Each month, American Theatre goes behind the scenes of the design process of one particular production, getting into the heads of the creative team. This month is Aida, from Theater Latté Da and Hennepin Theatre Trust.

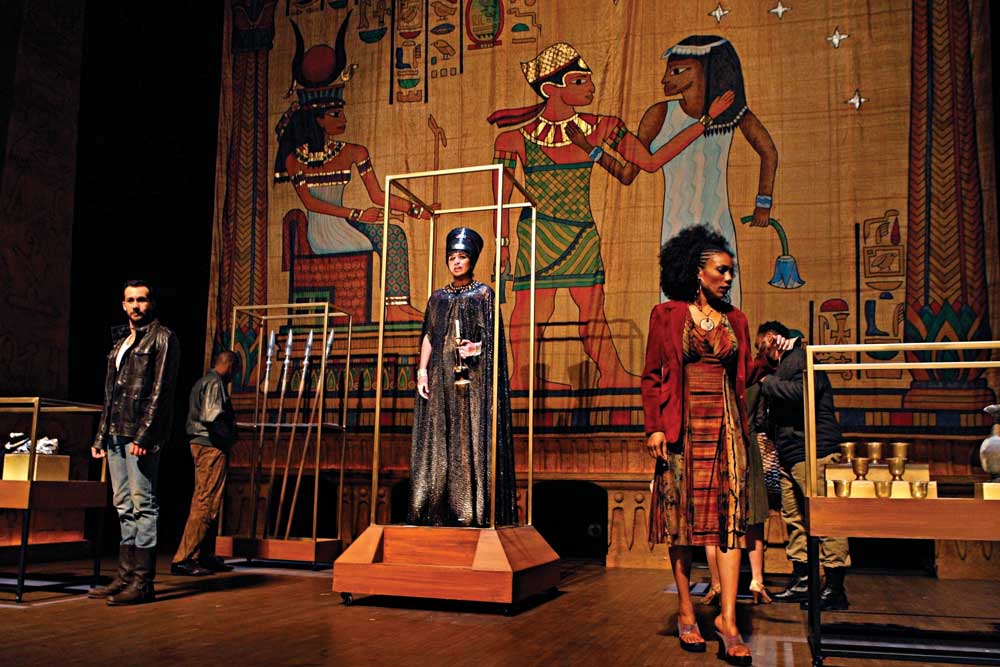

Peter Rothstein, DIRECTION: One thing I loved about the Broadway production of Aida was that it began and ended in the Egyptian wing of a modern museum. There was something responsible about that framing device because Aida, the musical and the opera, was written from a relatively modern Western gaze. So I thought, “What if we took it further and the museum rearticulated itself throughout?” The exhibit pedestals [pictured above] became a way to transport props and artifacts on and offstage. The character of Pharaoh was a sculpture, an artifact, with a disembodied voice. For the final scene where Aida and Radames are buried alive, a stream of sand fell from above into a glass display case. I told the designers that at all times I wanted one foot in ancient Egypt, one in the modern museum and one in the world of rock-and-roll. It needed to look and feel as though a rock band was telling this story. So the microphone became a symbol of power, a weapon of manipulation. The Egyptian characters would step up to a mike for a moment or a song, while Aida and her fellow Nubians were given more organic means to express themselves.

Joel Sass, SET DESIGN: The venue for the show—the Pantages Theatre, a restored 1908 vaudeville house with very little wing space—was a big design influence. Any scenic architecture needed to be stationary, but still capable of evoking different moods. Just out of frame of the above photo, there are two 20-foot obelisks that were painted and textured to look like carved sandstone, but we made them out of a material that could be lit from within. During the big rock-and-roll moments, they would pulse with strobe lights or blaze with various colors. We placed all of the scenes in the show within the context of the exhibit. A series of rolling museum cases and pedestals were fitted with recessed lighting powered by batteries and run with remote dimmers—they exhibited artifacts and delivered props. For instance, that central platform [above] sometimes held a human figure, a throne, or objects for the banquet scenes. One thing that Peter and I were excited about was keeping the band on view at all times. So behind that big painted Egyptian mural, which implied the relationship between the three main characters, there was a five-member rock band, contained in a 16-foot-tall pyramid structure made of gold-painted lighting truss.

Ellen Roeder, COSTUME DESIGN: My partner Lyle Jackson and I went with the clothing of today but struggled with how to give it a Nubian and Egyptian feel. We tackled that challenge via color palette and clothing silhouette. The Nubian palette was earthy with gold, brown and rust. Radames [far left] kept his blue jeans and boots on the entire show. Aida’s robe [above] was made of batik fabric with feathers and beads to create that African feel. Even though Aida is a slave, she’s still a princess and remains true to herself, so we kept her in that dress throughout the entire show—a knit print in a Nubian palette with brown, gold and a little green. Lyle and I were worried about it being too strong and thought about giving her costume changes, but we decided to stick with it. This show was a constant struggle between “Are we doing enough?” and “Have we gone too far?”

Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida ran at the Pantages Theatre in Minneapolis Jan. 3–27, in a co-production between Theater Latté Da and Hennepin Theatre Trust. The production featured direction by Peter Rothstein; music by Elton John; lyrics by Tim Rice; book by Linda Woolverton, Robert Falls and David Henry Hwang; musical direction by Jason Hansen; choreography by Michael Matthew Ferrell; set design by Joel Sass; costume design by Tulle & Dye (Ellen Roeder and Lyle Jackson); lighting design by Marcus Dilliard; and sound design by Sean Healey.