindi

Interviewed by Torange Yeghiazarian

“In my day-to-day life, I don’t have ‘ethnic’ moments. I don’t, as some theatre seasons suggest, live a ‘mainstream’ (European-American) life, devoid of the multiplicity of races and tongues, and then have that one ethnic experience before returning to my color-deprived, mainstream life. This country is so very rich. Its richness lies in that wonderful mix. I write what I live. I stage the multiplicity of voices from different backgrounds that I hear and see every day around me.”