The 5th Element

Hip-hop is a worldwide, multi-billion-dollar industry and cultural phenomenon that evokes passionate responses. Many are turned off by its commercial promotion of materialism, misogyny and violence. And, paradoxically, there are those who believe that it is a culture and art form that provides a space for artistic innovation, democratic participation and incisive social analysis—that it is an effective organizing tool for reaching youth and disenfranchised populations.

The scholar Augustin Lao Montes tells us that these two divergent experiences of hip-hop emanate from the way in which hip-hop has been globalized on two parallel yet permeable tracks: One track is the top-down globalization of the marketplace and global capital; it is insidious, omnipresent and incredibly sophisticated. The majority of rap, for example, has been promoted as urban black culture and, ironically, is sold in the suburbs to white consumers.

The scholar Augustin Lao Montes tells us that these two divergent experiences of hip-hop emanate from the way in which hip-hop has been globalized on two parallel yet permeable tracks: One track is the top-down globalization of the marketplace and global capital; it is insidious, omnipresent and incredibly sophisticated. The majority of rap, for example, has been promoted as urban black culture and, ironically, is sold in the suburbs to white consumers.

The second parallel track is the ground-up, grassroots globalization of hip-hop, which has been embraced by communities across the lines of race, class and ethnicity worldwide. This track reminds us of hip-hop’s origins in the Bronx in the early ’70s—where DJs such as Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash created drug- and violence-free havens that celebrated unity. Hip-hop as an art form has given voice to individual expression and community narratives. The conscious roots of these aesthetics have been embraced by hip-hop-generation activists such as the Prison Moratorium Project, the League of Young Voters, Third World Majority, the 21st Century Youth Leadership Project and others who have evolved the civil-rights-era agenda to address myriad issues—including education reform, the prison-industrial complex, labor practices, immigrant rights, the environment and civic participation. British hip-hop theatre artist Jonzi D asserts, “Hip-hop isn’t violent—America’s aggression in the global marketplace is the real violence.”

We all know that other true innovations in art have elicited similar polarized response and controversy: We need only look at the beginnings of modern dance, modern drama or modern art. Perhaps the closest parallel would be to compare hip-hop to a previously unrecognized indigenous American art form. Jazz–once reviled and associated with crime, shady characters and disreputable places—is now appreciated as America’s classical music and a preeminent contribution to world culture. Hip-hop, born on a continuum of African-American culture, is now old enough to have a history and a legacy as its four interdisciplinary elements—MC’ing (or rapping), DJ’ing (or turntablism), B’boying (or breakdancing) and graffiti—influence performance forms, media, visual art, literature, fashion and language.

“Hip-hop theatre,” coined from inside the culture by Brooklyn-based poet Eisa Davis in The Source magazine in March 2000, has come to describe the work of a generation of artists who find themselves defined in a new category of both prospective opportunity and limitation. These artists range from dance-theatre choreographers like Rennie Harris, who heads Puremovement of Philadelphia, and the New York City-based duo Rokafella and Kwikstep, founders of Full Circle Productions; to ensemble artists such as Universes and I Was Born With Two Tongues; to solo artists, including Danny Hoch, Sarah Jones, Will Power, Aya de Leon, Caridad de la Luz, Marc Bamuthi Joseph, Teo Castellanos and Mariposa; to playwrights like Ben Snyder, Kris Diaz, Eisa Davis, Chad Boseman, Candido Tirado and Kamilah Forbes.

These artists range widely in their response to the term. Hoch and Forbes, for example, are at the center of defining and promoting the genre as the co-artistic directors of NYC’s Hip-Hop Theater Festival, which has produced highly successful satellite festivals in San Francisco and Washington, D.C. Forbes talks about her beginnings as an MC; it was her involvement with and love of language that led her to study Shakespeare at Oxford. But it was her longing for hip-hop’s audience that compelled her to forge a new form, “hip-hop theatre.” As an MC, actor and playwright, she contends hip-hop demands heightened listening because of its compression of language and complex rhyme schemes—not unlike Shakespeare.

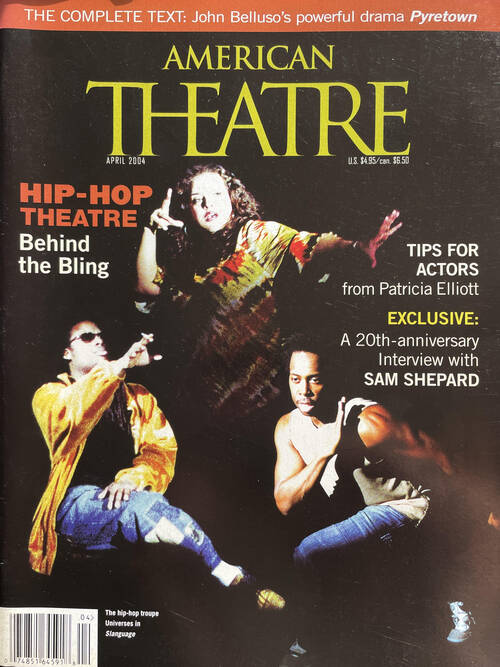

Other artists have benefited from, yet feel constrained by, the term. Mildred Ruiz, co-founder of Universes, bridles: “What we do is theatre. We come from hip-hop and poetry and our cultures, but what we do is theatre.” Still other artists who define themselves by hip-hop culture critique the cavalier use of the term. Choreographer Kwikstep champions what he calls “classic hip-hop theatre,” asserting, “People don’t know the history, so what you get is a bad carbon copy of a carbon copy.”

Still other artists, raised in the hip-hop era, acknowledge its influence, but they are concerned that hip-hop’s hegemony produces formulaic work rather than encouraging an expansive definition. The worry is that producers, presenters and those who are external to the hip-hop culture will recognize its presence only if marked by the most obvious characteristics of the four elements, thus narrowing innovations, subtleties and original points of departure.

Rather than grapple with these complexities, theatre—many artists feel—has tended to relegate hip-hop to audience-development/ “audience of tomorrow” slots, to second-stage outreach and education slots, or to token “minority”/”multicultural”/”diversity” /”artist of color”/”kill-two-birds-with-one-stone-if-it’s-a-woman-too” programming slots. The concern is that hip-hop theatre will become the latest and even more restrictive buzzword for the multicultural box, pitting artists against each other despite their differences in aesthetics and narratives. In the effort to build tomorrow’s arts audiences, conventional practice has been to approach the next generation of audience through education and outreach programs. At best, these invaluable programs inculcate an enduring appreciation of the arts—yet this approach can also be viewed as a type of missionary activity. Implicit is an assumption that young people must be brought to a higher culture, which necessitates the teaching of audience etiquette and proper behavior. It is assumed that our efforts to “bring them to art” are a positive alternative to what they would do left to their own devices, such as passively watch TV, hang out at the mall or join a gang.

About seven years ago, while running the New WORLD Theater of Amherst, Mass., I decided to leave the familiar comfort of a dark theatre to see where young adults, particularly those of color, are passionately committed as audiences and artists of their own volition. This led me to B’boy and DJ events, poetry slams, fraternity and basketball-step performances, and open mikes—in short, places where I was the oldest person in the room. But once I got over the age disparity, what I encountered was artistic virtuosity, experimentation and large, dedicated audiences defined as community.

Have you had a substantive conversation with someone under 20 (not your son or daughter or their friend) in the past month? I raise this question because linking with the next generation is not fostered in this society and often takes us outside of our comfort zone. Fear is an unstated barrier to engaging with teens and young adults, especially those of color. I’ve listened to countless conversations about “the next generation,” both in arts and social activist circles, without anyone under 20, or even 30, in the room. Very few think to include these young people in the conversation, or more important, go to where parallel conversations may be happening in their world. The next generation is valued, but not on their terms. In last year’s Broadway season, Def Poetry Jam and Full Circle’s Soular Power’d gave ample proof that a new audience and etiquette, one that is passionate and participatory, could exist in mainstream venues. Our theatres, however, appear at a loss as to how to consider, contextualize and support this work.

Even as it challenges definition within the theatre, hip-hop provides new examples of changing models of arts organizing, partnerships and networks. In numerous arts discussions, I’ve heard the question raised of the viability of arts organizations, as we know them. At an intergenerational meeting of producers a few months ago, Clyde Valentin, producer for the Hip-Hop Theater Festival, shocked all of us older folks in the room when he spoke up after listening to people waxing nostalgically about the National Endowment for the Arts. “NEA, NRA, it wasn’t there for us,” he quipped. “We did it anyway.” While the strengthening of the NEA continues to be a primary goal in the arts community, we forget there is a post-NEA generation; members also of the post-paradise AIDS generation, they are acclimated to living in perilous times and working outside conventional boundaries. They are media savvy and entrepreneurial, and while community is core to their work, their generational approach to network organizing often transcends their lack of resources and real estate.

Please understand: I am not a hip-hop head. Born in the mid-1950s, I am not of the hip-hop generation—even if I stretch the hip-hop timeline. My first intimate encounter with hip-hop was that of every other suburban soccer mom in America; it was through those little labels on those pre-DVD, pre-CD tapes that warned “Parental Advisory.”

It’s the late ’80s. I’m standing in an aisle of a music store at the local mall, realizing that everything on my son’s holiday shopping list bears that label. I’m trying to figure out if what I’m buying is the equivalent of buying him a carton of cigarettes and a six-pack of beer. It’s a horrible feeling.

Fast forward from a kid’s holiday shopping list to a 16-year-old’s extracurricular activities. My son and his best friend have taken the initiative to go to the University of Massachusetts radio station and request DJ licenses from the college’s community affairs department. They get their FCC training and become the first high school students to host a radio show. They call it “S and S’s 5 Boroughs,” which I think is funny, because my son was born and raised in bucolic New England. I don’t think he can name all five boroughs of New York City, much less find them on a subway map. But it’s all about the music, my son tells me. And the music is hip-hop.

One day he tells me he’s going to a station meeting because he wants to change the station’s policy. I say: Hold on a minute, you just got your show, don’t you think it’s a little early to start challenging the rules? He replies: The station won’t accept collect calls during his freestyle section. (Note: the freestyle section is a part of the show where instrumental music or beats are played and people phone in to rhyme or rap over them, improvising commentary—think of it as a creative talk show.) I tell him, I agree with the station policy, his friends shouldn’t be calling from pay phones, they should go home and call—collect calls are expensive. Then he explains that the collect calls are coming from strangers, inmates at a nearby prison within the broadcast area. His show creates a radio cipher that offers a means for young men—many of them just a few years older than my son—to have their voices and stories transcend their incarceration.

It is this changing terrain—the universal power that goes into and comes out of hip-hop; its ability to build across communities and make a huge impact, individually and collectively—gives artists and audiences the opportunity to pay attention to evolving aesthetics. Consider the speed of travel: My grandmother came to this country on a slow boat crossing from Japan. Compare that to the experience of a new South Asian immigrant—one moment in Delhi, the next in London, and now in Jackson Heights, Queens, where bhangra blends freely with hip-hop beats.

How is a high degree of media literacy shaping aesthetics? We tend to ignore popular media or view it negatively—after all, it is depressing as a theatre director to know that one episode of any mundane reality TV show is seen by more people than the combined audiences of a lifetime career. Yet I’m always shocked by the ability of young people to understand and interpret challenging non-linear theatre works—until I watch TV with them and see how they simultaneously watch several different channels and are able to tell you exactly what is going on. While this certainly is a comment on a lack of content, it also points to a type of technology-influenced, sampling consciousness that embraces juxtaposition and fragmentation. A permeable art form, hip-hop reflects and reinterprets the world around it; it incorporates legacies and the next thing on the horizon—and in a subversion of conventional appropriation, creates a space for democratic participation: Note the presence of Filipino DJs, German graffiti writers, South African rappers, and so forth.

It should be mentioned that in addition to the four disciplinary elements of hip-hop, the fifth element is considered to be knowledge. Hip-hop artists state that critics lack a genre exposure; their deficit of language—their lack of knowledge of history and terminology—further marginalizes innovative new work. They may like what they see without knowing breaking from B’boying; popping from locking; or toprocking from uprocking—the point is that even when hip-hop forms are noticed, they are not understood or critiqued from within the discipline vocabulary. This type of technical knowledge is as important as historical, cultural and self-knowledge. At the end of the day, it is this fifth element, glaringly absent from the marketplace, that may provide the space where art can flourish.

—Roberta Uno

Roberta Uno is the program officer for arts and culture at the Ford Foundation in New York City. A dramaturg, as well as founder and former artistic director of the New WORLD Theater in Amherst, Mass., she is the author of The Color of Theater: Race, Culture, and Contemporary Performance. This article, the first in a series on the convergence of theatre and hip-hop culture, was adapted from Uno’s speech at “Future Aesthetics: The Impact of Hip-Hop on Contemporary Arts and Culture,” a convening sponsored by La Pena Cultural Center of Berkeley, Calif., and the Ford Foundation.

Revising the Past, Pushing Into the Future

Hip-hop theatre, like hip-hop itself, is not easily defined. Born out of a creative urgency on urban streets, with self-produced rap tapes sold out of the trunks of cars and graffiti art works sprayed on brick city walls, hip-hop exudes a politics of survival and celebrates the “realness” of its underground roots, even as it is now globalized and commercialized and used to sell everything from sneakers to hamburgers.

Hip-hop, however, remains a counterhegemonic, postmodern cultural movement replete with contradictions and fragmentation that attacks conventional capital and consumption–even self-consciously flirts with the primacy of consumerist values. Hip-hop theatre interjects hip-hop ethics and aesthetics into theatrical form and content. According to playwright Robert Alexander, “For something to be truly a hip-hop theatre piece, it has to contain certain elements of schizophrenia and rebellion, creativity and destruction.” Hip-hop plays reflect a dichotomous spirit of social and cultural resistance and reaffirmation. They embrace the infectious, street-wise orthodoxy and survival instincts of hip-hop. They exult in the expression of the singular virtuosity, the bravado, the machismo and verbal dexterity of the solo rapper rocking the mike.

While hip-hop theatre is a new form of cultural expression, it still retains, repeats and revises the past as it pushes into the future. With its celebration of language, meter, poetic strictures, verbal play and display, it hearkens back to earlier traditions of oral expression in African-American culture, such as the spoken word of Gil Scott-Heron and the Last Poets, and even to classical theatrical conventions and the productive wordplay of William Shakespeare. Hip-hop theatre’s inclusion of actual, live rap music and DJ scratching and sampling, its allowance for freestyle improvisation, its embrace of non-linearity and presentational direct address to the audience, breaks with conventional theatrical realism and reflects contemporary artistic directions. And, at the same time, hip-hop plays agitate and engage critical cultural issues, connecting back to the oppositional aesthetics of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s and the theatre of LeRoi Jones. Like the earlier black revolutionary theatre, these plays prod and provoke. This is theatre that in its form and content recycles elements from the past, but with a new spirit of possibility and a new urgency that speaks to the racial and cultural hybridity of today.

—Harry J. Elam Jr.

Harry J. Elam Jr. is a professor of drama at Stanford University. This essay is excerpted from his introduction to The Fire This Time: African American Plays for the 21st Century, forthcoming this month from TCG Books.

Welcome to the Party

Before I created Rhyme Deferred, I did not consider myself a playwright. I was a theatre artist—a frustrated theatre artist and a “hip-hop head.” I was not seeing theatre that excited me and that reflected my generation, my culture. So this piece was created to fill my own personal artistic void. It initially began not as a story, but as an experiment to see the performance elements of hip-hop (DJ’ing, MC’ing, B’boying) on stage communicating with one another, telling a story. From this, Rhyme Deferred was born.

The piece has many biblical references, showing that every story has been told before, but this telling is employing a new aesthetic, the hip-hop theatre aesthetic: same story, different language, just “flipped into new meaning.”

This piece in particular is not meant to be read (neither is any theatre piece), and confining the piece to the page does it quite a disservice. The dance and the deejay are as integral as the words. Rhyme Deferred was written through artist collaboration and speaks to the ensemble performance feel as well. When the audience enters they should feel as though they are entering a hip-hop party, encouraged to dance, encouraged to talk back, shout back even. Though I didn’t realize it at first, it became clear that these were African performance conventions we were using throughout Rhyme Deferred (throughout hip-hop, for that matter), to show there is no separation between artist and audience.

—Kamilah Forbes

Actress, director and playwright Kamilah Forbes is artistic director of the NYC Hip-Hop Theater Festival and the founding artistic director of Hip Hop Theatre Junction, which will premiere Deep Azure in fall of 2005.

The Poetry of Slang

Universes creates work that is suitable for anyone who lives life. We did not set out to create theatre for segregated audiences. We set out to create theatre for the older houses and their subscriber bases as well as for the new faces that are promisingly beginning to flood into theatre seats. We do not “age out” audiences, because we communicate best through a combination of inherited and reinvented voices. We create work with an audience-development sensibility, where drastically different persons can sit side by side and share similar experiences, receiving a coded piece of themselves in the process. By offering delicately selected diversified samples of language, we invite audiences of all generations and cultural backgrounds to join us, while remaining true to our Afro-Latin-hip-hoppin’ voices. Through slang, we search and comb the gamut of language and culture, which make us who we are first and foremost: poets, a necessary label by trade.

Universes was not put together by a “making of the band” type of exploration, nor was it designed to fit a United Colors of Benetton ad. Universes created itself from the natural relationship born of friends and artists living in the same situations, working in the same circles, hitting on the same open-mike venues, writing with the same sensibilities. It was only natural for the five core members of Universes to come together as a community, one at a time.

We all met in the New York poetry scene—hitting at open mikes around the city was the name of our game. Varying in age range, ethnic backgrounds and experiences, each member of the troupe brings a different element of style to create five collaborating Universes in one very real world. Steven is the voice of jazz and literary style from the ’70s to now; Mildred the voice of cultural hybridity, mixing Spanish boleros with gospel, the blues and contemporary sounds and images; Gamal is “the bottom,” his roots reaching down into lyricism and music; Flaco, an old soul embedded in the young voice of salsa and NuYorican poetry; and Lemon, the voice that grinds through the streets of our reality, our urbanity. And, in this way, we found that “this ensemble would echo the exodus from exaggerated Ebonics to an eclectic experiment examining the everyday expression.”

In Slanguage, we promise to take you through what Lawrence Van Gelder of the New York Times described as:

... the underground rattlers, where the beggar, the battery seller

and the religious rile the riders; to the streets, where walking is

attitude; and to the tenements, where domestic disputes leave

babiesdead. But God is here, too, and Ali and Jack Kerouac and the

great Puerto Rican migration and Dr. Seuss; so along with the

politics of dislocation and the problems of assimilation and

richer and poorer neighborhoods and classrooms come fun and a

feverish joy of language.

That joy, Van Gelder aptly noted, is “expressed in rap and riffs and gospel and bluesy laments, among other poetic forms.”

Welcome to our Universe and the language from which we are born. Where we reclaim our inherited voices and remix them with our own.

—Gamal A. Chasten, Lemon, Flaco Navaja, Mildred Ruiz and Steven Sapp

Universes will appear at the Mark Taper Forum in May.