This is the final part of a three-part series on the 15-member class of 1995 of American Repertory Theatre's Institute for Advanced Theatre Training at Harvard University. The first part—an extended dramatic personae: 15 actors, 15 lives, 15 stories—can be found here. The second—following the cast of characters as they begin their professional careers—can be found here. In this concluding segment, the young actors offer a candid assessment of the spiritual awards and material costs of their first year as actors in America. —The Editors

Now I finally see it, Kostya, that whatever we do—acting or writing or whatever—the main thing isn’t about fame or glory, not all that stuff I dreamed about, it’s being able to endure. You’ve got to bear your cross and have faith. I have faith, so it doesn’t hurt so much. When I think about my calling, I’m not afraid of life. —Anton Chekhov, “The Seagull”

SPRING/SUMMER 1996: Chandler Vinton has just finished reading Milton’s Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. She has a lot of time on her hands. Although she worries that she’s not hungry enough to succeed, that she’s “hiding out from the fact that this is a business,” she also has a voice inside that says, “Make sure you’re happy.” For now, she’s happiest in her new apartment. “My definition of making it is not, ‘I’m going to L.A. to be a big star,'” she explains. “I keep trying to tell myself that that’s okay, that mine’s not less or worse than someone else’s ambition. But I’d rather sit home and read about God.”

Making a home for herself has been Chandler’s response to the feeling that hit her within months of her move to New York: “It’s like I’m waiting here at the world’s disposal.” Chandler knows that it may take years before she grows into the parts she suits; she hasn’t known what to do while waiting. The answers come to her gradually, over the course of the year. Her first apartment, a minuscule Upper West Side studio that rents for $1,050 a month, barely has room for her and her two cats, so she locates a floor of an actual home in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, a family neighborhood, and moves there. She retrieves from storage the furniture she got when her mother died, and cozies up the place. She reads. Early in the year, she takes two jobs—she’s never had to work before—and derives from her own competence a dose of confidence. First she replaces an executive secretary on sick leave from a major advertising agency, a job that brings in $16 an hour and sets her crowing on the phone, “I’m making money!” Then she books a couple nights a week as a cocktail waitress at a place called Jake’s Dilemma. She is maid of honor for her mother’s sister’s wedding and, as a gift, her aunt pays for her to start psychotherapy, another important beginning. For a time she works out.

In a year that offers little hope of high achievement or major reward, these small steps are saving graces. “I’m feeling very good about reading, good about working out. I feel proud of the fact that I’m a good cocktail waitress.” While nothing completes itself for her this year, she becomes aware that “all my processes are probably 10-year processes, not yearly ones. What’s most important to me now is meeting people who share my interests and aesthetics.”

Not everyone can afford the luxury of patience. Chandler, though, belongs to that illustrious heritage of haute bourgeois theatre people with the means to bankroll their own dreams. She can pay for an audition class; join an organization that helps actors write résumés, organize mailings and network; and explore alternative careers in the arts by interning, unpaid, at New York theatres. She can punctuate the unspectacular year with revitalizing family trips to Grenada or Georgia’s Sea Island or visits to her father’s home in England. Thanks to her banker dad and a small inheritance from a distant relative, she can buy more time. This privilege is a blessing, one that Chandler is only beginning to register. “I’ve had a pretty easy life. Shitty things have happened, but it’s been easy.”

Is anyone’s life really easy? Chandler lived with her mother’s paranoid schizophrenia and survived, at 16 years of age, her suicide. Her classmates, some wealthy, some not, have suffered other traumas and tragedies. Is it the ease that makes an artist or the difficulty? Is acting a way for a woman of privilege to forge a personality outside the comfort of home, or is it an opportunity for healing the wounds those same comforts mask? With Chandler it’s hard to tell: She’s so solid, and so adrift. As she talks, she wanders throughout her apartment. Sometimes she picks something up, a knapsack or book, as if on purpose, only to set it down randomly, wherever she winds up.

This middle territory, this in-progress state, is hard to describe. When, by way of contrast, Ajay Naidu snares the part of Nazeer, the Indian convenience store owner, in Richard Linklater’s film of Eric Bogosian’s SubUrbia, he has names to relate and details—of rehearsing in L.A.’s Chateau Marmont, for example, a swanky old hotel where John Belushi died. This big break is followed by another—an episode of HBO’s Subway Stories, produced by Jonathan Demme and Rosie Perez and costarring (with Ajay) Danny Hoch and Sarita Choudhury. A single dramatic event, that of landing a movie, gives way to a story of momentum, a young career on a roll. Days later, that story gains power when an Italian director hires Ajay for the leading role in a third movie, Once We Were Strangers, about a young Indian man who, having immigrated to America at the age of eight, faces an arranged marriage with a woman from his homeland.

But consider Chandler’s story. Without defining events, like Ajay’s string of jobs, a year that may turn out to be pivotal can look positively uneventful. The defining peculiarity of the actor’s life arises from this disjunction: between the randomly reinforced rhythms of theatre employment—auditions, no auditions, callbacks, offers, contracts, dry spells, got-its and lost-its—and the slower, steadier pulse of ordinary days.

After a pleasant, horizon-expanding few months at the Actors Theatre of Louisville, James Farmer returns to half-a-year of daily life. He makes ends barely meet by waiting tables at the rooftop restaurant in Bryant Park and tending bar in Brooklyn Heights at the Montague Street Saloon. He does some showcase acting and a couple of readings with friends. He obsesses over little details from auditions or things his agent says to him on the phone. He starts to feel “kinda crazy,” just hanging on to himself. Then, for the first time in several years, Tracy—his wife of nearly a year, finished with her own graduate program—comes to town to stay. Now they have to learn to be together.

All this takes time, and it unravels in a distinctly undramatic fashion. “I’m trying to be happy with what I have,” James explains. “Things are going okay, however slowly.” He’s starting to feel comfortable in New York and to accept more constant rejection—especially now that he’s being sent on more auditions—than he’s ever faced. He makes a Red Lobster commercial on Long Island and Fire Island—you know the kind, handsome folks walking around on docks carrying bushels of lobster on ice, “people having far too much fun.” When it goes national, he finally has some money in the bank, but nothing compared to the $100,000 he and Tracey owe on their school loans.

With the exception of his pared-down Shakespeare performances in city schools and at the Museum of Natural History, Tom Hughes accomplishes a lot more this year as a writer of books for young people and as a future father than as an actor. He goes on a sprinkling of auditions, many for Shakespeare plays, mostly for Horatio-types—supporting players with integrity. “I’m not the kind of guy who gets cast as Macbeth or Hamlet. I’m too even-keeled.” And he’s in it for the long haul, despite a lifestyle that contradicts almost every actor stereotype—homebody, husband, and devoted churchgoer. (His wife, Kristen, has already shelved the idea of acting and found a less flashy career, one she loves, as a teaching assistant at an Episcopal preschool.)

When his agent signs him for two more years he’s told, “If you can be patient with us, we can be patient with you.” He considers each part of himself in light of the whole: personally happy and professionally dissatisfied, ready to do more to take charge of his work, to be the “agent” of his own career. Worries about money—income, debt, and insurance—wear him out.

Every concern is swept aside, though, by one. And before long he’ll modem a message to my e-mail box. “Two days early, and not a moment too soon, Steven Thomas Hughes, with some assistance from his mother, a vacuum, a pair of forceps, and a platoon of medical personnel, emerged from a murky world of moist darkness into one of bright lights, cold air, and non-self-cleaning diapers…Date/Time of Birth: Friday, Nov. 8, 1996; 7:26 a.m.”

If the Institute of Advanced Theatre Training at Harvard’s class of 1995 had taken a poll, Kevin Waldron just might have been voted most likely to enter the clergy. Now, with neither pomp nor circumstance, he’s done it. His was a mail-order ordination, sent away for and bought with the sole purpose of performing Todd Peters‘s wedding ceremony. Kevin’s holy orders came in an envelope from the Universal Life Church in California, which has been anointing people by mail, the story goes, since the Vietnam era. At the time these postal priesthoods were especially popular among draft-eligible Hollywood actors looking to authenticate their conscientious objections to the war. If this subterfuge was a tactical hypocrisy, it was also an actorly one, since priests and actors are related at their roots. Performance springs from worship, and the rituals of worship emulate theatre. Like the clergy, many actors express a fundamental spiritualism that jars with our secular age. Kevin’s blessings will be on display on Saturday, the 26th of October, 1996 at 4:00 in the afternoon in San Diego, Calif., reception to follow.

How Todd has come to win the part of Margo Porras’s bridegroom is another story. On Oregon’s Cannon Beach a couple weeks after graduation last summer, he scrawled a proposal in the sand. (Years before Margo’s father had written a similar proposal with a stick in the dirt.) In “one fluid moment,” he slipped an engagement ring on her finger and they began strolling, as the sun set, amid the massive coastal rocks. Little did Todd know when he found the courage and grace to pledge his sandy troth that this moment of flow would be about the only time all year that he’d feel in command. He’s thrilled about the wedding, but he complains all the time because, as with everything else in his life, it feels like it’s out of his hands. His notion of waiting two years to get married gets whittled down to “next October.” His family-by-marriage-to-be arranges the purchase of a New Jersey co-op for the couple. Meanwhile, Todd looks on, suddenly aware that trying to stop this juggernaut of energy and will “is like trying to hold the ocean back with a broom.” Todd might grumble, but he does so winningly, ironically acknowledging his commitment and readiness to play the part of married man. The passing year shows him, though, that he is nowhere near as ready to assume the role of New York actor.

By dint of some unique charm, Todd is able to depict himself as the active agent of his own inactivity, a character whose lack of chutzpah approaches the heroic. Moreover, he transforms even the most uneventful detail of his actor’s existence into a dramatic event.

He has quit his mole-like existence as a graveyard shift computer operator and is in high spirits, as if the year has agreed with him. He seems taller, brighter, more redheaded than ever. Todd usually has a story to tell—often an upbeat tale of personal failure. He recounts the life-changing experience of playing the title character in Ödön von Horvàth’s Don Juan Comes Back from the War in a master’s thesis production at Columbia University. Everything was going miserably and then his worst nightmare came true. His best friend Randall Jaynes came to a preview and told him the show was so bad there was nothing he could do to screw it up more.

Something opened up in him. He began to have fun, to concentrate on just telling the story. The performance grew 100 percent on opening night, he claims, and 100 percent each night after that. The experience changed him. “Suddenly I just realized, I can do this. That made me feel like an actor.” Now that he’s tapped this confidence in his acting, he’s energized to “start acting like an actor.”

“I want that life more than anything. It’s been so long waiting, so long being afraid. Not doing it has become more painful than doing it. I want to look like an actor. I want to have a bag like an actor. I want people to think about me what they think about [classmate] Sherri Lee. I want them to say, ‘He’s an animal.'” I assume this new energy has accelerated his attempt to pile up 100 rejections before year’s end. (When I inquired a few months earlier, he’d only gotten the thumbs-down half-a-dozen times.) So I ask for a tally.

He stops a minute and mumbles something about, “Should I or shouldn’t I tell you?” Then he confesses. “The closest thing I got to doing an audition was being a reader.” He admits to lying last time we spoke. He hasn’t had a single audition since hitting New York 13 months ago (Don Juan was simply offered to him). Now, though, he’s raring to go, and he’s got this incredible network of school friends—his “mafia”—to back him up. Sherri has even offered to escort him to auditions. He tells Kevin he’s “ready to be an actor” and Kevin says, “Well, it’s about time.”

Sherri Parker Lee, it appears, was born ready to be an actor, but only now is her readiness paying off. After a full year of rapid-fire auditioning, constant callbacks, and numerous near-misses, she lands a paying soap opera job and then a play and finally, following months of herky-jerky negotiation, a six-month repertory contract. “I’ve always been a person who says ‘I want that; I’m going to get that,’ and I’ve gotten that. Somewhere subconsciously I project myself into the future.” When the future first rises up to greet her, however, it’s not a pretty sight.

Sherri screentests for a character on As The World Turns and is given every indication of having it in the bag. Ultimately, though, her agent tells her, “they went for type over talent,” deciding they didn’t want a blonde. A week later the show calls to offer a small part they’ve created with Sherri in mind, a spoiled rich-girl biker, who drives into town with a new male lead, a Calvin Klein model who’s never acted before but has secured a three-year contract. Sherri’s treated very well, and members of the cast compliment her on her earlier test. Her first scene on camera, which, due to the new guy’s inexperience takes seven takes, consists almost entirely of kissing, with him cramming his tongue in her mouth. (After each kiss a female union representative comes over and asks if she is okay.) She’s given notes like “flip your hair” and “pull your bikini down.” Sherri cries when she sees the debacle on TV, but her grandmother, a big fan of the show, calls its 800 number 25 times to say how much she likes Sherri.

Things get better. After a previous New York audition for the Alley Theatre of Houston’s production of Nicky Silver’s The Food Chain, she’d written a thank-you note to Gregory Boyd, the company’s artistic director. When she’s called in for Brecht’s In the Jungle of Cities, he thanks her for the letter. She goes for broke with her singing audition, preferring “strong but wrong” to unnoticeable. Afterward, he requests that she stick around. When he finishes auditions, he invites her to walk with him. As they move along 43rd Street, he asks her if she’s interested in joining the company on a season contract. A firm offer is made over the phone later only for a part in Jungle. Sherri accepts, goes to the Alley until October, returns, negotiates some more, and finally, this past January, flies down for a six-month stay, which includes playing Electra in a three-part cycle of Greek tragedies. The groundwork she’s laid fastidiously each and every day of this year is paying off. Her boyfriend, Dan, has only days ago moved to New York with his 12-year-old son, despite some initial ambivalence on Sherri’s part. Once he arrives, she’s happy to be reunited and committed to being committed. Her anxiety over the right course of their relationship departs, but then so does she.

There’s a classroom exercise in which actors bring onstage with them something from their lives—something that jumpstarts their belief in the given circumstances of a scene. The performer works with this object—a photograph, maybe, or article of clothing or childhood toy—as a way of navigating between now and another time, one ripe with associations and feelings. This object becomes a real key to an imaginary world. The exercise is also emblematic of the actor’s ongoing struggle: Faced with empty space, spirit-numbing obstacles, and a life of creative expression that exists only in the imagination, actors must surround themselves with people and things that create—within them—faith.

“One of the most important things is surrounding yourself with really supportive, positive people,” insists Suzanne Pirret. Building a community of loving others becomes the bulwark of her faith in herself. Everyone who doesn’t fit that description, she literally whites out of her address book. She chooses her influences carefully, accentuating the positive. She looks for a teacher and an agent who believe in her, and ultimately finds both. Her new acting teacher, Wynn Handman, creates for her an intense and supportive, free-to-fail environment. He helps her find herself by finding comedy and by encouraging her to stick to character roles. Similarly, she signs with a new commercial agent who is consistent and excited about her. They speak on the phone several times a week and are, in Suzanne’s words, “like family.” Her blood family is, likewise, there for her, with love, support, and, until she locates a place in the city, a home. She’s also part of an ongoing comedy group, all alliances that help dispel the “black cloud” that threatens when acting work isn’t there. History is repeating itself for Suzanne this year. Having returned to New York, she’s taking classes again, pounding pavements again, and, in her second autumn back, bartending in a new version of the same restaurant she worked in a few years ago. This sense of recurrence conceals an energizing difference: This time around she’s not alone.

The reverend Kevin Waldron may be no evangelical, but he is a good listener and a deeply spiritual soul. So when the New York he’s fantasized about taking by storm takes him, instead, for a loop, he turns to meditation—”a lot of meditation”—as a pacifier. He reads Deepak Chopra’s The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success four times, drawing connections between laws of the spirit and the practice of acting. In daily life, for example, you can never know ahead of time what will happen. The same is true onstage: Actors must avoid thinking ahead or trying to recreate successful scenes by doing exactly what they’ve done in the past. As a person and an actor, Kevin has come to believe, “You need to embrace uncertainty.”

Spiritual laws come into his relations with others, too. Kevin shares an apartment with close friend and fellow alum Randall Jaynes. It’s a funky little East Village cove, owned by Randall’s employer, Blue Man Group, and renovated by Kevin and Randall (with Blue Man money) from a state of stripped, utility-less, maggot-infested wreckage. As part of their continuous bolstering of each other, they entertain the “law of giving.” They describe their ideal apartments, and Randall suggests, “When one of us really makes it, let him give the other the ideal apartment.” The class of 1995 may not have stayed together as a company, but in their various moves to New York, they stay together as a support network, sometimes one on one, sometimes in cells, groups splintered from the whole. Their telephones ring back and forth. They crash on each others’ couches, collaborate on projects, and offer advice as well as figurative kicks in the pants.

By quirk of fate, Ajay Naidu lives in the adjoining building on the other side of Kevin and Randall’s nonworking fireplace. There he makes his way through a workbook of his own, melding art, psychological healing, and spiritual aspiration: Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way. He calls it “creative I.V.” Like Kevin, Ajay has shifted from early religious teachings to a more individualized system of belief. He emphasizes that his career choices have always been his own, that instead of being pushed, in a way typical to Indian families, he’s created his own path. This includes the spiritual. Once a “heavy Hindu kid,” he’s a “heavy Buddhist now.”

Both Kevin and Ajay’s guidebooks offer practical steps to spiritual ends, a worldly and otherworldly mix that seems at home in the motley East Village. A quarter-century ago, theatre critic Kenneth Tynan dubbed Greenwich Village “the internment camp of Manhattan nonconformity,” a label now more suited to the low-rent chic of St. Mark’s Place, where, within shouting distance of a new upscale Kmart, junkies hang out in front of Japanese-inflected health food restaurants and a fetishist boutique called “Religious Sex” sells leather and lace up the street from the Gap. The bohemia of the early ’80s is this decade’s designer mall. Smack in the middle of the block—visible from the actors’ windows—a community center for recovering addicts shelters a regular round of 12-step meetings, offering the support of human fellowship and a self-defined “higher power.”

When Siobhan Brown tackles the first six weeks of The Artist’s Way, she’s “reminded of everything I’d been taught in Christian Science that I liked and wanted to take away with me.” While she started the year feeling the strain she’s put on her intimacy with her mother by not following her mother’s religion, by year’s end, intimacy and distance have settled into an easier balance. Her spiritual direction seems more a modification of than a break with her Christian Scientist upbringing, which she learns is “nothing I can ever leave behind.” Prayer and spiritual definition become daily, self-sustaining practices in a difficult year.

The pursuit of spiritual ends has an intellectual cast for Mark Boyett, though his personal history suggests much more. Mark’s strict religious rearing included four years boarding at Ben Lippen—Mountain of Trust—a fundamentalist Christian high school in Asheville, N.C. If it hadn’t been for a friend who was applying to ART and who encouraged him to do the same, he might have begun graduate study in religion. His “drift from a faith of sorts” occurred gradually, assisted in small measure by a dawning homosexuality that started him entertaining “the notion that the Bible as it was taught to me is not true.” Now Mark’s bookshelves show a continued interest in matters of devotion. The theological abuts the thespian, as Shakespeare and Stanislavsky lean against contemporary religious studies, such as The Gnostic Gospels and The History of God. I wonder what his 12th-grade tutors would have thought of his profession and of the infidel acts he’s hired to perform this season: cavorting as the devil in Beethoven and Pierrot at Denver Center Theatre; defending the Talmud as a Hassidic yeshiva boy in The Dybbuk; impersonating, in Brecht’s Galileo, a failing Old Cardinal who insists the world is flat and still; and, for Old Wicked Songs Off Broadway, understudying the role of a 25-year-old piano prodigy, who keeps his Judaism in the closet.

Vontress Mitchell, reared a Baptist, “was in the ministry at 15.” In college he detoured to Boston for conservatory training as a singer. His mother and five surviving brothers have all experienced comforting visitations from his younger brother Corky, since he was shot and killed by the Wichita police two years ago. Vontress has not. “Corky knew I’m the most fearful person when it comes to this spiritual stuff,” he explains, as though his brother’s spirit has purposely avoided him. They used to joke about it, and Vontress told Corky that if anything ever happened he should stay away. “I said, ‘Don’t visit me; I will rebuke you.'” At one point, during his return home in early spring, he finds the house his brother lived in so eerie that he asks his mother to keep the bathroom light on.

When New York weighs on Vontress—when it appears that “everybody needs something; everybody has an agenda, and if you’re not there for them, you’re in the way. I have a deeper need for why I’m in it. I’m unhappy here because I’m constantly having to protect that need.” Sometimes the effort isn’t worth it. In August, Vontress leaves New York for San Francisco to play one of the five sages of Chelm in Shlemiel the First; he originated the role at ART, where the musical, based on stories by Isaac Bashevis Singer, was developed.

He’ll join most of the original cast at the American Conservatory Theater—still the only African-American Jewish wise man onstage. (This is after playing Roderigo in an all-black cast of Othello with a company of ex-Juilliard students in Manhattan.) He’s not sure, though, whether he’ll come back to New York or even continue acting. While rooming with family in Oakland, he stays in a lot, watching TV and listening to music. He reads The Care of the Soul by Thomas Moore. (If the self-appointed moralists of American life assault the theatre as a godless place, let these young artists stand as proof that it is anything but.)

For Tom Hughes, the deeper needs have outlets other than theatre, and spirituality goes hand in hand with doctrine. An active Mormon, he is part of a lay priesthood that firmly believes in modern revelation and a ongoing heritage of prophets. His family in Utah also belongs to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. His father, head of his congregation in Provo, holds the five-to-seven-year unpaid post of bishop and the designation of high priest. Nevertheless, Tom describes Mormonism as something you choose, the result of personal, spiritual conversion. “All worthy male members of the church from 12 on up are priesthood holders, so it’s just part of your life.” Now he is an Elder Quorum President for his congregation, a largely administrative post that involves overseeing “home teaching” visits to each family in the congregation to make sure they’re okay. He’s gratified to be on call like this and to be of service.

Unlike his classmates, however, he doesn’t see theatre as particularly continuous with religion. “I wouldn’t say I put any religious value in it. I find my meaning for life in my religion and my life. I see theatre as a place that shows us life, explains it.” He tries to articulate the conscience his beliefs set up in him—the constant search for worthiness—by quoting the Mormon character Joe Pitt from Tony Kushner’s Angels in America: “The failure to measure up hits people very hard. From such a strong desire to be good they feel very far from goodness when they fail.” God is not a way out of the consequences of personal action or, as the case might be, inaction. Rather, the will to be good, and the attendant self-judgment, underscores a principle of faith Tom takes to heart: personal responsibility, or what he calls “agency.”

Agency. It’s an unavoidable pun. Actors hope for agents who will share responsibility—agency—for their careers. They look for the right match of support and savvy. They find all sorts of things. Some agents strive to keep their clients in town, some send them out only for regional work. James’s agent loans him the money for new head shots, and others do no more than warn, “You need new pictures,” and then don’t submit them for auditions until the expensive eight-by-tens have been delivered. Randall’s representatives, who receive no percentage for Randall’s Blue Man Group performances and his solo appearances at international festivals, get a big bonus from him at Christmas. Some offer the clout of well-known agencies and some the intimacies of a small, new staff. Still others seem to forget their clients exist.

In the end, though, the power is mostly on the other side of the casting table. Jessalyn Gilsig‘s agents may be able to line up major league auditions, but they can’t guarantee her roles. When she lands the part of Sunny in the world premiere production of Driving Miss Daisy author Alfred Uhry’s new play, The Last Night of Ballyhoo, scheduled to open at the Olympics in Atlanta, they can negotiate her contract, but they can’t ensure she’ll reprise the role on Broadway. In fact, after working with Jessalyn in Atlanta for four months (including a two-month sold-out run at the Alliance Theatre), Uhry and his producers and director keep her on a string for several months before deciding on someone else for the Broadway cast.

Some things no one controls. Jessalyn is in Atlanta watching television when the bomb goes off. Later, the theatre has bomb scares of its own. One night the actors get word that there’s an abandoned package upstairs but that they are expected to keep performing until the house lights go on—then they should head for the exit. Before another show the cast wanders into the green room to find five volunteer security people staring at a bag in the corner, as though they don’t want to see it because it means they have to deal with it. Nor can Jessalyn, a Canadian citizen, control whether or not she’ll have her visa renewed, though her agent and new lawyer are helping gather letters that make the case that she’s an asset to the U.S. She rules out marriage; she and her boyfriend aren’t ready. From June until late October she waits to hear, “sort of freaking” the whole time. When she does hear, her visa is denied. She is supposed to leave the country immediately.

She then learns that this is a mistake. An essential letter, written and sent, has never found her file. Still, the glitch means more waiting and, finally, reentering the country with her new papers in order. She leaves for her sister’s in Montreal and bides time until her entry visa arrives.

For all his good fortune in this thrilling career year, Ajay can’t control his father’s decline. In early August, Dr. Naidu enters the hospital with a mild heart attack. With a history of coronary trouble and diabetes, surgeons won’t operate on him. Ajay speaks to him the day before he checks into the hospital. The next day, when he arrives in Chicago for a week-and-a-half vacation, his father is in a coma, apparently after suffering a stroke. The doctors shunt the blood from his cranium and for a while he’s responsive. Then he slips into another coma. He never regains consciousness.

The family decides to pull him off the respirator and only give him food, knowing that he wouldn’t want to live on life support. On Aug. 11, he dies in Ajay’s arms. “I was holding him and my mom was there, across from me.” Two of Ajay’s uncles and one of his aunts are also in the room as 65-year-old Dr. Naidu gradually stops breathing. Ajay speaks for the family at the funeral. His father is cremated; half his ashes get strewn in Lake Michigan, after it is consecrated by an Indian priest. The other half will be spread in the Ganges.

Ajay returns to New York, where over the next few weeks, he shoots three films. He is on his own in ways he can only begin to imagine.

Granville Hatcher also learns a bit about the illusion of control. He sees his character work edited out of his first Hollywood movie until, as a principal Lebanese terrorist, he’s “basically a face with a gun.” He stands by while his second movie, a fact-based black comedy about the World Trade Center bombing, in which he plays a Jordanian chemical engineer, is held from release until the Josef case concludes in New York City, so as not to taint a fair trial. He loses the chance to flesh out his third and smallest role, as an Americanized hispanic lawyer in a TV show starring Stockard Channing, since the pilot doesn’t get picked up by the networks. The possibility of this continuing role is reduced to a single day of work, one line in one scene, played naked from the waist up, in bed. “Our job,” he determines, “is to wait.”

He entertains notions of moving to Chicago or Minneapolis and devoting himself to a theatre company, but for the moment he’s held in place. “It’s like sitting at a blackjack table. To get up and walk away when the next hand could be blackjack.” He tries to put his energy into developing his personal life, including settling in a large one-bedroom, river-view apartment on 175th Street with his girlfriend, Blair, who has just graduated from ART this spring. He’s in limbo, though, “waiting by the phone and putting so many other parts of your life on hold.” Suddenly his ideas about creating a second home for his daughter Gabrielle feel naive to him. He knows that wherever he is, he may have to leave the next day or may have an audition or need to prepare for one. Moreover, every day he “wakes up in a question of livelihood, income, and where I’m going to be.” Nothing he sees holds out a pot of gold. Meanwhile, his eight-year-old may know something he doesn’t. At the end of a summer in California, during which she tapped her own love of acting in a summer program where she appeared as the Polynesian girl in South Pacific, she is asked if she wants to play the main, title character in Alice in Wonderland. She’d rather be a ladybug, she explains, or a butterfly.

There was only one scenario of illness I’d ever consider possible among this healthy bunch: one of the gay male actors contracting HIV. Fortunately, it never came to pass. I knew that Kevin had tested negative for the virus but that, being in a relationship with a positive man, his sero-status was a continual worry. He attended lectures, talked to counselors, and did reading but, in the end, he couldn’t accept the fear. “There’s a gray area you can’t clear. I just couldn’t take that leap.” When they broke up, Kevin was—and still is—healthy.

Caroline Hall‘s sudden illness was all the more shocking for being unexpected. Caroline isn’t the youngest of her graduating class, but, as long as I’ve known her, she has struck me as the most youthful spirit, funny without hostility and unambivalently kind. She’s also the most consistently private of the group, despite her friendliness. From the first, exposing this year to any but her closest friends, went against the grain. So, it becomes doubly incapacitating when she is diagnosed with cancer and told that both her life and her reproductive system could be in danger. Both these early prognoses prove wrong, but her physical problems continue, taking a chunk out of the year. She spends four of the next six months in bed, before and after major surgery, recovers, and suffers complications from the operation, all before pulling through, active again, nearly well, and on the mend.

Basically, what happens is this: During rehearsals for the Lark Theatre‘s truncated Romeo and Juliet (in which she performs with Tom Hughes) she suffers severe pain and high fever. It continues into the first week of Don Juan rehearsals at Columbia. She goes to a doctor who tells her she has cancer. She has to quit the play and stop walking around. She moves in with her mother in Boston. When a new series of doctors find problems but no cancer, she’s confined to bed rest, followed by surgery to remove ovarian cysts, and a month’s recovery. She reads compulsively during her convalescence—Margaret Atwood, Kaye Gibbons, Ann Beattie, Joan Didion—a book every day or two.

When Caroline returns to New York, she starts temping again and gets cast as Posthumous in an all-woman production of Cymbeline that she’s spotted in Backstage, a trade paper for actors. She starts feeling poorly again and the doctor tells her to quit either day work or the play. Since she’s been borrowing money from her parents this whole time (while luckily covered by her father’s business’s insurance), she chooses the $13-an-hour temp job and drops Shakespeare, with regret. Her surgery has caused infections, it turns out, so the temping stops, too. She’s confined to bed for another month.

By fall, with the end in sight, she’s eager to put it all behind her. After nearly five months of silence, she returns my phone calls apologetically and agrees to meet. When I see her I’m stunned by a change in appearance and energy, as if in these missing months, she’s been tempered into maturity. Her hair is longer now and, recuperating, she’s a bit tired. But everything about her—even her humor—seems richer, more complex and interesting. She’s hoping to regain some control of her life, she explains, not that she’s had any since moving here. “I’ve never experienced this before,” she says, “never encountered this open space, this lack of control, this inability to create my own action.”

She continues with an illustration, a vignette about small rewards and their oversized impact on the spirit: “The other day I was going to lunch, but only had $3. I didn’t want a tuna sandwich. I really wanted a turkey sandwich. That day at Blimpies, the special was a Turkey sandwich for $2.99. I was so happy I told everyone. I called my mother. That was as good as it gets.”

A hundred years ago, Anton Chekhov wrote what may still be the single best dramatic portrait of the actor as a young woman. Nina in The Seagull is Chekhov’s anti-romantic antidote to the romanticization of the actor’s life. She suffers the trials of a melodrama heroine. She runs away from a tyrannical father, locks into a romantic obsession and has her heart broken in love and work, before emerging as neither a star nor a corpse but as a dedicated, if ravaged, survivor willing to perform wherever she can and able to keep focused on the small inner voice, “my calling.” Her lesson—that life is more about endurance or sheer stamina than about glory—is an often paraphrased sentiment among this class of 1995 in their year of transition. Many of the women attest to wanting to play Nina, anywhere, anytime. This year, they are, in fact, women and men, all Ninas.

Siobhan Brown‘s transformation dazzles me, though I can’t immediately say what’s different. She meets me in the audition room of Theatre Communications Group. Her hair is frizzy and full, as she’s given up on relaxers. She jokes that it’s the end of assimilation. Are her glasses different? Her hair color? Is she taller? Thinner? Certainly she’s more self-possessed.

Little things have marked the change. She has a permanent part-time job now, at a decent wage. She’s paying her own rent, now that her boyfriend, Carl, is out of town with Stomp. In fact, she’s using the time apart to evaluate this rocky relationship, to build up herself. She’s bought a dresser for her apartment and is staining it. For the first time in New York, she won’t be living out of a suitcase. She’s also just returned from Boston, where she played Titania and Hippolyta in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the first outdoor Shakespeare in Copley Plaza. While there she insisted on her own housing, rather than agreeing to commute from her mother’s house. She started out playing the fairie queen straight but then got freer with the role, in a way that incorporated more movement. The director kept telling her they’d have 1,000 people in the audience, but the number seemed unreal. “The first night I looked out and there were 1,000 people there.” The last night, as the actors moved across the stage constructed atop the drained Copley fountain, the audience barricades reached back as far as the street. She followed this fulfilling production with a family vacation on the Cape, where she spent time alone, on the beach, running. “In my first year in New York I just wasn’t able to do those things for myself,” she explains.

She is beautifully present, in a way I haven’t seen her before. And she’s looking forward. “I can’t wait until I’m 30,” she insists. “That’s why I stopped processing my hair. Oprah says you come into your womanness in your thirties. I feel like I’m coming into something that’s been pounding down my door for a long time.”

I ask her about the year as a whole, its highs and lows. Suddenly, she is weeping. A moment ago, she was joking and confident, in full flower, like her newly natural hair. Now, in this corporate room without windows or character, the year catches up with her. Her crying springs from memory, release, and sheer exhaustion. “As a girl I dreamt about coming to New York, and when I finally do, I’m hopping around with a suitcase and no place to be. It’s just been kind of hard. My sense of home was destroyed.” She cries for a while, one hand shielding her eyes, the back of the other wiping tears away. Siobhan is counting her losses, experiencing the weight of her unique, representative life. Then she looks up again. Her face is sad, radiant, and strong.

Epilogue

“Destiny stands with our dramatis persona folded in her hand.”

—George Eliot, Middlemarch

Nov. 4, 1996. The year (year-and-a-half, to be precise) in the lives of these actors ends today. I have fallen in and out of love with each of them dozens of times since leaving Cambridge. I have been struck by their seriousness, talent, and smarts and been driven crazy by the opposite traits: self-seriousness, vanity, and smart-assedness. I have been jealous of their youth and beauty and irked by their careerism, their me-ism. On occasion, I’ve wished that they were many things they’re not. In other words, after betraying me once by not wanting what I wanted for them—that is, to stay together as an ensemble—they have betrayed me regularly, simply by being themselves.

Now it is my turn to betray them. I will do what any journalist must do—boil them down, sum them up. By putting these young artists into a few paragraphs each, I’ll have to contradict their deepest, actorly conviction that they are infinite, possible—that they can be anything. Moreover, by making them into stories and examples, I’ll be making their lives into mini-romances at the very moment that they’re struggling out from under the mythology of “making it” as an actor and trying to take life as an actual, daily thing.

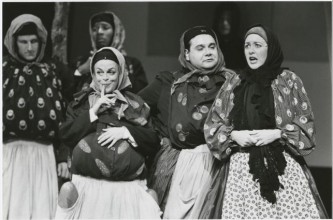

Today they come together for the first time since graduation. They’re easy and nervous, familiar and uncomfortable with each other and with me, as if on the verge of some cosmic opening night. The photographer arrays them onstage at a Soho performance space called HERE, amid all the clichés of backstage life—black rehearsal clothes, a ladder, unhung lights. Their power as a group grabs me again, and my pulse begins to race. I didn’t know them as individuals when we started this project. I knew them as a class, a company, and it was this all-togetherness that elevated each of them and moved me most deeply. Fourteen people in a room, pushing each other to their most creative extremes, under light, in full view. Lean slightly forward, the photographer tells them; it will make you more vivid, as if you are straining to come off the cover, out of the picture.

Maybe it’s the future they’re leaning into. Tom doesn’t know it, but in four days his son will be born. Randall will be spending the immediate future with his new girlfriend, Ela, breaking out of his workaholic solitude. He’ll also be traveling to festivals throughout the world—he’s just returned from one in Moscow—with his one-man Pinocchio 2035. Within hours Kevin will head to Norfolk, Va., on a three-play contract with Virginia Stage Company. Jessalyn is the only one absent. She’s waiting in Montreal for her entry papers. She’s about to land the lead voice in a new animated movie called The Quest for Camelot, opposite Cary Elwes, Gary Oldman, and Jane Seymour. Since the merchandise for the movie was designed before the screenplay was written, she’ll also become a doll—of a young girl who aspires to be a knight of the Round Table. Each of them has someone to become.

When I say goodbye, they’re still shooting. I slip out of the theatre, looking back at them. At the lobby door I turn around again and sneak back to where I can peer in without being seen. They will almost certainly never share a stage again. One last time I notice the way their bodies, having trained together, remember each other, the ways they give and take and seem to gain in stature by some alchemical mix. They are being photographed not as private people or as characters in a play but as actors, distinct and merged the way you are in any community. The flash pops and I move away again. I exit the building and enter into a sparkling fall day in New York, a place, H.L. Mencken wrote, “where all the aspirations of the Western World meet to form one vast master aspiration.” Within a couple of hours, they’ll all straggle out, too, to make their own ways.

This article concludes the three-part “Open Call” series. Parts 1 and 2 can be found here and here.