One day last October, a group of actors and stage crew were on their way from Anchorage to perform a preview of a new play in a remote village in the interior of Alaska when they received shocking news. A 21-year-old Native man in Galena on the Yukon River, where they were going, had killed himself the night before.

The play they were scheduled to perform just two days later, The Winter Bear, by Fairbanks playwright Anne Hanley, presents the character of a young Native man who’s thinking of taking his own life, while the central character is based on an actual Galena resident, a respected village elder who fathered almost 20 children, including three sons who committed suicide.

Naturally, the troupe wondered as they waited to fly from Fairbanks to Galena: Should they go through with the performance?

Cyrano’s Theatre Company, the small Anchorage-based nonprofit behind the Winter Bear production, has often stuck its neck out in its 15-plus years. CTC’s founders, Jerry and Sandy Harper, had set their course from the first to perform an eclectic variety of plays in a small storefront theatre they created out of a former police substation. More important, the Harpers decided to perform shows regularly and with the highest quality a lean budget allowed. They would make a strong commitment to local theatre artists, including plays by Alaskan authors. Moreover, the company would actually pay everyone involved—if only, in most cases, a stipend of $250 for four performances a week over a three-to-five-week run.

“To nurture and cultivate Alaska theatre artists—that’s the mission statement. We have done that,” says Sandy Harper, who turned 70 last year, and who has run the company as artistic director and producer since her husband’s death in 2005. “Those are our core values, as opposed to making money. We’re not choosing commercially viable theatre.”

The Winter Bear was largely in that tradition—locally created and locally relevant. Yet, following on the heels of Tony Kushner’s Caroline, or Change, produced by CTC six months earlier, it broke the company mold to become one of the most expensive productions in its history. Harper and playwright Hanley both won grants from a local philanthropic organization, including a travel grant named for the Harpers and another that required a match in money or in-kind donations or both. Having the funds meant spending them, says Harper, and so the company spent comparatively lavishly.

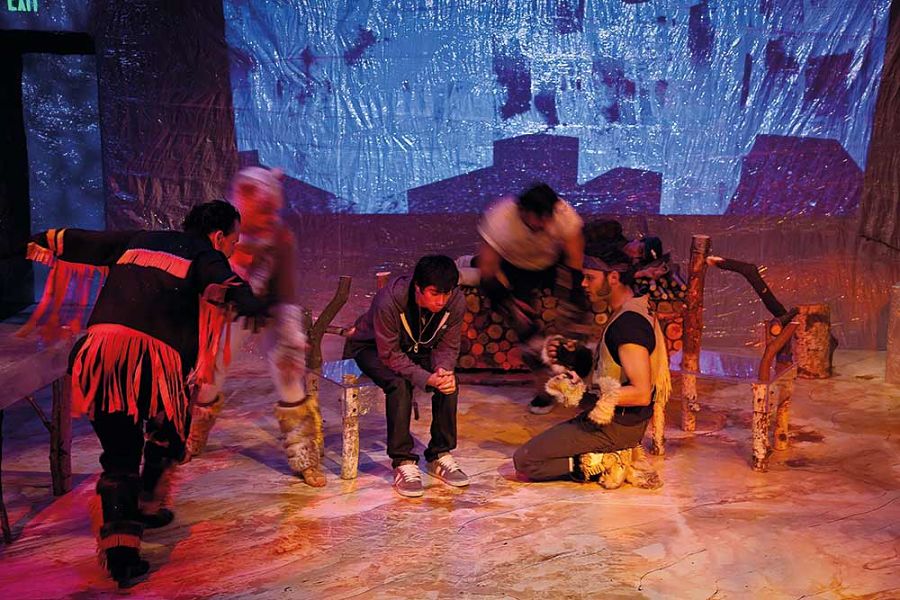

“We were trying to honor the playwright’s vision,” which meant keeping the work as indigenous as possible, says Harper. It was important, for example, to cast as many Native performers as possible, and it was critical to have it be seen by Alaska Natives. So Harper recruited two stage-and-screen actors with Alaska Native roots—Brian Wescott from Los Angeles and Irene Bedard from New York—to play key characters, Galena elder Sidney Huntington and his fictional granddaughter. (The cast also included a 16-year-old Native Youth Olympian raised in Anchorage, who’d never before appeared in a play, in the role of the suicidal young man.)

To helm the play, Harper turned to San Francisco director and dramaturg Jayne Wenger, who had guided an Anchorage writer for a CTC production 18 months earlier. Wenger already was working as Hanley’s dramaturg and eagerly agreed to direct. On Hanley’s suggestion, Harper recruited a New England digital artist for the play’s video projections. The rest of the eight-person cast and remaining design team, including an accomplished Anchorage sculptor for the set and an award-winning Native artist for costume design, were all locals.

Harper booked the show’s world premiere in Anchorage from late October into November, Alaska Native Heritage Month. It would be followed by yet another freshly written work, by an up-and-coming local Native playwright.

The primary venue for CTC shows is Cyrano’s Off-Center Playhouse, a 90-seat thrust stage in one of Anchorage’s oldest buildings, at the corner of Fourth Avenue and D Street in the downtown heart of Alaska’s largest city, home to 290,000. The Harpers, who met as actors in L.A. in the 1960s, relocated from Seattle to Anchorage in the late 1980s to take over active management of an apartment building Jerry had inherited. The Harpers converted adjacent storefronts in the building into a café and bookstore, Cyrano’s Crepes & Books, and Sandy ran it as a kind of literary salon. They opened the playhouse in March 1992 after the Anchorage Police Department decided not to renew its lease of the one-story corner segment of the building and after Jerry had recovered from a benign brain tumor and Sandy from breast cancer. In the early years they shared the space with other groups, then in 1995 incorporated as Eccentric Theatre Co. (later renamed CTC).

CTC plays have occasionally moved to other Alaska venues, most often to Valdez on Prince William Sound, where annually the company has mounted a production for the Last Frontier Theatre Conference. For this year, the conference’s 19th, The Winter Bear will be a featured performance.

“They are on the evening schedule every year because of the quality of their work and their commitment to new plays,” says playwright and producer Dawson Moore, head of the Prince William Sound Community College theatre program and coordinator of the conference. “By far, no company has been as consistently involved as Cyrano’s.”

Sandy Harper’s “m.o.,” as she calls it, is to collaborate with other local arts groups whenever possible and use whatever promotional tie-ins emerge from the material. For example, CTC plans to produce a play in 2012 by its resident playwright, Dick Reichman, about the 19th-century Austrian composer Anton Bruckner. Harper has been urging the conductor of the Anchorage Symphony Orchestra to showcase Bruckner in a program to be played at about the same time.

Harper’s marketing skills and unstoppable—some might say pestering—promotional drive are indeed legendary. Full disclosure: My wife and I used to work for the Anchorage Daily News, the state’s largest paper, and know firsthand what it’s like to be on the receiving end of a Sandy Harper campaign for a feature story or other pre-show publicity. While her manner is unfailingly sweet, friendly and sincere—and her cause nothing short of righteous—the simple fact is that her phone calls and e-mails never stop.

“That’s what I do,” she says. “I want to include the community and be very inclusive with the demographics of the city.” Harper envisoned Caroline, or Change, for example, as a means to link up with Anchorage’s African-American and Jewish populations. And, of course, The Winter Bear and other such Native plays are meant to serve the city’s indigenous population of some 32,000.

“My master’s degree is in human development, and I want to maximize human potential,” she says. “A lot of people to this day get lost in the cracks.”

Sandy Harper is one of the best-connected arts impresarios in the state. When CTC mounted Adam’s Rib in 2006—an adaptation (from the Ruth Gordon/Garson Kanin screenplay) by Anchorage theatre professor, director and frequent CTC collaborator David Edgecombe—the Witness role was filled by a different woman, a local celebrity, each performance. The guest witnesses included a songwriter, a university chancellor, community activists, a former candidate for Alaska governor, a former lieutenant governor, a leading visual arts authority, a former state representative, corporate executives and a surgeon.

Early this past January, the chancellor of the University of Alaska Anchorage phoned Harper to let her know that in May she would be awarded an honorary doctorate—a recognition also bestowed on her husband, in 2004. The black box theatre at the university is named for Jerry Harper, as is a special award for theatre service given at the Valdez theatre conference.

Sandy Harper’s “longevity and level of activity in this tough field alone” justify the highest praise, says Moore, the theatre conference coordinator. “None of us are perfect, but very few have her track record of continued excellence. Cyrano’s seasons have exposed Anchorage audiences to many of the most important scripts in modern drama, as well as classics, as well as local authors.”

“It’s amazing to me they do a play every month,” says Ed Bourgeois, director of public programs at the Alaska Native Heritage Center and a former director of the Anchorage Opera. “As a producer, I know that’s not an easy thing to do. I respect Sandy for mixing traditional theatre with new works. As we all know, new work can be a risky business. The goal is to have a subscription audience trust you enough that you can give them something brand new that they’ve never heard of. That’s where Cyrano’s is at.”

“Another thing that sets her apart is her support of and her mentorship of theatre professionals,” says Catherine Stadem, an Anchorage critic and author of a book-length history of theatre in Anchorage from the city’s founding in 1915 through 2005. “She stays with people and allows them to take chances.”

Moore says he’s grateful for what the Harpers did for him early in his career as a writer for the stage by giving him a two-week run for a one-act comedy he’d written. “Sandy and Jerry were very excited for me to put the show on their stage,” he says. “Nothing was more important to me in my early playwriting days than working in rehearsal on my scripts and seeing how the results played in front of an audience.”

In 2009, Alaska celebrated its 50th anniversary as a state. Sandy Harper saw the milestone as an opportunity to run a year’s worth of shows linked, however tentatively, to Alaskan history and culture. Among the anniversary plays were five new works commissioned from Alaska writers. She gave each a general topic and a scheduled production date. (I happened to be one of those five writers, which makes me living proof that Harper takes bold chances and often relies on her guts alone, because up to that time I had not completed a full-length play.)

“One of our board members said, ‘Don’t you think you should do a little more Neil Simon?’” Harper says of a board discussion about the commissioned works in honor of statehood. “He didn’t think the public would come to see brand-new plays by Alaskan playwrights on Alaskan themes—and five of them. Actually, they did reasonably well.” The five plays as a whole did lose money but not a lot, says Laura Emerson, who served as president of the board for a three-year term that ended in December. At that time, Cyrano’s tickets sold for no more than $17.50. Last year prices topped out at $20 (with a surcharge for musicals), and attendance rose, too. The year 2010 will see CTC in the black for the first time since 2007, says Emerson.

For a new play in 2009 that would show the Native view of statehood, Harper recruited Jack Dalton of Anchorage, whom she and her late husband knew from his unscripted theatrical storytelling but who had never written a play before. Dalton persuaded another Native performance artist, Allison Warden, to join him in writing Time Immemorial. Their play was later performed elsewhere in Alaska and is scheduled for an Equity production by Native Voices at the Autry in Los Angeles in March of next year. When Harper asked Dalton for another play, he penned Assimilation, a stern, raw, tables-are-turned account that received a glowing review from the Anchorage Daily News.

“I wouldn’t be a playwright without the Harpers,” the 38-year-old Dalton says. “I would have never dreamed of going down that road if not for Jerry saying to Sandy, ‘Keep an eye on him,’ and Sandy saying, ‘Why don’t you write a play?’”

During Alaska Native Heritage Month last November, Harper hosted a first-time reading of nine new plays by Native writers, eight of whom had never written for the stage before. The Alaska Native Playwrights Project, supported by a grant from the Ford Foundation, matched each of the nine writers with a mentor who, in almost every case, is a produced Native playwright. Ed Bourgeois coordinated the project.

“The readings were just the first step, an opportunity for new playwrights to hear their words spoken on stage, to see the audience reaction, to have their own reaction,” Bourgeois says. Once the nine plays have been revised, each will be submitted to Native Voices at the Autry, he says. “The impetus to have Cyrano’s be the home for Native theatre in Alaska came from Sandy Harper personally,” Bourgeois notes.

“With Sandy, there’s no ego involved. She wants to do it because it needs to be done,” adds Hanley, the writer of Winter Bear. “She’s unflaggingly optimistic.”

For decades, suicide has been an epidemic for Alaska Native peoples, who have the highest suicide rate of any ethnicity in the United States, according to the Alaska Statewide Suicide Prevention Council. The one bright spot noted in a report issued early this year by the council is that Alaskans appear now to be more willing to talk about the problem than they were, say, 10 years ago.

Hanley, a 64-year-old former Alaska State Writer Laureate, learned that firsthand. She had begun her 15th full-length play to honor the life of Sidney Huntington, a Galena Athabascan in his nineties, author of Shadows on the Koyukuk: An Alaskan Native’s Life Along the River. But in discussions with him, Hanley says, “he opened up the process” by talking about his own sons’ suicides, and she worked the dark theme into the script.

It was Huntington and other villagers who ultimately insisted last October that The Winter Bear go forward in Galena despite the young man’s suicide only days before. Hanley later wrote about the event:

We were afraid that our play, which explores the causes of suicide, would be too raw, that we would be intruding on their grief. Yet we also felt that the timing of our arrival could be perfect to help those in need. They told us to come ahead. No one had any idea what would happen.

We did our play. They listened. They shared their grief with us. We listened. Something in all of us shifted.

Theatre doesn’t offer explanations but we could all feel that in the face of terrible tragedy it does us good to stand up and shout our questions: Why this? Why him? Why here? Why now?

The villagers gave a potlatch in their honor. Sidney Huntington, Hanley wrote, “spoke eloquently about the need to bring the pain of suicide out in the open.”

“No one in the cast will be the same,” Wenger says. “The kids who came to see the play were so emotional.” Afterward, the cast was jammed in the music room with the Galena kids. “We talked about our lives as performance artists. We wanted to do anything we could to help these kids.”

As Sandy Harper begins her eighth decade of life, she says she’s in good health. Any observer can see that her energy level is high. Still, it is perhaps no surprise that as the CTC board begins a classic evolution from a founders’ board to a governing board—and begins to assert more control over financial and other matters—questions about the company’s next chapter are increasingly on the table. Many involved are getting nervous about the costs of some CTC shows.

“She’s had a huge history of successes,” says longtime board member Reichman, whose more than half-dozen works performed at Cyrano’s include one of those triumphs, The Big One, commissioned for the statehood series. A two-act play that dramatizes the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill and its bitter aftermath, The Big One was well received in Anchorage and enjoyed a production in Australia last year just as the BP well was gushing oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Reichman, 65 (and as loyal to Sandy Harper and the legacy of her husband as anyone in Alaska), surmises that pricey productions such as The Winter Bear might be Harper’s way of “pulling out the stops” and living in the present. The tricky question facing Harper and the board now is whether Cyrano’s will be an enduring institution and, if so, what its leadership and financial structure will look like going forward.

Harper’s work in Alaskan theatre thus far is irreplaceable. But what does she think now about the prospect of taking some time to count her laurels, letting the board assume more responsibility, perhaps even preparing to pass the baton? “I don’t know, in my heart of hearts,” she muses. “Was it a fun ride—20 years, a good thing—or do I look to the future?”

Peter Porco is a writer in Anchorage whose play Wind Blown and Dripping, about Dashiell Hammett, received a workshop production at Cyrano’s in January 2010.