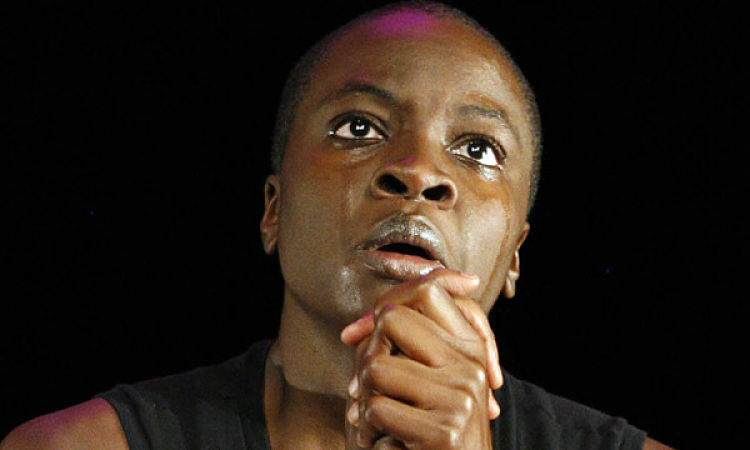

Actors expect the unexpected when a show hits the road. For Nikkole Salter and Danai Gurira, the first stop on the road on this late-April Friday is a makeshift black-box theatre halfway around the world from New York’s Primary Stages, where their Off-Broadway hit In the Continuum got its start in September 2005. And the unexpected, much to the distress of all involved, involves a missing prop, a serving of spicy chicken and a rapidly approaching cue.

Salter and Gurira have brought their two-hander—a vivid, moving, often hilarious set of themes and variations involving an African, an American and the day they both learn they’re pregnant and HIV-positive—to Harare, Zimbabwe, where Gurira grew up and where half of its action is set. (The balance plays out in Salter’s hometown of Los Angeles.)

They’ve had a few days to get past the jet lag. And the extracurricular programming scheduled around their arts-festival booking, including one workshop with a local theatre company and another at a Netherlands-funded skills-building project in the townships outside Harare, has come off without any major catastrophes.

But now the prop bones have gone missing. And without bones for Gurira’s witch-doctor character to throw, the second half of Scene 9 just isn’t going to be the same.

Nice people, it turns out, don’t say “witch doctor.” The word is nganga in Shona, Zimbabwe’s dominant language, and the respectful English equivalent is “traditional healer.” It’s a distinction Gurira and Salter exploit for both laughs and shivers, in a scene that finds Gurira’s character Abigail, a middle-class Shona speaker, checking all options—including the advice of a nganga—as she wrestles with the news of her diagnosis.

“In the States, sometimes people aren’t sure if that really happens,” says Gurira over breakfast at the two actors’ Harare hotel. Not so in Zimbabwe: People know that an ambitious, accomplished professional like Abigail (the character works for Zimbabwe’s national TV network) might well turn to a traditional healer for advice in a desperate situation.

“It’s here—it’s what they experience,” says Gurira, who nevertheless consulted an expert, as well as her own memories, to create the nganga character. She interviewed noted sociologist Gordon Chavunduka, former vice chancellor of the University of Zimbabwe and longtime head of the Zimbabwe National Traditional Healers’ Association—and her uncle, incidentally—to help add depth to the portrayal.

“He isn’t an exact reflection of my uncle,” she cautions. Chavunduka, for one thing, is an herbalist; the nganga Abigail consults in In the Continuum is a spirit medium.

“There’s a difference, and he taught me that,” Gurira says of her uncle. “I talked to him when I was here in 2004, when we were just looking at the play, and I did a couple of rewrites. I humanized [the nganga] a little bit more, made him a bit less one-note, gave him a little more color.”

The homework clearly paid off with the Harare audience, which greeted the nganga scenes with a kind of riotous appreciation—loud, knowing laughter, and copious applause when the character made his exit. One patron even lingered after the curtain calls, wanting to talk with Gurira about the way her performance captured a kind of public-private duality in the nganga character. That enthusiastic response to the nganga underscored the distance—and the surprising similarities—between what Salter and Gurira have come to think of as In the Continuum’s two homes.

“Here, people are talking about the elements of [the nganga’s] reality,” Gurira emphasized, “whereas in the States, people are questioning its reality—they think it’s so separate from them. But, I mean, psychics are on every corner, in New York, anyway—the difference isn’t that large. But sometimes people want to look for large differences.”

There are some undeniable differences, of course, in the worlds occupied by In the Continuum’s characters. Nia, the South-Central teenager played by Salter, struggles with the realities of life in an impoverished urban America, but economic uncertainty defines life across classes in contemporary Zimbabwe. Annual inflation there stands just shy of 1,200 percent annually—a staggering rate, all but unheard of in a nation not at war. Rolling power cuts blanket the capital, reflecting the desperation of a state-run utility that can’t generate enough electricity on its own and can’t afford to import the shortfall. Shortages of food, of fuel, of medicine define the lives of the poor and the prosperous alike—though endemic corruption means that the latter, if they’re willing and able to pay, can work the thriving black market to find what’s critical from day to day.

In the Continuum acknowledges those differences—mourns them and cracks wise about them, in sharply observed vignettes dissecting Zimbabwe’s notoriously authoritarian officialdom and L.A.’s hip-hop culture, in cuttingly funny visits with Harare social climbers and bracing encounters with South-Central matriarchs spouting AIDS conspiracy theories. But ultimately it’s a play about similarities and overlaps and connections. It’s about the terrible commonalities in the lives of two women, half a globe apart, whose fates will be shaped by fears and prejudices and family politics—women whose futures, new millennium or not, hinge almost entirely on the good faith of the men whose faithlessness has put them at risk.

American theatregoers understand that—witness the warm reviews and the show’s 13-week Off-Broadway run—but in some ways, Salter says, the “much more worldly” Zimbabwe audiences were better prepared to appreciate the full range of those differences and those connections.

“I was worried about whether or not they would get it,” she confesses. Specifically, she was anxious about whether the Harare crowd, and by extension subsequent audiences in Cape Town and Johannesburg, South Africa, where In the Continuum will be heading afterward, would pick up on the specifics of the L.A. references. The American characters’ penchant for urban slang, for profanity, for loose diction—those elements, too, had Salter worried that Nia’s story might not connect with African audiences.

But, in the end, Harare theatregoers guffawed as loudly as Manhattanites did at glancing references to five-finger discounts and Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever, government cheese and baby-daddies. If anything, they proved more receptive to the totality of the show than Americans did, Salter says. New Yorkers “understood Abigail’s storyline,” she notes, but never seemed to embrace her the way Zimbabweans embraced Nia. “In the States, we know what power cuts are, but it doesn’t resonate” when Abigail’s newscast rehearsals get cut short by a blackout. In Harare, needless to say, that bit generated howls of laughter and then a storm of applause.

Of course, the arts-festival audience that lined up down the block for Salter and Gurira’s Harare engagements was a pretty sophisticated crowd. In the Continuum was one of nearly 100 acts at the Harare International Festival of the Arts, or HIFA—an against-all-odds phenomenon, launched in 1999 by Zimbabwe-born concert pianist Manuel Bagorro, that somehow manages to draw artists from across Africa and around the world for a six-day celebration of the creative arts amid Harare’s crumbling infrastructure.

French opera singers and German countertenors shared HIFA stages with Indian odissi dancers, the Ivoirian reggae rebel Tiken Jah Fakoly, and the Celebration Choir, a full-throated gospel outfit based at an evangelical megachurch in the affluent Harare suburb of Borrowdale. A concert by Paris-based Afropop star Angélique Kidjo packed the mainstage lawn with a capacity crowd of 5,000-plus. Zimbabwean mbira bands played lineups alongside Basque folk singers, township jazz trios and an Austrian string quartet; a British new-vaudeville troupe worked the sidewalk in front of Harare’s National Gallery.

The theatre track was every bit as diverse and lively. Biro, a widely acclaimed one-man show created by Ugandan-American actor Ntare Mwine (who has appeared on “Alias” and “CSI”), was the other American import. A London outfit staged a production of Patrick Marber’s Closer; two troupes from Masvingo, a dusty mining town near the medieval stone ruins that give Zimbabwe its name, co-produced Edward Albee’s Zoo Story; a Zambian company imagined the career of the first female president of a fictional African nation; Fulbright-funded students from the University of Zimbabwe and California Polytechnic State University created a show about a student lost in Harare’s teeming townships; Theory X, a Harare ensemble recently launched by one of Gurira’s high-school-era friends, presented a loose and lively Shakespeare adaptation called A Midsummer African Dream (Puck—or Puckai—turned out to be a monkey).

All that traffic in and out of the festival’s theatre venues—converted church halls, most of them—made for some rough edges for actors accustomed to working under union rules. “It can get a little guerilla up in there,” Salter jokes. “In the time that’s allotted, and the instruments you have to work with, and the number of shows sharing the space—I mean, come on, something is bound to go wrong,” she laughs. Half an hour before curtain on the afternoon of their first performance, Salter and Gurira, with assistant director Gus Danowski and stage manager Samone B. Weissman, were still focusing lights and reblocking scenes to fit the unfamiliar stage. (They had to do it all over again two days later, because other shows, including Biro, had used the space in the interim.)

Luckily, Salter says, Weissman and Danowski had been with In the Continuum from its early days. “They really hooked us up. Because they know the show so well, we’re able to create the most professional production we can possibly create in any space, the four of us working together.”

Post-Harare and the stops in South Africa, In the Continuum is booked for a U.S. tour beginning at Washington, D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company in August, with dates reaching at least through a June 2007 engagement at Chicago’s Goodman Theatre. Meanwhile Salter and Gurira have already begun groundwork for another joint theatrical project—a commission centering on female freedom fighters in Charles Taylor’s Liberia—and at the invitation of the Oxygen cable network, they’re tossing around ideas for TV shows.

“People are interested in us as writers,” Salter says, “in the ideas we have, the way we collide the subject matter with humanity and humor, so we’ve been asked to try to develop pilots that do the same thing. As an African-American actress, I complain often about the roles that are available even to audition for, and how few of the meaty good ones there actually are, and how hard it is for an unknown to be considered—so to be a part of creating opportunities, that’s a thing I want to do.”

Back at the theatre, Salter is moving steadily through a juicy monologue in which Nia’s cousin Keysha urges Nia not to lose her hold on her basketball-player boyfriend:

It’s not like you got pregnant by some ole, dirty, jerry curl juicy, gold-tooth pimp. We talkin’ Darnell Smith…. Do you know how many girls pokin’ needles in condoms tryin’ta have his baby? And here you sit, on the come-up like Mary pregnant with Jesus, talkin’ ’bout should you have his baby. Have Miss Keysha taught you nothin’?

In the wings, Gurira and an assistant stage manager named Blessing sit hunched over an equally juicy serving of peri-peri chicken, the spicy Portuguese-style specialty from Nando’s, a fast-food chain with an outlet conveniently located just down the block. The prop bones are still missing, see, and Gurira’s nganga needs them in the next scene to interpret the will of the ancestors.

So Gurira and Blessing have ordered takeaway, and now they’re stripping the meat from a three-piece snack as fast as fingers and teeth can manage.

“Me and Blessing, backstage, biting Nando’s chicken off the bones during Nikkole’s scene,” Gurira giggles the next morning at breakfast, as the rest of the In the Continuum gang convulses. “So I came on, and I don’t know, my face might have been greasy. It felt it. And people right near the front could see. They were like, ‘Chiiiicken!’ I just had to go with it. We just went with it. And kept going with it.”

Trey Graham is an arts writer based in Washington, D.C.