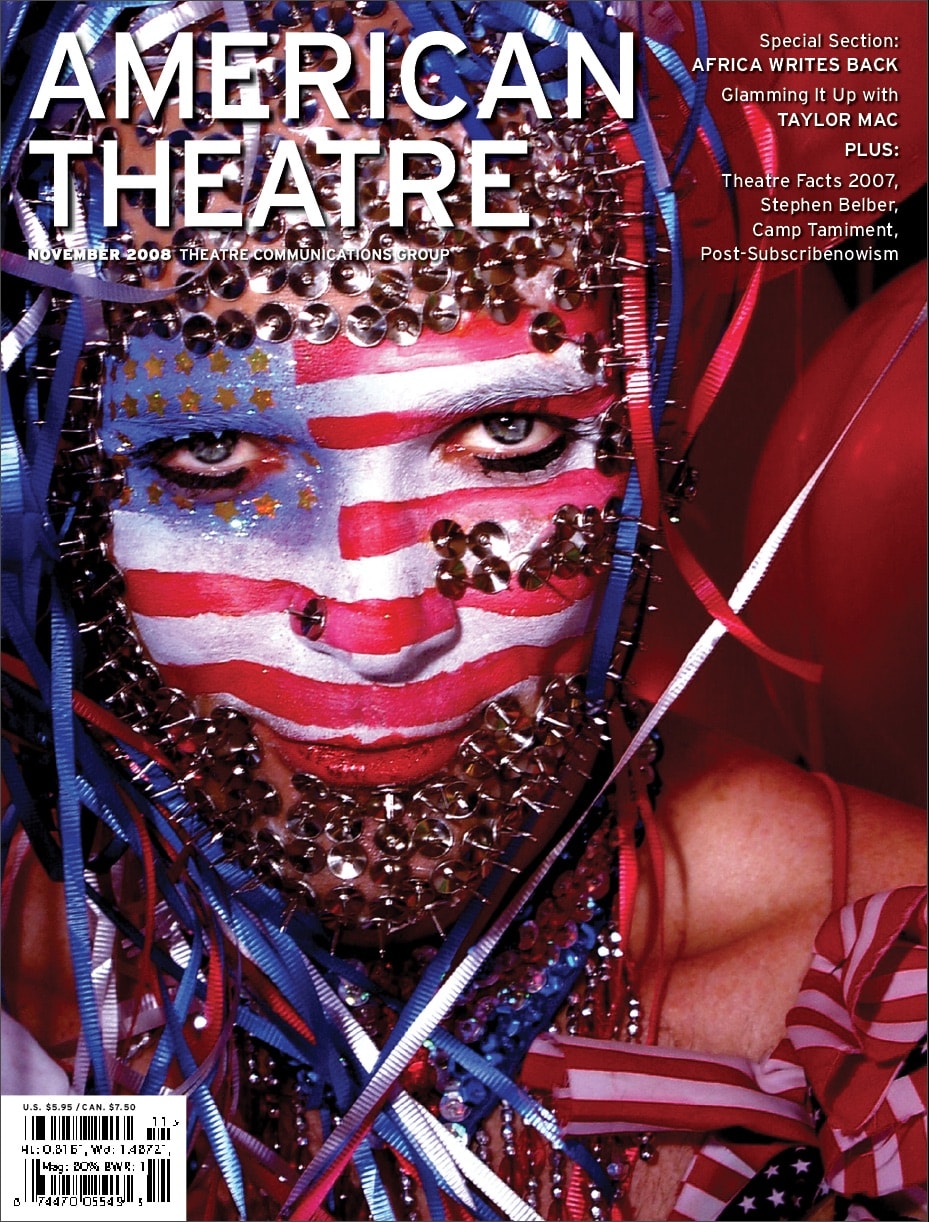

A slender young man in a dress, his face transformed by extravagantly excessive makeup, steps languorously onto the stage. “Hi,” he says in a dry, slightly bemused but welcoming California accent, “my name is Taylor Mac. I’m looking for my light.” Thus begins a story about a boy’s search for his father and a drag theatre artist’s reckoning with self. The play is The Young Ladies Of, and if you don’t yet know the storyteller’s work, you soon will, for Mac is one of this country’s most exciting, heroic and disarmingly funny playwrights. He’s also an actor, performance artist, drag queen, designer, singer and (admittedly) amateur musician.

For the past 16 years, Mac has been cultivating his strange and revelatory art in New York City’s downtown theatre scene at venues such as HERE Arts Center, P.S. 122 and the Public Theater’s Under the Radar festival, as well as at alternative arts venues and festivals abroad (London’s Battersea Arts Centre, Stockholm’s Södra Teatern, Dublin’s Project Arts Centre and the Sydney Opera House). He’s also worked as a guest performer with outsider artist Karen Finley and such groups as the Dresden Dolls and Fischerspooner, among others. What distinguishes Mac’s accomplishment in such plays as Red Tide Blooming (2006), Peace (2007, adapted from Aristophanes and developed with Rachel Chavkin) and The Young Ladies Of the latter premiered last year at HERE, just completed a critically acclaimed run at About Face Theatre in Chicago, and is based on a pile of letters that belonged to his late father, Vietnam War veteran Lt. Robert Mac Bowyer—is the lineage of performance upon which he draws inspiration.

While many U.S. theatre writers, gay and straight, have been seemingly retreating to the confines of the representation of domestic interior worlds, Mac engages in fierce political and personal explorations of theatrical excess, specifically exemplified by drag artists and playwrights working in the realm of camp during the 1970s. There are glimmers in Mac’s work of experimental cult figure Jack Smith (particularly as re-imagined by the late Ron Vawter of the Wooster Group), the gender-bending San Francisco–based troupe the Cockettes, prolific Theatre of the Ridiculous auteur Charles Ludlam and ground-breaking drag artist Ethyl Eichelberger, as well as linguistic and imagistic traces of the 1980s neo-Romantic pop-music movement. Yes, Mac’s work is glam—glam in the sense of playing with the political and spiritual implications of masking and the simultaneous exposure of the eroticized, pan-sexual body. He is in pursuit, like his influential forebears, of the radical openness of possibility.

Graceful, fully felt, handmade yet anti-minimalist, Mac’s work as performer and writer fluidly merges the fantastic with the immediate, the screaming excesses of the body with its sublime stillness, simplicity and beauty. (His popular YouTube video “The Palace of the End” offers a telling glimpse of these qualities.)

As he begins an upcoming tour of the U.S. and abroad with his compendium solo show The Be(A)st of Taylor Mac and The Young Ladies Of, the 35-year-old Mac is emerging from the underground and alternative performance circuit and gaining wider recognition. He is the recipient of the 2008 James Hammerstein Award from Ensemble Studio Theatre and a 2008 Rockefeller MAP Grant, and in 2007 he was simultaneously cited by the Village Voice, Time Out New York and the New York Press as one of New York’s best performers. His new multi-character piece The Lily’s Revenge is playing at HERE through Nov. 22, and he is developing a project with Broadway veteran Mandy Patinkin. I recently sat down with Mac in New York City to talk about what gets him going as an artist and what dreams propel his fierce theatrical visions.

CARIDAD SVICH: How have you found a way to embody in performance such fearless and excessive abandon, but in such thoughtful ways?

TAYLOR MAC: I often joke about how my aesthetic is conceptual, but in fact it is. I was raised in an art school. My mother, Joy Aldrich, started a private art school in the mid-’80s in Stockton, Calif., and once a week, if not more, I took class. We did a lot of collage, and there was a strong emphasis on getting away from viewing art as naturalistic. So from an early age I was creating abstract art and was never expected to draw “inside the lines.” One of the best things my mom taught was problem-solving—we weren’t allowed to use erasers at her school, and instead we had to create something out of the mistake. So I suppose my aesthetic, and even the text and performance style, stems from never erasing. If I’m doing my makeup and some eyeliner smudges—well, that night I’m going to compensate on the rest of my face to work with the smudge. The same applies for when I’m performing. If my voice cracks—well, that means emotionally I’ll be taking a different route; if I forget a lyric, I’ll make some different ones up or use the empty space to ’fess up and expose the flaw. I’m a huge fan of authentic failure on stage. To watch someone honestly fail and be present with that failure is an exceptional present; when it happens in performance, why mess with it? Let ’em have it. On many levels, my aesthetic, performance style and texts are celebrations of imperfection. But more than that, they’re a celebration of variance.

We’re living at a time when the surface images of beauty center on the plasticized reinvention of faces and bodies—there’s freakishness to this manner of re-making of the self, but also an interesting liberation. And then there is the notion of the beautiful freak. As a writer and performer, how do you play with ideas of beauty and its opposite? And with the presentation of ambiguously gendered bodies and personae?

This is where the concept comes in: I take a topic that I want to talk about—say, “the war on terror”—and I write down in two columns all the things I feel about that topic. It turns out I feel angry, sad, scared shitless, oddly hopeful, oddly gleeful (I do find the irony of certain aspects of it hysterically funny at times), chaotic, focused—and the list goes on. Essentially, this is a way to use my conscious and subconscious in tandem. The two kinds of feelings that I put on each list are automatically masculine and feminine (in my experience everything makes me feel inherently masculine and feminine). When I’m done with my list I’ll look around my world and say, “Okay, what around me looks angry, what looks sad, what looks chaotic, focused, pathetic, strong, etc.,” and then I glue it all together.

I’ll continue this technique with my text and my performance style as well. Ultimately what happens is I end up looking, sounding and acting a little bit like everything all at the same time—audiences experience something sweet, ugly, beautiful, disgusting, angry, sarcastic, innocent, fierce, messy, neo-Romantic (if you will), and down the list. They see me as both masculine and feminine. As a result, most everybody can relate to something about what I’m doing, and so I have an in with the audience, even though at first glance it may seem as if I’m alienating them. Also, I’m presenting something they don’t recognize at all, because what I am refuses to be simply one thing, and audiences aren’t familiar with being presented with complexity. So they’re challenged, which I believe is the responsibility of theatre—but I give them permission and a way to take the challenge in. So yes, it is freakish, and “other,” but also recognizable.

People always ask about my character, and my reply is I don’t have one. What you see on stage is me, in a heightened, stage-worthy circumstance. I also often get asked if I’m using the costume as a way to hide something, and my response is always “no.” I feel like the costume is exposing something about myself (and perhaps you, the audience member) that I normally keep at bay. I don’t have a problem with plastic surgery, but I do have a problem with homogeneity. I want us to

embrace variance.

Have you ever felt your work has been censored?

Well, if by censored you mean categorized, then yes. I call myself a theatre artist working in the genre of pastiche, but I also consider the text of what I do to be playwriting. Most people in the industry would not consider me a playwright—they have their understanding of what playwriting is, and it’s based on a strict understanding of Aristotle’s Poetics. I’m a fan of Poetics, and also of the statement I’ve heard from both Jonathan Bolt and Lanford Wilson that it’s a play if the playwright says it’s a play. I associate those artists, institutions and theatrical journalists who categorize everything with evangelical Christians—they’re not interested in metaphor. But I don’t blame anyone. I can get pretty lofty at times as well. There’s a reason for it: Lofty people are protecting a heritage and an investment in craft.

I work at the HERE Arts Center a lot because [artistic director] Kristin Marting is one of the great say-yes-ers. The first time she saw me perform I was dressed as a duck, wearing nothing but yellow paint and a feathered thong, singing a song about how I was addicted to quack. She then cast me in a project of hers in which I played a straight, macho rock star. You say you want to do something and she says “okay” and tries to help you figure out how to do it. That’s what we need more of from our institutions.

Do you ever worry that your work is limited by how it’s labeled and where it’s done or programmed, in terms of who it reaches and why?

I go back and forth about labels. You can describe me as a gay political performer or you could say I’m a poofter princess prancing against the patriarchy. I mean, really—which would you rather see?

In America, my audiences are predominantly white. Last year I performed at the Public Theater in the Under the Radar festival and as I was leaving the theatre five young women, who had stayed after the show, came up to me to talk about it. I was happy and surprised to see them there because they were young black women. I asked what brought them to the show and they told me they were the ushers. This horrifies me. Why are the only minorities at my U.S. performances the people who are working? You can’t tell me it’s because minorities don’t go to the theatre (let alone drag-theatre) when you consider that Tyler Perry, a black drag artist, has been one of the most successful (depending on how you define success) playwrights working in America, and his audiences are almost entirely straight and African American.

One of the reasons theatre is so segregated is because people have grown accustomed to thinking theatrical experiences should be ones familiar to them. Instead of spending all the marketing money on getting the word out to people who are like you, I’d like to figure out a way to get the word out to the people who are not. And instead of saying, “You’re a white gay performer, so if we decide to market to straight black people, what we’ll do is tell them your show is universal, so they won’t be afraid to come,” I’d like marketing people to start challenging audiences to come to this because it is different. How about a marketing strategy that says, “Let’s see you handle this play!” or “Hey, blue-haired lady, this is gonna crack your world open!” In fact, the blue-haired ladies love what I do, because I love them. I’m a “hag-fag”—a gay man that hangs out with eccentric old ladies. Give me the students and the retirees and the McCain voters and all the various colors and persuasions. Let’s have at it. Theatre is a dialogue, and a dialogue is more exciting when you have all different kinds of people and positions entering into it. Audiences understand this and crave it, but they need a little help making the leap. Marketing people need to be the pushers. The Spoleto Festival [in Charleston, S.C.] did a great job of that this year—we had a blast and were sold-out with the whole range of humanity. Ask them how they did it.

I think your work resists definition quite consciously while still honoring a tradition of provocative performance. In what way do you balance your own position as an artist living in your time but speaking through time to the past?

I really do think of myself as a traditionalist. I’m not one of those artists who are out there inventing new forms. I’m a collagist—I take a bunch of established forms and cut and paste them. I suppose that creates a unique way of presenting the work, but the root still comes from the Greeks. Primarily I’m a Fool, in the classical sense. A Fool is a person who speaks truths that others, who do not have such a phantasmagorical aesthetic, are unable to get away with speaking. The Fool is dismissed as insane or is confused with the clown (an entertainer), and so the listener lets his or her guard down. It is when this happens that the Fool can present a truth not usually spoken—and the listener, endeared to the Fool, will actually listen. The Fool is a perpetual outsider. A shaman. A queer. And a queer is not exclusively or merely a homosexual but, as [downtown performer] Penny Arcade says, a person who at an early age was ostracized by society to such a degree that she could never possibly ostracize another human being. The Fool brings an understanding of the social contract because she was born into it, but has the ability to release people from the social contract because she was rejected from it and can see what’s on the outside. The shaman, unlike the priest, who is separate from God, has God within her.

At present we do not celebrate the Fool. At one point she was the King’s companion, the path into the humanity of the court. She emboldened empathy and so had her place in society. Now she is left to hawk her truths in street fairs, basement bars and Off-Off-Off Broadway theatres. I am attempting to get the Fool back into the court, because society is in need of her Fools. If we are to break free of a compassionless policy that supports torture, oppression and greed, our leaders, our government officials and CEOs, our movers and shakers, and the average citizen, need to be reminded of the range of their humanity. They need to see that they have the potential to be more than just male or female, Republican or Democrat, black or white, right or wrong. With a culture intent on demolishing relativism and eradicating the outsider, the Fool, although she still exists, has been reduced to a blemish. And without the Fool as society’s companion, people have turned to the clowns and satirists (Borat and Jon Stewart, to name two), to the priest or reverend, and to the financial broker. These roles show an aspect of humanity—but left on their own to define who we are, they affirm that we are but one thing: divided. A man, a woman, a Christian, a Muslim, an elitist, a commoner. The Fool is proof and a challenge to see that we are many.

But I should say, even though I consider myself more of a Fool than a drag queen, I love being associated with drag. It is a grand tradition. So in the present I’m trying to bring the world of theatre back to a heightened state and inspire audiences to take in the layers.

I’m one of those artists who believes that creative work springs from wounded places in ourselves—that in a sense the act of making art is about discovering the wound anew each time, peeling off the scab, finding the beauty in the places of injury and accident. Where do you find the place of origin for your works, and do they differ?

Dorothy Allison was teaching a writing workshop and she had the class write down a sentence saying the last thing about themselves they would ever want anyone to know. When they were finished she said, “Look at the sentence. That’s the first line of your new novel.” That’s what I try to do when I write—find the thing that I wouldn’t want anyone to know about me and expose it. The trick is to let it be there but keep it from taking over. You do this by allowing it to be as multifaceted as it truly is. Expressing the range of the circumstance is a sure-fire way to keep you away from indulgence and catapult you into something new. I’m not suggesting you have to store up deep dark dirty secrets to be an artist, but I do believe everyone has something they don’t want people to know about them. It might be something as simple as that your arm fat jiggles. Well, wag it, girl, and let it take you through it. The other great thing about being a theatre artist is that after you’ve exposed all the horror in your life and the show is over, you can always say you made it up.

How is your work received outside the U.S.?

I’ve been doing two of my plays, The Be(A)st of Taylor Mac and The Young Ladies Of, all over, and at first I found Europe to be so much more gratifying. But the more I get to all the different places in America, the more I realize it really just depends on the people you’re working with. As long as the theatres have an enthusiastic staff that really cares about the work they’re presenting, I find the audiences become enthusiastic about the work as well. And when that happens, it’s just smooth sailing.

These days I’m working my butt off on the largest endeavor of my life to date—my new play The Lily’s Revenge. As I’ve been obsessed with [mythology expert] Joseph Campbell, the story is a hero’s journey. A potted Lily painfully uproots itself and goes on a quest to destroy the modern tool of oppression—nostalgia (portrayed by the Great Longing Deity). The play takes place during the funerals for Ronald Reagan (he was the great communicator of the nostalgia movement, after all) and uses the countless flowers thrown on his coffin as a metaphor for oppressed and minority people. It’s the second half of my Armageddon series (my play Red Tide Blooming being the first).

The insane part of Lily is that it’s performed over the course of seven hours (including dinner and act breaks) and was inspired by Japanese noh: five plays performed in one day. Lily has more of an Elizabethan structure and is composed of five acts based on the five noh themes of Deity, Ghost-Warrior, Love, Living-Person and Mad-Demon. I’m writing, performing and co-producing, but four different New York City–based ensembles and directors will execute each of the first four acts with me. Furthermore, each ensemble will specialize in a different form of theatre: a musical theatre ensemble, an acting ensemble, a dance ensemble and a puppet ensemble. The final act will be a collaboration by all four companies, incorporating all the previous elements and every performer—at present, 36. If I hadn’t already gone bald, this would certainly do it.

But I’m not alone, and that’s the whole point. An incredible group of people is helping me figure out how to get this work out there—people like Kristin Marting, Morgan Jenness, Mark Russell, Earl Dax, Paul Lucas, Kim Whitener, Nina Mankin and the entire staff of New Dramatists, all of whom have dedicated their lives to helping artists. Without people like them, I’d still be performing in gay basement bars that are really sex clubs. Nothing wrong with that, but I prefer to not have to compete with the blowjobs.

Caridad Svich’s play 12 Ophelias premiered in a site-responsive production by Woodshed Collective at McCarren Park Pool in Brooklyn this summer, with music by the Jones Street Boys. She is the founder of the NoPassport theatre alliance and press, and associate editor of Contemporary Theatre Review.