Some comforting news for worried designers toiling in the fields of the not-for-profit theatre: It is not your fault. You are not supposed to be able to make a living working in the not-for-profit theatre.

At least, that is the consensus of a group of 26 busy set designers surveyed over the past few months for an update of an article, published in American Theatre more than a dozen years ago, about the cost of doing business as a set designer.

That short essay, “Designing Money” (June ’89), lamented the inability of even the U.S. theatre’s best-known, most in-demand freelance designers to earn an adequate income from the practice of their craft. “Designers are notorious suckers,” the article stated. “We love to design. We will even accept substandard pay for the privilege.”

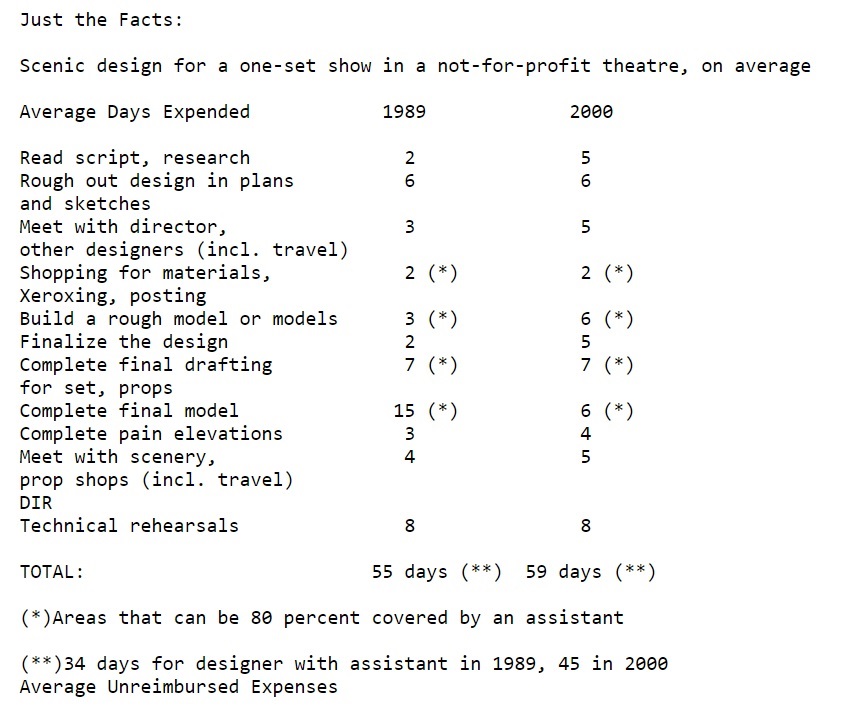

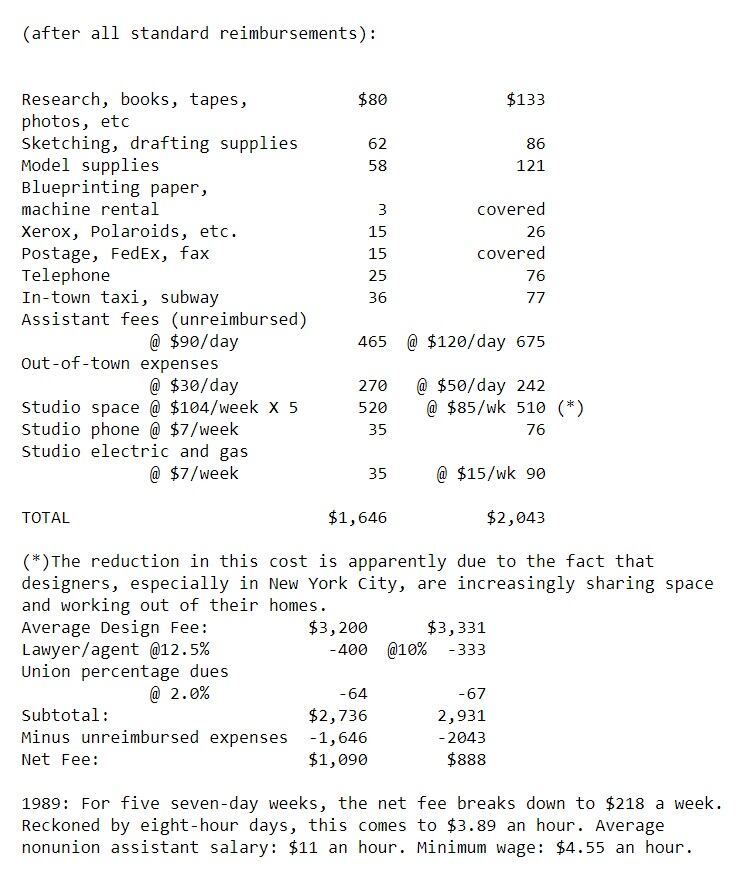

Documenting the design field’s “willingness to be exploited” was a detailed chart of time expended, unreimbursed expenses commonly laid out by designers and standard fees for “a one-set period show in a mid-sized regional theatre.” The conclusions were dismal: A designer working in such a situation earned, on average, $3.89 per hour. At the time, the minimum wage was $4.55.

(Incidentally, according to American Theatre‘s editors, over the life of the magazine, “Designing Money” is second only to August Wilson’s “Ground on Which I Stand” speech in the number of copies and reprints requested. In this update, the quotations from designers punctuating this article will remain, as they did then, unattributed, for obvious reasons.)

“I believe we can’t come close to surviving on our design incomes.”

What has changed since 1989? Expenses, naturally, have gone up significantly. Design fees have not. The highest reported fee for a one-set show in the 2000-01 season was a single LORT A fee of $8,600. The lowest were several of $500. The average fee, based on figures from 46 shows mounted in theatres of various sizes, was $3,331, an increase of $131 since 1989.

During the original survey, designers complained that the huge number of shows they had to take on in order to pay their rent was seriously compromising the quality of their work. By 2000, most of the respondents have given up even hoping to make a living from designing shows. Now they simply accept that if they wish to go on doing what they love, they’ll have to look elsewhere for a livable income.

Today 75 percent of working scenic designers are also teaching. Those not teaching supplement their income as stage designers with non-theatrical commercial work—or are young enough to be willing to design 10 to 12 shows a year and still barely break even.

“I work as an art director now, and although I am often creatively bored, I no longer go to bed with the worry that I’m going to end up as an old [person] with a tin cup in my hand and a bunch of Playbills and glowing reviews in my pocket.”

A tone of resignation and betrayal haunts the commentaries that came along with the grim facts and figures of the survey. The designers point our that they have been hustling along with everyone else, supporting not-for-profit theatres with their time and labor until the day when the producing organizations might become stabilized and self-sustaining. That day, most people agree, arrived quite a while ago, but designers feel they are still expected to work essentially for free.

Another point of agreement was that in the institutional theatres of today, the faces seen daily around the coffee urn—the development assistants, the subscription or educational outreach staff, for example—are more highly valued than the artists, most often freelancers, who create the product those staff members are selling. Many respondents asked: Does the institution exist for its own sake or to make a home for the creation of theatrical events?

“I have mentioned recently to producers that I sometimes make about what their interns are making, if I add up time versus expenses.”

For their part, the institutions are fond of implying that fees and payments should not determine an artist’s commitment to “the work.” They explain that they also are hard-pressed by economic issues. But how then, designers ask, have permanent staff salaries and benefits at these institutions become so competitive? If these are theatre-producing organizations, aren’t their priorities a bit skewed? Who will be left to create the actual theatre, if all the artists have been sent off empty-handed to the universities, to Madison Avenue, to Los Angeles?

“One artistic director told me this was okay, as I received ‘psychic remuneration.’ I replied that my landlord did not accept psychic remuneration.”

Though the survey asked designers to focus their replies (for clarity’s sake) on single-set shows, several took the opportunity to protest the standard one-size-fits-all payment structure, where the fees are unrelated to the scenic requirements of the show or to the actual time needed to design it. The management, they noted, can believe to their hearts’ content that a particular three-act play would look best on a unit set, but paying the designer that way does not guarantee that the director will agree to the concept.

Other designers feel that the institutional managers are suspicious of designers’ fiscal responsibility. Because so few managers have ever lived through the full design process, they simply do not believe that it could cost as much as it does. Look, they say, we reimburse all reasonable expenses; the designers are profligate; the designers are flaky; the designers can’t properly manage their own business. But, the designers counter, lean and clever management is exactly what’s required to keep a career alive on such low profits.

The theatres have made a gesture, it is true, in the direction of expense reimbursement. In 1989, the only widely reported categories of reimbursed expenses were housing and transportation. Since then, several sorts of expenses have been added to the list, from blueprinting and model-making materials to FedEx charges. It is interesting to note that more experienced designers report considerably higher percentages of expense reimbursement, particularly from theatres where they work regularly. These theatres seem willing to pay for items that actually show up in the building, plus the price of getting them there. But thanks to recent fractious negotiations over a contract with United Scenic Artists, a miniscule cap was set on those expenses without ever polling the designers as to the actual costs.

“A fully painted scaled model is now expected by producers. This is a lovely way to work—I think it’s the best way—but it’s extremely labor intensive and time consuming”.

Expenses that don’t directly produce a visible product, such as research materials, studio overhead or the extra cost to the designer of living out of town while in residence at a theatre—these are costs the designer is regularly expected to absorb, with little consideration given to whether the fees paid are anywhere near adequate to cover these expenses.

And today there are a host of new expenses. Since 1989, the computer revolution has changed the way we all do business. Today a designer must own a scanner and be at least conversant with PhotoShop, or be considered obsolete. These renovations do not come cheaply, particularly where graphics-friendly hard- and software are concerned. Institutions can bear the cost of a $2,500 computer or a $600 program more easily than the individual artist, but once the theatres’ shops are running CAD and e-mailing molding details back and forth, the designers must keep up. Here again, many designers have found relief from their teaching or corporate day jobs, where the equipment they use belongs to the institution they work for.

A similar strategy is common for dealing with health insurance, another rapidly spiraling expense. Several designers report being unable, given their low design fees, to produce enough income to be eligible for their own union’s welfare program. A clear majority of the respondents rely on the health coverage supplied through their universities or their spouses’ jobs. Many others simply have to pay for it themselves, to an average cost of $2,033 a year, two-thirds the amount of an average fee.

“I try, without being too negative, to alert my young eager students to the reality of life in the theatre. And like all young eager students, they really don’t believe me.”

And then there is the issue of design assistants. In 1989, most of the designers surveyed reported employing assistants in their studios to help with shopping, model-building and sometimes drafting. In 2000, less than half report using assistants. Most say they can’t afford it. Yet the figures show that if they did use assistants—judiciously—they might well make more money, at least on an hourly basis. Theatres will usually pick up a portion of assistant fees, and having help in the studio cuts down the time required to produce a design by about 25 percent.

The saddest irony is that assistant designers make better money than the designers themselves, with many fewer expenses to cover. The average assistant rate was reported to be $120 per day, a considerable cut above the average designer’s net daily rate of $21.14. (See chart below.)

Assisting has been a traditional way to pay the rent in the early years of a career and, meanwhile, learn the practical aspects of the trade. However, there are more and more young designers being graduated from theatre training programs (the same programs that keep the more experienced designers alive) and less and less assistant work available to them. None of the survey respondents reported being able to employ an assistant year round, as was common 12 years ago.

The Social Darwinists of the world will shrug and point out that no one forced us to engage in what has become an apparently non-viable profession. There is a certain ring of truth to that notion, and designers by and large are pragmatic folks. Their sense of having been betrayed is leavened by humor. After all, what sort of rational discourse is to be had with an employer who, on the one hand, goes on and on about how vital you are to the process, and, on the other hand, refuses to offer you a living wage?

So designers continue to make do, one way or another.

“Could it be that designers are more involved in the developing and changing dramaturgy of the whole production…an acknowledgement on the part of directors (and often with the reluctant consent of the playwright, if it’s a new work) that the design is a more crucial part of a production than a mere narrative illustration or mood inducer?”

A final notable result to emerge from the survey is that the length of time to complete the design process on a typical show appears to have lengthened, from 55 days to 59. This is despite less overall time spent in residence at the theatres, and despite several designers’ claims that they consciously “cheat” on the time spent on reading and research in order to save a few pennies. Again, it is the longer-career designers who report shorter process duration—though even the fastest of us could get the time span down to was 31 days, with liberal applications of help from assistants.

Why has the designer’s working time increased, when advances in materials and technology suggest it might be otherwise? I’ll conclude with one senior designer’s interesting explanation:

“My sense is that more young directors are demanding more from designers. That’s good, but it has increased the time commitment and the design’s importance. So… where’s the recognition?”

Marjorie Bradley Kellogg’s designs will be seen in An Infinite Ache at New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre and A Tender Land at Milwaukee’s Skylight Opera Theatre in December and January.