In Stockholm, a Visceral Blue

Ivo van Hove’s iconoclastic bad-boy status in the U.S. says far more about us—our intractable conservatism, our veneration of naturalism, our exoticizing of foreign fare, and our degraded critical discourse—than about this brainy-yet-feisty director’s revisionist style. “Invasive,” “bold, gripping,” “desperately gimmicky,” “stimulating,” “Eurotrashy”—the paroxysms of delight, petulance and vexation his gutsy productions generate can read like a comedy of irrational gray matter. Depending on the point of view, this emperor’s fashion sense runs the gamut from irresistibly voguish to utterly annoying—if he’s seen to be wearing any clothes at all. Van Hove is not, after all, the only inglourious basterd who leaves visible scars in an effort to bring audiences a fresh appreciation of classics in danger of dying from hardened arteries. The irony is that while he is blessed by controversy here, in Europe van Hove’s unabashed auteurism is very much a mainstream staple. Some observers consider him conservative, even.

In the Netherlands, van Hove has held central and enviable positions in Dutch-Belgian cultural life, as head of Het Zuidelijk Toneel in Eindhoven from 1990 to 2000 and, since 2001, as artistic director and theatre manager of Toneelgroep Amsterdam, that country’s largest repertory theatre. Along with the latter troupe’s regular festival appearances in Hamburg, Stuttgart, Vienna and other European cities, as well as his frequent stints at New York Theatre Workshop (his return is slated for September 2010), van Hove’s world-class reputation can be traced back to his leadership of the annual Holland Festival, at which he programmed international theatre, music, opera and dance from 1997 to 2004.

The strange, fascinating thing about van Hove—why we keep lapping his work up for more effrontery—is that he styles himself as a rebel and an establishment figure. Supported by an exceptionally good actors’ ensemble in the Netherlands and a small community of New York actors in the U.S., van Hove hews close to an aesthetic tradition based on the controlling vision of a star director, what the Germans call Regietheater.

This European preoccupation proves effective in re-interpreting the work of modern dramatists like Charles L. Mee and Tony Kushner. Van Hove’s 2007 bare-staged Angels in America for Toneelgroep Amsterdam, for instance, “was the most literal version of anti-space I’ve seen in the conventional theatre,” says Kushner, who is writing a new play for Toneelgroep Amsterdam. “It threw the entire event on the actors and their performances. There was no attempt to create stage illusion of any sort. The only departure from the play was that the Angel was played by a male actor. You learn immensely new things from whatever is formalistically unfamiliar in his productions.”

On the other hand, van Hove’s classical revivals in New York entice, challenge and astonish for the opposite reason—because his go-for-broke technique creates uncommon stage realities that allow far greater room for the physical, the incongruous, the animalistic and the poetic than U.S. audiences are accustomed to seeing. Through his idea of naturalism in extremis, van Hove rattles our arthritic conventions and disconcerts even some hipsters who argue against slavish reproductions of classical works.

If he is not turning plush playhouses inside out, he is daring actors to take extraordinary liberties. Who wasn’t taken aback by the sound of frantic baby talk and the sight of bruised actors’ bodies in van Hove’s exhumation of Eugene O’Neill’s More Stately Mansions, the director’s 1997 U.S. debut at New York Theatre Workshop? Remember when Blanche’s dive into a claw-footed bathtub in van Hove’s flawed but revelatory A Streetcar Named Desire prompted New York Times critic Ben Brantley to snigger that this 1999 Tennessee Williams revival ought to be dubbed A Bathtub Named Desire? Has Ibsen yet recovered from the taint of the tomato juice that dribbled over the face and skimpy pink satin slip of Elizabeth Marvel’s Hedda Gabler? How many layers of ketchup, chocolate syrup, watermelon, powdered sugar and crushed potato chips metaphorically adhered to actor Bill Camp’s cranky title figure in Molière’s The Misanthrope?

In the service of demonstrating a classical play’s contemporary relevance, there seem to be no sacred cows. In collaboration with his regular production designer Jan Versweyvald, van Hove cultivates and burnishes the impression that he is a magician with a bag of dangerous tricks. To see through the smoke and mirrors, however, it helps to turn away from those European and American classics and instead pay closer attention to his recent spate of flick tricks—a series of screen-to-stage adaptations of 1960s-’70s art-house cult films: John Cassavetes’s Opening Night, Luchino Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers, Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers, and a trio of Antonioni films. A clearer picture emerges when we scrutinize how he conspired to jolly up film pieces that, unlike classical texts, have shorter historical traditions and less scholarly baggage to defy.

Consider the switch of colors van Hove seductively employs in his extreme-theatre production based on Bergman’s script for Cries and Whispers. This co-production of Toneelgroep Amsterdam and deSingel Antwerp inaugurated the Ingmar Bergman International Theatre Festival 2009, which took place this past May at Royal Dramatic Theatre (Dramaten) in Stockholm, where Bergman often worked.

“All my films can be thought of in terms of black and white, except for Cries and Whispers,” Bergman wrote in his book Images: My Life in Film. “In the screenplay, I say that I have thought of the color red as the interior of the soul.” Thanks to a close collaboration with the great cinematographer Sven Nykvist, Bergman saturated his emotionally charged 1972 film about the rapier masochism of sisterhood and family life with a striking color palette made almost exclusively of crimson, black and white (which the Swedish filmmaker associated with the themes of blood, religion and sexual repression).

A bleak yet hypnotic portrayal of pain and suffering, Cries and Whispers takes place inside a tomb-like manor house at the turn of the century. Structured as a gliding series of memories, flashbacks, devastating confrontations and fleshy close-ups that fade out into deep reds, Bergman’s story compels us to observe the frustrated lives and emotional horrors of four women. Agnes, a virginal spinster, is dying of cancer of the womb. Her two unhappily married sisters have come to attend her in her final agony. Callously, they watch and wait, along with Anna, a reliable maid, during the last two days of Agnes’s life.

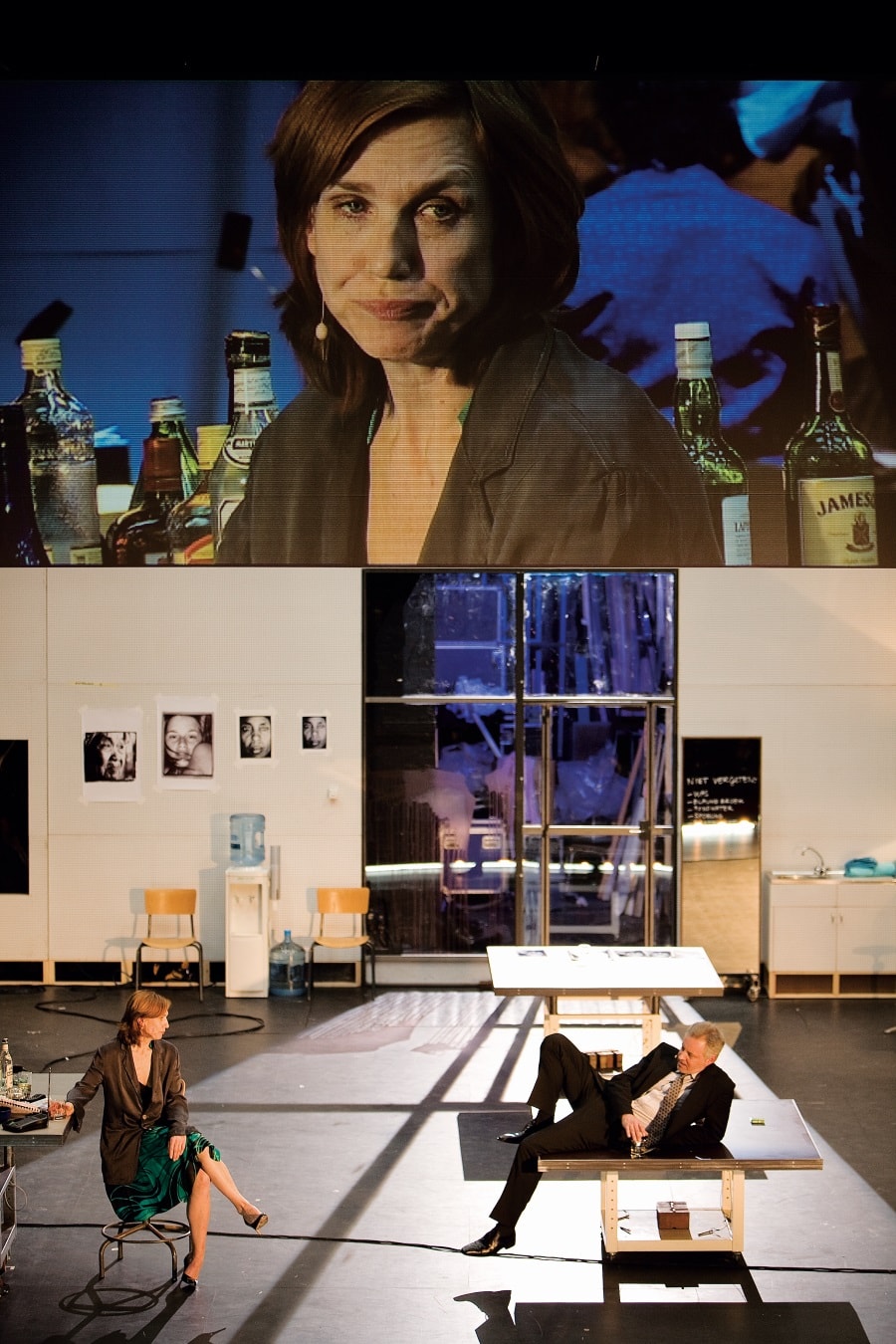

In van Hove, Bergman finds a perfect appositive. Turning away from the strong valences invoked by red, van Hove’s Agnes slathers thick impastos of Yves Klein blue (or IKB, as it is known in art circles) on the glass partitions and white canvases that effortlessly slide in and out of Versweyvald’s layered, open-space set—a sleek coalescence of video workshop, kitchen, living room and austere bedroom. Based on a few lines of description in Bergman’s script (“She has vague artistic ambitions—dabbling in painting…” and “Agnes’s painting is generously colorful and somewhat romantic. Her main subject is flowers”), van Hove re-conceives Agnes as a performance artist whose obsession with her video diaries substitutes for the human affection and sense of community she so desperately hungers for.

This clever and credible extrapolation grows organically out of Bergman’s narrative; it transposes the time frame into the now; and it explains the profusion of techno accessories strewn all over the Dramaten’s stage (a live-video multimedia ethos that similarly marked van Hove’s Hedda Gabler and Misanthrope). In effect, this Agnes dies under the lens of her own camera. At one point, while she writhes in bed, a film image hovers over her, showing a bee pollinating the stamen of a flower (video design is by Brooklyn-based Tal Yarden). It’s an ironic reminder, as the terrible disease consumes her body, that Agnes is surrounded by faithlessness and emotional chill—and that no lover has turned up in her life.

Blue is the color of fidelity and therefore of love. In Cries and Whispers, the chroma blue detaches us emotionally. In tone and content Bergman’s vision of a world of women, set in an earlier era of landed gentry in Sweden, was medieval, private and male-centered; his didactic film, deeply influenced by August Strindberg’s A Dream Play, moves and feels, as the film critic Pauline Kael observes, “like a 19th-century European masterwork in a 20th-century art form.” Van Hove’s Cries and Whispers, by contrast, fuses uninhibited acting, chic-sterile stage design, contemporary attires, loud pop/hard-rock music and live-video footage to create an installation-style atmosphere. Except for replicating a sculptural pose of a dying Agnes that suggests a Pietà, van Hove’s mise-en-scène does not imitate Bergman’s softer film style. His raw and urgent production theatricalizes the jumbled phases of a mourning process; it moves and feels like a 19th-century allegory in a 21st-century hybrid-art form.

And it is most heart-wrenching when it departs from Bergman. The coup de théâtre comes during Agnes’s emotional breakdown, a titanic battle of art against death. Instead of using Bach’s subtle and inconsolable Sarabande from the fifth solo cello suite in the film, van Hove cranks up the techno-music to deafening levels; downplaying the film’s religious symbolism and repressed hysteria, he gives us an Expressionist display of existentialist despair and artistic martyrdom. Actress Chris Nietvelt’s powerful portrayal of Agnes’s dying—her body rolling in blue paint, guts spilling out over the canvas, a tempest of body matter and spasmodic energy—contains echoes of Klein’s Happenings of the ’60s. Yet the confrontation with the truth is hideous and poignant, in-your-face and intense, high-pitched and degrading. Then suddenly a freeze—as the pain soars, her screams stop.

Cries and Whispers is van Hove’s second Bergman show. In his 2005 Scenes from a Marriage in Amsterdam, three pairs of actors (instead of one) simultaneously portrayed the young, middle-aged and older versions of the same couple, whose tumultuous relationship disintegrates. Spectators, who were divided into three groups and escorted into three different compartments, could view each couple’s confrontation in a row—or move freely from room to room. By temperament, therefore, van Hove is more playful, more roguish and more liberated than Bergman, with his closed movie aesthetics and portents that lack an entertainer’s common touch. Van Hove is a mischievous Puck, as opposed to Bergman’s High Priest. Yet, in the final analysis, the Dutch director and the Swedish cineaste have key things in common. In interviews, both have insisted that they have never put on a play against the writer’s intentions. Like Bergman, van Hove regards himself as an interpreter—not a destroyer but a re-creator.

In Amsterdam, a Vast Empty Blue

Blue is the color of the sky. It also refers to the “blue screen” technique that enables background images to be composited behind actors, post-filming. A neutral blue envelops the entire playing area of van Hove’s The Antonioni Project. The stage looks like a giant, empty Hollywood studio. A track for the camera crosses the width of the movie site. Lonely-looking actors wander against the cavernous backdrop, their filmed images relayed to a huge movie screen hanging in the air.

A two-and-a-half-hour intermission-less work, The Antonioni Project intertwines the scenarios of three early 1960s films by the Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni. With a dramaturg’s help, van Hove combinesL’avventura, La notte and L’eclisse into one epic story that culminates into a sociopolitical critique of the alienation of the monied class under modern capitalism and the directionless complacency of bourgeois values. In the play’s second half, all the characters meet on the night of a huge orgy of sex and partying (a clear nod to La notte). A film montage of apocalyptic destruction punctuates the conclusion. In the program, van Hove writes, “The tension between the large-scale (the societal) and the small-scale (the private), and the influence they have upon each other, is the real theme of this trilogy.”

Truth be told, van Hove’s pretty-looking but arid experiment owes a far greater debt to Jean-Luc Godard’s ideological use of cut-ups than it does to Antonioni’s disorienting visual style. Seeing The Antonioni Project in its first tryout performance at the Holland Festival this past June, however, my attention shifted elsewhere: I couldn’t help but notice a bald, lean gentleman holding a camera who kept walking up to the stage, in full view of the public, to take close-up shots of the actors in performance. (Let’s just say our Actors’ Equity would disapprove.)

That man was Jan Versweyveld, van Hove’s life partner and his secret weapon. A lighting and stage designer of unassuming brilliance, Versweyveld realizes the installation-like environment, mood-setting effects and unusual audience positions of their shows, which aim to extend the experience to the venues themselves. In Opening Night at the Brooklyn Academy of Music last year, Versweyveld built a small theatre within the theatre, creating a play within a play with some of the audience sitting on stage and doubling as fictional spectators. In their minimalist update of Jean Cocteau’s 1930 monologue La Voix humaine, he and van Hove imprisoned the great actress Halina Reijn in a box-like, fluorescent-lit room with an actual glass window through which audiences in an industrial warehouse on New York’s Governors Island could scrutinize her. Says Versweyveld, “You really become a voyeur, but in an extreme way.” In fact, the room was soundproof. Like a caged animal, the increasingly suicidal Reijn (in an incredible, unself-conscious, feral performance) was not allowed to hear the audience’s reaction—until she decided to open the window.

Versweyveld studied fine arts in Brussels and at the Royal Academy in Antwerp. Van Hove, born and bred in Flemish Belgium, studied law for years in Antwerp until he decided to turn to the theatre. The two men met during a dance class in the early 1980s. At first they worked on van Hove’s writings and improvised pieces with actors with small theatre groups in Belgium. “We were already on our way to becoming notorious in the theatre world,” Versweyveld recalls. “I didn’t call what we were doing ‘theatre.’ It was more about making a Happening.”

Still, it is a mistake to assume that he and van Hove cut their teeth with nonverbal theatre. Their first major show was Shakespeare’s Macbeth in 1987. The notion of a Happening “helped us to re-view or look differently at classical texts,” Versweyveld explains. “We wanted to make Shakespeare special.” Rather than describe their process of making shows, the designer says, “Sometimes it is easier to say what we don’t want to do. A lot of it is about slicing away or trying to keep the essence. To really create something authentic and universal, I feel we have to start from scratch. Perhaps you have to overcome your own talent or what you have done before. Each time you have to invent warm water again.”

In New York, a Director in Blue Jeans

This past August, a month before the opening of La Voix humaine, van Hove showed up at the TCG offices for an interview.

RANDY GENER: Why have you stayed with one designer throughout your directing career?

IVO VAN HOVE: Because I live with him.

There must be something about the way Jan views the world that informs your work together.

First of all, I believe in total loyalty—that is a basic in my theatre life. Loyalty brings creativity. I also like to work with the same actors. I’ve worked intensely with Halina Reijn now for seven years. I’ve worked with Chris Nietvelt, whom you saw in Cries and Whispers; she played Lady Macbeth in 1987. Coming back to work again with the same people doesn’t bring boredom. Only when it is a bad marriage will it bring boredom. A good marriage brings something new every day. There are crises, conflicts and disagreements, but these lead up to something new and creative. I’ve worked with Jan almost 30 years now, and it is as if we are doing the first show. Every project we’ve worked on is like a child. You don’t treat your children all the same way—that’s fascistic. Every theatre piece wants to be unique. The set, directing, acting and lights have to tell this one story. For me it is not important anymore who directed certain scenes or who came up with the idea of the set. I don’t care about those distinctions. I discuss sets. He discusses directing. Of course, I direct the actors; I have the final say.

Recently, Toneelgroep Amsterdam productions have traveled to Chicago and Brooklyn. Your Dutch work seems to stand apart from your other directing life here with American actors.

Does it? I cannot judge. The actors in New York have become more familiar. I feel I have a real community of people here. I still have the same attitudes: I don’t like auditions so much. I never block. American actors expect me to block the play. I am not going to do that. You can enter wherever you feel like entering. Of course I make decisions during rehearsals, but without the actors feeling that I am blocking them. The way I work is a growth process. I don’t start with the end results. I always compare it to flying or traveling. When you go from Amsterdam to Moscow, you can do it by car. You can fly for three hours. Maybe you realize you cannot hitchhike. Sometimes the actors end up in Prague. It’s a strange example, I know. But whatever happens, a director has to establish, together with the actors and designers, the journey you are making so that you can end up with a Moscow play.

Having returned to O’Neill frequently, do you feel you have cracked his mystery?

O’Neill is the Shakespeare of America. He was able to write specific characters whom Americans really care about but who are, at the same time, universal. You can play them in Japan, England and Amsterdam—everywhere these plays are understood on a deeper level. Like Shakespeare, who wrote comedies, tragedies and history plays, O’Neill wrote sea plays, chamber plays, chorus-driven works, family dramas; he was able to develop his art using different kinds of styles. That is why I come back to him a lot: I did his More Stately Mansions twice, Mourning Becomes Electra twice, Desire Under the Elms twice, and Moon for the Misbegotten.

I have a very specific take on O’Neill, and it is not psychological. It was difficult at first to bring that off with American actors. I make a much more theatrical show out of his text. Also I treat O’Neill with humor—some critics couldn’t accept that. Joan Macintosh was the catalytic agent who made More Stately Mansions possible for me. She really understood me. Because she was a member of Richard Schechner’s avant-garde collective, she could connect with my extremity. She understood my humor. She understood I wanted the subtext played in the text. I totally love that production even more than the one I did in Europe. I feel that the American actors’ background on O’Neill brought something extra to my take on his work. From then on, I’ve dealt with actors in the same manner. I still demand they learn the text before they come to rehearsal. I give them time to do that. I rehearse in the same way as I do in Europe; the acting work is physical in the same way. I look at what I think the capacities are of an actor and then I try to push his or her limits. Of course, I have had the chance and luck to work with people like Bill Camp (he is a giant, a great theatre actor) and Elizabeth Marvel, who is in the Olympic games of theatre—actors whom I would love to have in my company in Amsterdam.

Another more important reason O’Neill appeals to me is that his work is very personal to him. I cannot know exactly what O’Neill’s personal messages are, but you feel that his work is written with blood and tears. His writing is characterized by a tremendous need. That’s what I search for in an author when I direct—artists who care about the big themes. Therefore, I don’t mind if O’Neill’s texts are too long. Let’s face it: Everything is too long. (Except for Desire Under the Elms, which is too short.) We have to accept the way it is, so I try to get under the skin.

Why are you interested in staging films?

With films, you are dealing with material for the first time, at least from a theatrical point of view. It feels like producing Hamlet for the first time. Doing the film scripts is a much more personal statement about how I collected these movies in my life. When I look at the culture in Holland and in the world, at this moment, I see connections with what Benjamin Barber has written in his book, Consumed: How Markets Corrupt Children, Infantilize Adults and Swallow Citizens Whole. We are all being consumed by the expanding global culture of market forces. That is what interested me in the movies.

I notice that you rarely depart from the text, whether the work is of a classical nature or a film script. Obviously there are cuts, compromises and changes of emphasis. Given your reputation for deconstruction, I find it surprising how faithful you are to writers.

I need structure. I need the basic thing itself. I wouldn’t know where to go. Perhaps that attitude will someday change—you never know. I am not the kind of director who puts the text aside and starts fantasizing images. I am really a text director. The only reference is the text. I do drive everyone crazy, because I question every line and, in an opera, every note. Why is that line there? Why this crescendo there? I want to know the why behind the text. Every text needs an interpretation. It needs to be taken care of. To be looked at. There is not one truth about the text—not one truth. You have to find your own truth.

What is the function of video and multimedia in your productions?

Not all my shows use multimedia. I use them when I can. Greek theatre used masks. At that time, masks were a kind of video that allowed the Greeks to give close-ups. They were a kind of microphone, or horn. Media are the devices we have today. To create a new part, theatre always needs a costume.

Epilogue: A Flashback to Vienna

Suddenly the TV monitor in front of me turned blue. A flurry of activity on the Halle E stage in Vienna’s Museum Quarter indicated that a scene change was happening. I had made myself at home on a dark blue sofa in Versweyveld’s open-plan set. He had transformed the stage into a busy conference center with offices, meeting rooms, make-up spaces, carpeting, buffet tables, bars and media lounges. The guy to my left was reading a magazine. Two friends swapped places to use the Internet. One guy was taking a nap. Some Germans checked out the live snake on the set and then went back to their seats in the auditorium. An announcement declared that we had 95 seconds to move around. Without leaving the stage, I walked up to a blond actor and bought white wine and sandwiches.

It was June 2008 at the Wiener Festwochen. George W. Bush was still the U.S. president. Looking back, I realize that I had been swallowed whole by the grotesque “Real World”-like forces at play in the three Shakespeare plays (Coriolanus, Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra) that constitute van Hove’s six-hour marathon called The Roman Tragedies. I witnessed Coriolanus’s death from a table at the back of the stage. Because of the potted plants obscuring my view of Brutus’s press conference, I watched his famous speech (“I come to praise Caesar, not to bury him”) on the monitors above. The Dutch actors pulled no punches in their raucous portrayals of anchormen, senators, generals, cameramen, businessmen and so forth. The razor-sharp exchanges, petty jealousies, backroom politics and blatant hypocrises seemed not just incredibly real but were also hugely magnified by the cameras and TV screens scattered around me. In this simulacrum, there were no intermissions, but there was an explicit body count. Every so often I was slapped back to my senses when footage of American soldiers in Iraq was shown or a soldier was killed in the play; his body was laid on a slab and projected onto a large screen for all of us to contemplate. I wondered: Can a show such as this be produced or presented on American stages?

Compellingly, The Roman Tragedies used 17 actors (48 participants in all, counting the crew) to stage declarations of war and public debates as global media events that unfolded in our living rooms. The dramatic-installation concept made so much sense that I, as a powerless spectator-citizen both in the world of theatre and in the world of the play, felt deeply implicated in the media’s illusion of closeness and truthfulness, especially in relationship to the centers of so-called democratic government and corporate strength.

Van Hove opens a new production of The Roman Tragedies this month at the Barbican Center in London. This Shakespeare production crystallizes and harmonizes, more than any classic a-la-Hove I’ve seen in the U.S. or in Europe, the twin forces of visual excess and textual fidelity that animate his multidisciplinary theatre—whose capitalist/realist basis blows both hot and cold. If van Hove’s game of upturning the whole aesthetic drawer on the floor means occasionally rendering a play unrecognizable—well, that’s life. Theatre is where the imagination leads us if we listen to a play’s cries and whispers for more life.

On the stage in Vienna, a large red ticker flickered once again to scroll the latest news from the corrupt builders of the modern-day Roman Empire. This, the ticker proclaimed, was the amount of time left before the next murder starts: “One minute until the death of Julius Caesar.”

Randy Gener’s trip to Sweden was made possible by the Swedish Institute and arranged by the Consulate General of Sweden in New York. His Vienna stay was supported by Ernst Aichinger of the Austrian Foreign Ministry.