When I was writing The Eyes of Babylon, I had no idea I was writing a play. But that’s what it turned out to be. To date I’ve performed the play around the U.S. and in Dublin, and it’s scheduled to open Off Broadway this fall.

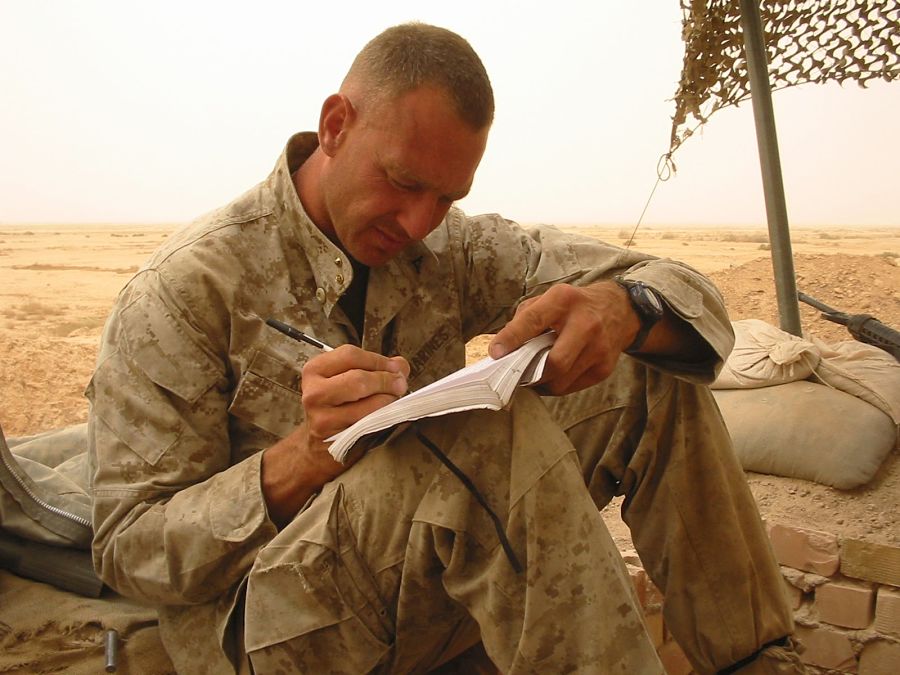

Babylon was developed from my Iraq War journals and parts of letters written from Iraq. At the time I was making those journal entries, I probably would have told you I was writing mostly so that if I was killed over there, my loved ones could have some idea of what I was going through. Now I know that I was more likely writing to some future version of myself.

My time in Iraq was the most intensely spiritual time of my life. Sometimes, after a sleepless night on duty, I would stare into the rising sun and feel like the secrets of the ages had been whispered to me. No matter what the politics and the reality of the American intervention in Iraq, I felt that when I took the face of an Iraqi child into my hands and we looked into each other’s eyes, that child could see my deepest intention: that I had come to this country with an intense desire to help its people. I had heard the stories of Saddam Hussein’s brutality from the Iraqis themselves, and I believed them. But even as I witnessed kindness toward the Iraqis by some of my fellow Marines, I watched brokenhearted as the government, the military and the infrastructure of the country were destroyed. The sickening realization swept over me that I was part of an occupation, not a liberation. As the pieces of the grander scheme fell into place like a puzzle, I fell deeper into despair.

And alongside the kindnesses that some Marines offered Iraqis, others exhibited great cruelty. Cruelty is the thing in life that I abhor most. In no way did it fit into my idea of what a Marine should be.

There was another important component to my spiritual and emotional experience in Iraq: the part that involved my fellow Marines and my sexuality. A lot of the grief I had experienced in life came from growing up gay in a culture mostly hostile toward gay people. Why had I joined the Marine Corps at 34? My short list of answers—a profound belief in representative government, a desire to defend defenseless people, a love for my country—is as true today as when I walked into that recruiting office. As time passes, however, I can see that my own internalized homophobia played a part in that decision: A Marine is the prototype of American masculinity, and if I could find a place in such company, perhaps I would finally be “enough.” In all honesty, while training to become a Marine I accessed parts of myself I never knew were there. But my biggest discovery was that everything I thought I was missing was already there inside me. Ironically, I found that when things got really rough during my training or later on in Iraq, I could actually draw on strengths I had developed surviving the slings and arrows of living as part of an oppressed minority. Not only was being gay not a liability in being a Marine—it proved to be an asset!

In some ways, becoming a Marine felt like the best thing I had ever done. When my fellow Marines welcomed me into the fold and gave me their trust and friendship, I gained things that had eluded me my entire life. My buddies, who were all straight, knew I was gay from early in our friendships. I told them. I had always thought I would be able to play along with “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” until I experienced military life from the inside—and discovered that to be that dishonest about who you really are with someone who is willing to give his life for yours in an instant is despicable and disrespectful. It is as far as can be from the core values of the Marine Corps: honor, courage and commitment. I believe it was because I had been so completely honest with them that these men sought me out as a confidant about what was going on with them in the field.

During my time in Iraq, I began to read my journals to my fellow Marines. It was a form of entertainment for them and a survival mechanism for me. My degree is in theatre, and I’m only truly happy when I am creating. That may sound contradictory to my next admission: I hate the process of writing and struggle with its rigors. Writing, as so many accomplished writers will tell you, is horrible; having written is great. And it was the sharing of the writings with my Marines that was the true joy.

I wrote about the funny things that were happening to us, and the sad things. I wrote about the human part of war: the food, the insects, the heat and the sand. I wrote about masturbation. Reading my journals to the Marines was, I suppose, actually the first incarnation of the play. It was my salvation.

When I got home, I found myself in an impossible crisis of conscience. How I could continue on in the military when I believed that we were being used for such evil purposes, for corporate gain? I discovered what a great many warrior-poets who have gone before me discovered: Wars are generally fought by the poor for the benefit of the rich. I spent the time when I was not on duty writing, praying and meditating. I would envision an explosive white light shooting out from my solar plexus; to me it represented my love for all of humanity, perhaps even the greater form of Love that transcends the word itself. About that time there was a physical manifestation of my vision: After moving tons of shattered tile and marble with my fellow Marines, I hoisted a 400-pound transmission with another Devil Dog and opened a radial hernia in my abdominal wall. I had to be flown home for surgery.

During my recovery at the naval hospital at Camp Pendleton, Calif., I had even more time to think about our occupation of Iraq and about the Bush Administration’s policies. I fell into a deeper depression; suicide began to seem like a real option. I could see how when all was said and done, we were actually making our nation less safe; our military was being badly misused, and I could no longer be a party to it. I called my buddies and told them that before I left the Marines—and did so in a very public way—I wanted them to assure me that they didn’t think I was doing it to avoid going back to Iraq, or because I was somehow not willing to die for them if need be. The response was similar from each of them. It went something like: “Key, if you do this, you’ll be less safe than when we were in Iraq. Somebody will kill you.” I knew they had a point. I was about to speak out against the biggest money-making machine the world has ever known; still, I knew that to die standing up for what I believe in would be far better than to try to live in silence about my opposition to our increasingly imperialistic foreign policy and to the ban on gays serving openly in the military.

I wrote my commanding officer a seven-page letter explaining why I was leaving the Marine Corps. Then I went on a CNN news program and came out of the closet to five million people. If I ever want to go back into the closet, I’ll have to go to another planet.

That interview was equal parts terrifying and liberating. I have never regretted it. The sensitive, creative and queer 12-year-old version of myself, still alive inside me but somehow stunned into silence by cruelty and abuse, lifted his face and bit into the sun that day.

It was about this time that I met Yuval Hadadi, a Manhattan-based stage and film director who was working in Los Angeles, where I was then living. He had grown up in Tel Aviv, was a veteran of the Israeli/Lebanon war of 1982 and was particularly interested in my experience. I said to him what I said to most people: “I don’t really like to talk about it, but if you like, I’ll read to you from my journals.”

As we sat at a coffeehouse and I read to Hadadi, I could sense his connection to the words. Could we meet again for him to hear more? I agreed. It was on our second visit that Hadadi told me that if I would agree to let him direct me, he would stay in L.A. another few months and we would bring the journals to the stage as a solo performance piece.

For the first time in a while, I felt that I had a purpose again. I began to shave the journals down into something resembling a play. Hadadi asked me to cut out everything except what absolutely must be said. I returned with something about the length of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Nicholas Nickleby. Yet every time the director suggested a cut, it felt as though he were proposing to cut an arm off my baby. We fought and flirted our way through six weeks of rehearsals. It was grueling and wonderful.

A small theatre in Hollywood agreed to let us workshop the play on off nights, and for seven months we played there under the agreement that we give every penny of the door receipts to the owners. There was no money for advertising, and some nights the crowds were sparse or non-existent. I felt disheartened, but not ready to quit. I came into a small amount of money and spent it to rent the theatre for six weeks and move the show to weekends. A reviewer from the Los Angeles Times gave us a glowing review—and we closed in L.A. to full houses.

Since that time we’ve had critically acclaimed runs of the play in San Francisco; Durham, N.C.; Boston; Salt Lake City; and Birmingham, Ala., as well as in Ireland at the International Dublin Gay Theatre Festival. I grew up near Birmingham, so that was a particularly meaningful run for me. The Showtime Network made a movie about my story, called Semper Fi: One Marine’s Journey, that includes the play.

One night I was to perform in a community center in Liberty, Ky., and when I arrived there were 300 right-wing Christian protestors there who wanted me to change my politics and my sexuality or get out of Kentucky. They began to pray at me and sing “Amazing Grace” with more percussive zeal than you can imagine. I invited them in to see the play free of charge. To my knowledge, none of them took up my offer; instead, a group of about 30 courageous souls parted the waves of protestors to come in and watch the play. The local hairdresser, who had slipped in the side door, came up to me after the performance in tears. He poured out his heart and told me how he related to my story of having grown up gay in the South. Moments like that make the hard times more than worth it. Closeted gay kids and closeted liberals, military veterans, gay and straight—these people reach out to me, whether or not they identify with my politics or my position on the Iraq War. The play seems to open hearts and minds.

I’ve performed The Eyes of Babylon in left-wing cafés and in a yurt in Big Sur. One of my strangest venues was a big tent in a pasture in Crawford, Tex., right outside the Bush ranch, where a large group of us were protesting the Iraq War. It was there that I met Joan Baez, who had come to lend her support and to sing. Baez has since taught me a great deal about how to be an effective activist and how to use art to speak out about things that are important.

In a way, Babylon has been headed to New York all along. You might say the story began there, on Sept. 11, 2001. Shortly after the terrorist attacks I traveled to New York to see ground zero. I went in dress blues out of respect for the fallen. When the firemen saw me, they took me on a personal tour. At FDNY’s Ten House, across the street from where the towers once stood, they showed me the lockers of men who died that day and took me to the roof so I could see the huge wound in the city and in my nation. “Go do whatever you need to help make sure this doesn’t happen again,” a fireman said to me. I promised that I would.

When I walk onstage in New York this fall, I will not be stepping there alone. With me in my heart will be every sensitive and creative queer kid who was ever made to feel unwelcome because she or he was different. I’ll have with me members of the armed services who will never return to tell their own stories. I’ll be stepping there on behalf of every innocent person who died because of senseless wars, and of every artist who ever dreamed of such a blessing but was never able to see it come to fruition.

Toward the end of The Eyes of Babylon, a monologue, taken from a letter I wrote from Iraq “to my fellow artists and actors back in the States,” has this to say:

Before you take the stage, even to rehearse, honor it for all that it is. Do not cover one blemish with greasepaint, but kneel close to the footlights so that all may see. That thing which you have felt made you ugly, when held courageously in the light, becomes your most beautiful quality. Your grossest liability will be transformed into your chief asset. Let everything you do be for the art and for peace.

You can follow Jeff Key on Twitter.