This is the second part of a three-part series on the 15-member class of 1995 of American Repertory Theatre's Institute for Advanced Theatre Training at Harvard University. The first part—an extended dramatic personae: 15 actors, 15 lives, 15 stories—can be found here. This second part follows the cast of characters as they begin their professional careers, setting out for theatres across the country and abroad, braving the exhilaration and the challenges their work affords. In part three, the young actors offer a candid assessment of the spiritual rewards and material costs of their first year as actors in America. —The Editors

“No one can ever have made a seriously artistic attempt without becoming conscious of an immense increase—a kind of revelation—of freedom.”

—Henry James

FALL/WINTER 1995: Vontress Mitchell looks around the table in wonder. He’s sitting at the Odeon, a quintessentially hip 1980s restaurant in the Tribeca section of downtown New York. It’s a place you expect to spot artist-celebs after hours—Robert DeNiro or Jay McInerney, Deborah Harry or Mary Boone—but you don’t expect to see them sitting at your table. There they are, though, Vontress’s own kind of dream team: playwright Suzan-Lori Parks and actor/writer Wallace Shawn, Richard Price (the novelist and screenwriter who has just finished the movie Clockers), and theatre director Liz Diamond. He thinks to himself: “I’m here. This is going to take a while, but I’m here.”

The “here” in that thought is Manhattan, the city, capital “C” city, to which Vontress and the other 14 actors in his graduating class made tracks when they left the American Repertory Theatre’s Institute for Advanced Theatre Training at Harvard last summer. The transition into New York has been bumpy for him, and he’s still embroiled in roommate dramas that sap his energy and thwart his concentration. For today, however, life feels hopeful. Today he clocked 10 hours rehearsing a benefit reading of Parks’s The America Play. Vontress has the playwright to thank for this energizing day. He met her when they worked on The America Play in Cambridge two years ago and, more recently, she recommended him to Diamond, who is directing the reading. As a student at A.R.T., Vontress was cast in a nameless supporting role, but this time he reads the young lead, Brazil, a man digging in the “Great Hole of History“ left to him by his father.

The audience, which represents to Vontress the “cream of the avant-garde,” gathers in Richard Price’s beautiful brownstone home. The event raises money for a smart arts-and-artists magazine called Bomb. It also puts $200 and a four-year subscription into Vontress’s pocket. He needs the money, but even more he needs creative work and creative company, fuel for what has turned out to be a difficult journey. He isn’t certain he wants to stay in New York, but for the moment he’s rejuvenated, re-committed. He’s having a glimpse.

He’s witnessing something larger than public recognition or the lifestyles-of-the-rich-and/or-famous. Surrounding him are artists whose success allows them to live in their creativity. Their work, unlike that of so much of the laboring world, seems to set them free. What is this freedom? Henry James described it as the revelation that “the province of art is all life, all feeling, all observation, all vision.” If the whole of experience falls within the artist’s compass, if there’s no off limits, then everything becomes a subject for wonder. Maybe, too, creative acts beget more creative acts, and artistic freedom increases with each exercise of that freedom. For actors, unlike artists of many other disciplines, no serious artistic attempt can happen in isolation. Writers can write, painters paint, and musicians play without being hired to do so. But for actors, freedom requires a job.

It also requires risk, whether it’s the colossal risk of moving one’s life to Manhattan and committing years to a potentially disappointing endeavor or the small personal risk of making an ass of yourself for two minutes in front of a casting director. Having quit his day job as a waiter in order to more fully commit to acting, Mark Boyett is already flying without a net. In his callback for Beethoven and Pierrot at Denver Center Theatre Company, Mark, improvising the role of Mephistopheles, gets asked to seduce Beethoven into selling his soul. The piece’s co-directors, Pavel Dobrusky and Per-Olav Sorensen, looking for physically daring actors, push him toward a sense of physical danger. His Mephistopheles becomes a sex-charged southern belle with a demon inside. In the improvised audition, he she throws the deaf composer to the ceiling and dominates him sexually. Mark is offered the part and asked, “Would you be willing to shave your head?”

The fear of appearing foolish doesn’t end with his audition. He’s contracted to make outlandish comic choices in a production whose text will be developed in rehearsal. “Improv has never been my forte,” Mark admits less than a week before heading to Denver, “and now that’s what I’ve been hired to do.” His strategy involves meeting fear with fearlessness. “I’m going to have to put myself out in rehearsals right away. In this business the way to make a fool of yourself is to try not to make a fool of yourself.”

It works. He faces down his fear, and has “hands down the best experience I’ve ever had in the theatre.” In this “unbearably satisfying” collaboration, he improvises from sketches of scenes, listens to tapes of rehearsals, writes lines and jokes and whole scenes of his own until his character has the strongest possible arc. Beginning as Beethoven’s therapist in a simple suit and horns—intent on wresting Beethoven’s soul—he weakens as Beethoven resists. As his relative power decreases, this devil goes to sillier and sillier lengths. He grows a moustache and goatee, wears a skimpy bikini (the belle from the audition finds her way into performance), and sports larger and more grotesque devil parts—huge horns and hooves—before giving up on Beethoven’s soul and settling for a mere dedication. Mark is thrilled by what he learns about comedy. He also gets cast in the next two DCT projects, Brecht’s Galileo and Tony Kushner’s adaptation of The Dybbuk.

Although neither of these productions sets him on fire the way Beethoven did, the consistency of work—nearly seven months of back-to-back acting assignments—allows him to test what he learns, to hone his comic skills and fortify his confidence and ambition. The no-holds-barred lunacy of Mark’s wild ride offers a rare, explosive kind of freedom.

Randall Jaynes, hired in August as part of the replacement squad for Blue Man Group, must find his freedom within the most exacting restraints. His face, neck, and prosthetically bald head are coated in vivid blue. His hands are sheathed in blue latex gloves. His face maintains an almost dehumanized deadpan. His body, at times, is outfitted with helmets, coveralls and tubing that forces creamy crud to spew from his chest. He never speaks. All the while, in what must be the most astonishing set of contraries on any stage today, he and his two cohorts engage in feverish athletic anarchy, an imaginative, futuristic rampaging that weds child’s play with conceptual art, science fiction with primitive ritual and fierce Taiko drumming with game show: They leap balconies, flick endless supplies of candy and marshmallows into each other’s mouths across hefty distances, and beat out “White Rabbit” on PVC pipes. They slip seamlessly from clown silliness into bottomless postmodern irony, from Chaplinesque sweetness to angry battering against the soul-killing technology of the information age. All this without cracking a smile. Still, despite their automata exteriors and the mechanistic clip of their bodies, three distinct, compelling spirits shine through. When Robert Frost characterized freedom as moving “easy in harness,” he might have been describing Blue Man Group.

For Randall, whose courtship with the company began before graduation, the job blends joy and discipline. It also gives him a security that, coming from an economically precarious family, he’s never known. His Blue Man–owned apartment in the East Village comes cheaply, and the company pays for the physical therapy necessitated by 10-minute stretches of full-bodied drumming.

Nevertheless, the job “doesn’t ease 99 percent of what I go through.” Even in weeks where he performs eight shows of an hour-and-a-half each, arriving at the theatre two hours before curtain for makeup and an elaborate sound-check, he struggles with having more down time than he’s allowed himself since childhood. He’s unable to read, unable to fall asleep or to get himself out of bed before afternoon. He spends too much time alone, watching videos, shell-shocked or obsessing over solo performance projects, missing “normal life other people, a lover.” He makes a list of all the people he’s tried to have relationships or even dates with and tries to “figure out what the fuck’s wrong with me.”

Randall’s personal discontent, standing in contrast to his professional success, combines the pain of leaving home and carrying it with him. He describes his family life as an aquarium, suggesting a strange, sealed life underwater.

His father died in the spring of Randall’s first year at ART from a lifetime of deterioration, alcoholism and what Randall calls “sensitivity.” Unable to maintain a work life, despite intelligence and humor, Mr. Jaynes lived for some years as a virtual shut-in. Randall’s mother, a relentlessly hard worker, became the family bastion. Randall sees himself as a blend of the two, and his current life, alternating as it does between enervating solitude and driven workaholism, gives supporting evidence. Blue Man’s members meet on off days to brainstorm new ideas and to collaborate on each other’s outside projects. This extra frisson makes Randall even happier to have entered the group’s ranks. Nevertheless, he’s more preoccupied by his inner landscape and his self- generated work—specifically The Birdcatchers and what will become Pinocchio 2035—because they connect so deeply to his personal concerns. Clearly, though, Blue Man has returned him to the aquarium life. With its multicolored tubing projecting from the walls and spinning plankton-like from the Astor Place Theatre’s grid, the environmental setting even evokes a world submerged.

This circling back must be one of the motifs of an actor’s life. The necessary introspection of their work keeps memory stirred up. The dysfunctional processes of theatre recreate those of many original homes while the actor’s nomadic life adds the feel of continual recurrence. Furthermore, by some strange almost supernatural set of convergences, certain plays and people keep meeting up again. Vontress’s one-night reunion with The America Play is an example. It’s a play that comes double-loaded with memories of professional satisfaction and personal trauma.

One day, during the rehearsal period for the ART production, the institute administrator sought out Vontress at home. She came to tell him that his brother Corky (Cortez), the youngest of seven sons and closest to Vontress in age, had been shot and killed by the Wichita police. Vontress flew to Kansas, where the questionable circumstances of Corky’s death had created a cause célébre, catalyzing law suits and a vigil march in his memory.

According to Vontress, Corky had a current harassment suit pending against the police and had won a previous case. The white officers claim to have stopped the young black man on a traffic violation and to have shot him only after he fired on them. Vontress numbers the bullets in his kid brother’s body as nearly 20. Corky was driving a ”wonderful bright red jeep” when he was pulled over and, apparently, the police thought he was a drug dealer. He wasn’t, though, Vontress says; his baby brother was just spoiled. “My mother bought him the jeep.”

Their mother, a devout Baptist, went into a deep depression. (Their father, whom Vontress has only seen once, lives in California.) Vontress’s trauma is evident from the painful contradictions in his telling: “I came out of it really well. I’m an adaptable person. I took it the hardest.” After the funeral, he had to return to ART and The America Play, in which he enacted a ritualized assassination of a faux President Lincoln, shooting him repeatedly and at close range. He doesn’t return home for two years.

Now, as he reads the part of a man poking around in his ancestral dirt and coming up empty-handed—a gaping absence of history that extends to African-American culture at large—Vontress is simultaneously set free from the difficulties New York has strewn in his path and routed back to the hole in his own history. When another brother’s wedding draws him home to Kansas in early spring for the first time since Corky’s slaying, he intends to gather information, to interview his family, and to begin filling in the missing pieces by making art, a one-man show about the incident. But, at least for now, something about being there deflects him from probing further.

Digging is one metaphor for acting. Actors must tunnel down deep into their own emotions and histories and hoist up the most striking, relevant finds. (This is the part of acting that’s been emphasized by the American method.) Filling up is another metaphor. Actors fill up with energy and character, as though they’re vessels, into which a character’s spirit is invited. They also fill external forms, roles or physical scores or styles. To do so they must become larger, radiate out, like genies released from bottles. Actors, I think, must maintain these contrary energies, digging down and filling up, inward and out, listening to themselves and attuning themselves to others, planting their feet on the ground while their majestic skulls float atop their long, ready spines. Maybe this counterpull is what attracted me to this particular group of actors. Unlike those maddeningly imbalanced actors who seem too self-focused or too outward-projected and showy, these 15 seemed evenly attentive to themselves and alive to the world.

Jessalyn Gilsig navigates these contrary extremes with an almost electric conviction. More than her striking looks or distinctive voice, Jessalyn’s indelibility as an actor springs from the density of her engagement with character and text. As Lavinia in a student-directed production of Titus Andronicus, for instance, she translated her character’s rape and mutilation (her hands and tongue are cut off) into a savage expressiveness. Her Andromache in The Trojan Women: A Love Story workshop was a ferocious-funny portrait of someone both imprisoned by and rebelling against the protocol of upper-class womanhood. The wit and fury that infused this performance were literally splashed across the back wall of the stage every night in a sprawling mural she painted from scratch during the first act of each show. Attacking an expanse of brown paper in hysterical response to the trauma of Trojan ruin, Jessalyn became actress as action painter, digging in and flinging the colors of her soul onto a larger-than-life canvas. Scraps of these murals now hang in several of her ex-classmates’ New York apartments.

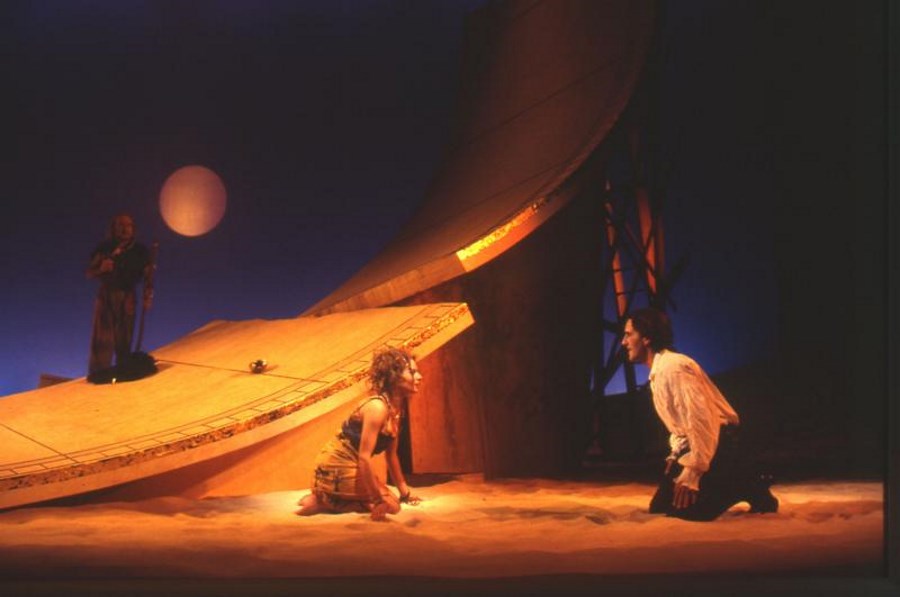

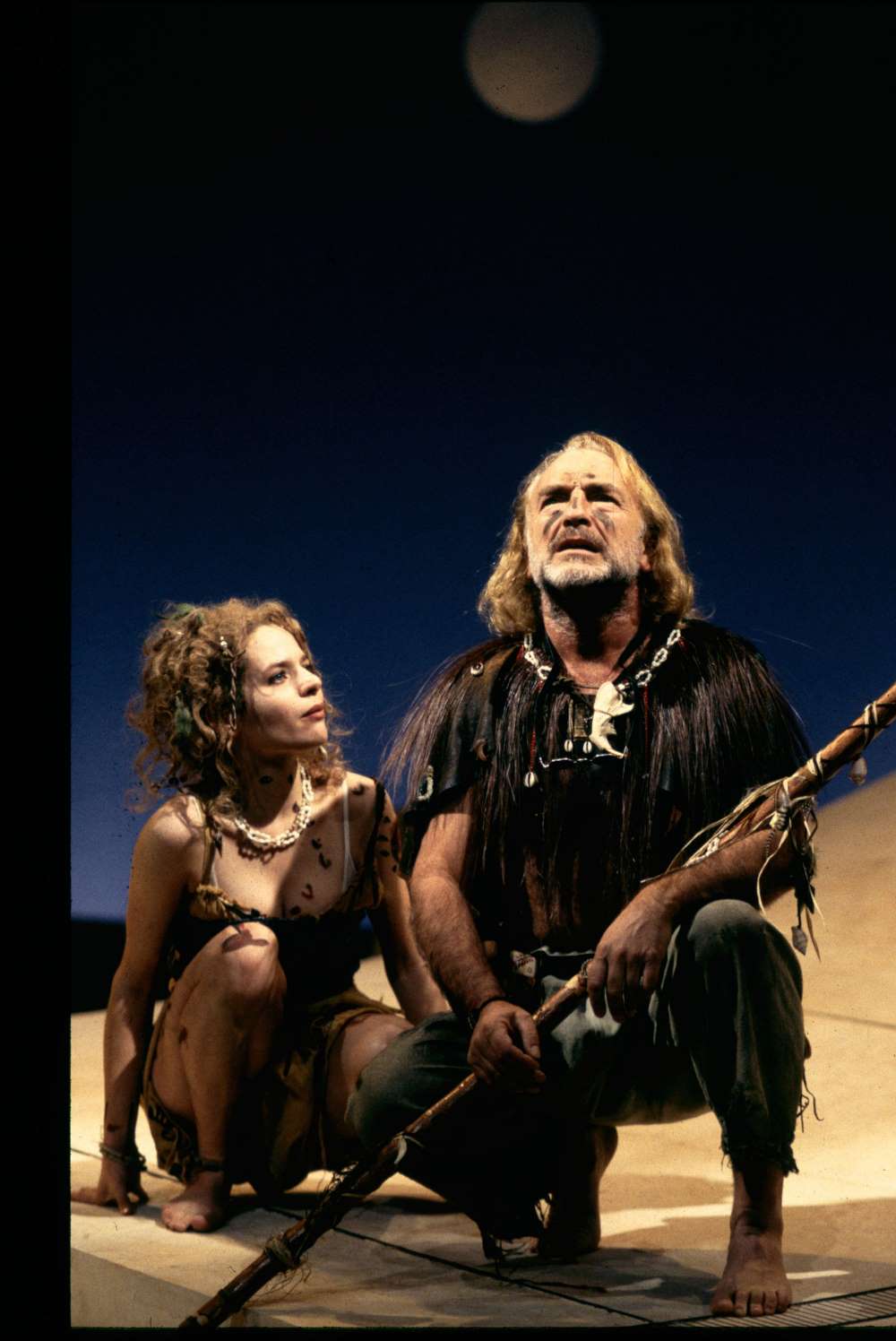

For all the complexity of her portraiture and her feminist perspective, when Jessalyn circles back to ART’s professional company, she goes as a pure ingénue. Both Miranda in The Tempest and Marianne in Tartuffe are sheltered young women at the threshold of awareness, neither having faced hardship, much less the horrors endured by the Greek and Roman heroines Jessalyn played during her final student semester. (This will also be true of the two potentially career-igniting roles she lands after moving back to New York later in the season.) Still, her identification with these roles is intense. At the end of performances as Miranda, “I thought I should just disappear like Miranda disappeared.“ Part of this specific intensity comes from being the only woman in the cast, a position that adds unnecessarily to her overwrought sense of responsibility, as if she needs to come across as an Everywoman because she’s the only woman.

This self-imposed burden is relieved in Tartuffe because the four women’s roles cover so many aspects of a woman’s experience; Jessalyn feels free to focus on the story. By now, too, she’s stopped worrying about proving worthy of her new, non-trainee status. “I was really intimidated at first. I thought, ‘all these first-year students probably think they can play Miranda.’ Then I thought, ’They will play Miranda.'”

Not surprisingly, then, back at the theatre where she trained, her experience is defined in large part by her shifting relationship to her former teachers. She’s worked with both of her directors before. Ron Daniels, who oversees the Shakespeare production, ran the institute during her tenure, and she’s almost romantically drawn to his conviction about ideas and to his perceptions about texts. Francois Rochaix, guiding the Molière, is more formal; there’s little personal connection. Rochaix tries to shake up her preconceptions about period style and about being an ingénue. She has a hard time letting them go. Some days she’ll feel herself beginning to cry as he speaks to her; he just keeps on talking. She’s developing a real respect for the other actors she knows who bounce from job to job, now that she sees how lonely it can be. She takes solace in the company of the other women. Although she’ll leave ART feeling that, because she went to school here, this doesn’t count as a real first job, she knows how fortunate she is. Each night during bows for Tartuffe, she stands with Tommy Derrah, a former acting teacher of hers who’s playing her father. She takes his hand and thinks, “I’m so damned lucky.”

Not every job offers personal enlightenment or freedom. When James Farmer first reads Olympia, by the Hungarian playwright Ferenec Molnár, he doesn’t get it. It seems thin, emotionally superficial. He’s grateful to be working at Actors Theatre of Louisville; it helps justify the painful year of enforced separation from his new wife, Tracy. Nevertheless, even once rehearsals begin, once the play comes into focus—its mean streak, rigid caste system, and emotional subversion—he’s still groping, just finding his feet as an actor. He leans on the director too much. Even in performance before appreciative audiences, he can’t seem to “make it mine,” except in moments. Right now, he’s still suffering from the student’s self-consciousness; he hasn’t yet recovered “the joy of playing.” A Christmas Carol, in which he plays Young Scrooge, among other things, holds out no hope of deep fulfillment either. The Dickens chestnut simply demands “being cheerful about Christmas for an hour and a half.” In his first winter of work, everything feels middling. He lives (without Tracy) in the Mayflower, apartments converted from an old hotel in downtown Louisville. Initially, he thought it would provide a funky pleasure, “like Camino Real. But now it feels more like the Betty Ford Clinic.”

Kevin Waldron finds his work on Room Service at Denver Center Theatre no more transcendent. Mark Boyett is still there, living on the floor below him, and that’s a salve for the loneliness of itinerancy. The leap into broad comedy, though, is unsettling. He’s playing Harry Binion, the play’s second banana, “the real cynical one who has all the funny one-liners, all the zingers.” He thinks Groucho Marx played the role in the movie, but, since the director discourages the cast from watching the film, he’s never seen it. Instead, Kevin rents His Girl Friday and other screwball comedies to get a sense of the genre’s rhythm and style.

By the fourth day of rehearsal, the play has been fully staged. By the end of the same week, the cast is off book. For the remainder of rehearsals, the actors run through the show once each morning and once each afternoon. Kevin is used to a different kind of scene analysis and breakdown, but senses there are professional boundaries in place that he should respect. Over the course of the daily double run-throughs, he finds comic bits getting stale from constant use. These he discards for new ones, which, similarly, lose freshness. His character is dictated, to a certain extent, by the exaggerated black-and-white costume; black riding boots, jodhpurs, beret, and riding crop. “I’m playing him big, primarily because my costume was so big.” He’s directed, for instance, to enter at one point, take center stage and say, “The rehearsal was terrific!” while slapping (and, of course, hurting himself) with the crop. Sometimes, the play works and is fun. And other times “it hurts to be onstage. It’s like having egg on your face.” Gnawing at his consciousness is the job he backed out of to take this one.

Options, which are luxuries that few actors enjoy, create anxiety. They can also create ethical dilemmas, situations in which personal freedom and responsibility collide. These dilemmas can be as straightforward as the escape clause in a contract or as knotty as friendship. The choices actors make resonate through the theatre at large, which dictum sometimes seems to be: “You can’t trust actors to commit. They’re always on the make for something better.”

During our first interview, in Cambridge a year ago June, Ajay Naidu said something that scared and shocked me. I mentioned that his classmates seemed suddenly ambivalent about leaving each other’s company, fearful of the imminent future, even confused what to hope for. “Bullshit,” he said, without malice. “They all know exactly what they want.” Was he right? Are their aims so solitary? In the ’60s and ’70s , when professional nonprofit theatre was taking root in America, the idea of art theatre was practically synonymous with “acting company.” Is the myth of young actors making history in a church basement now history?

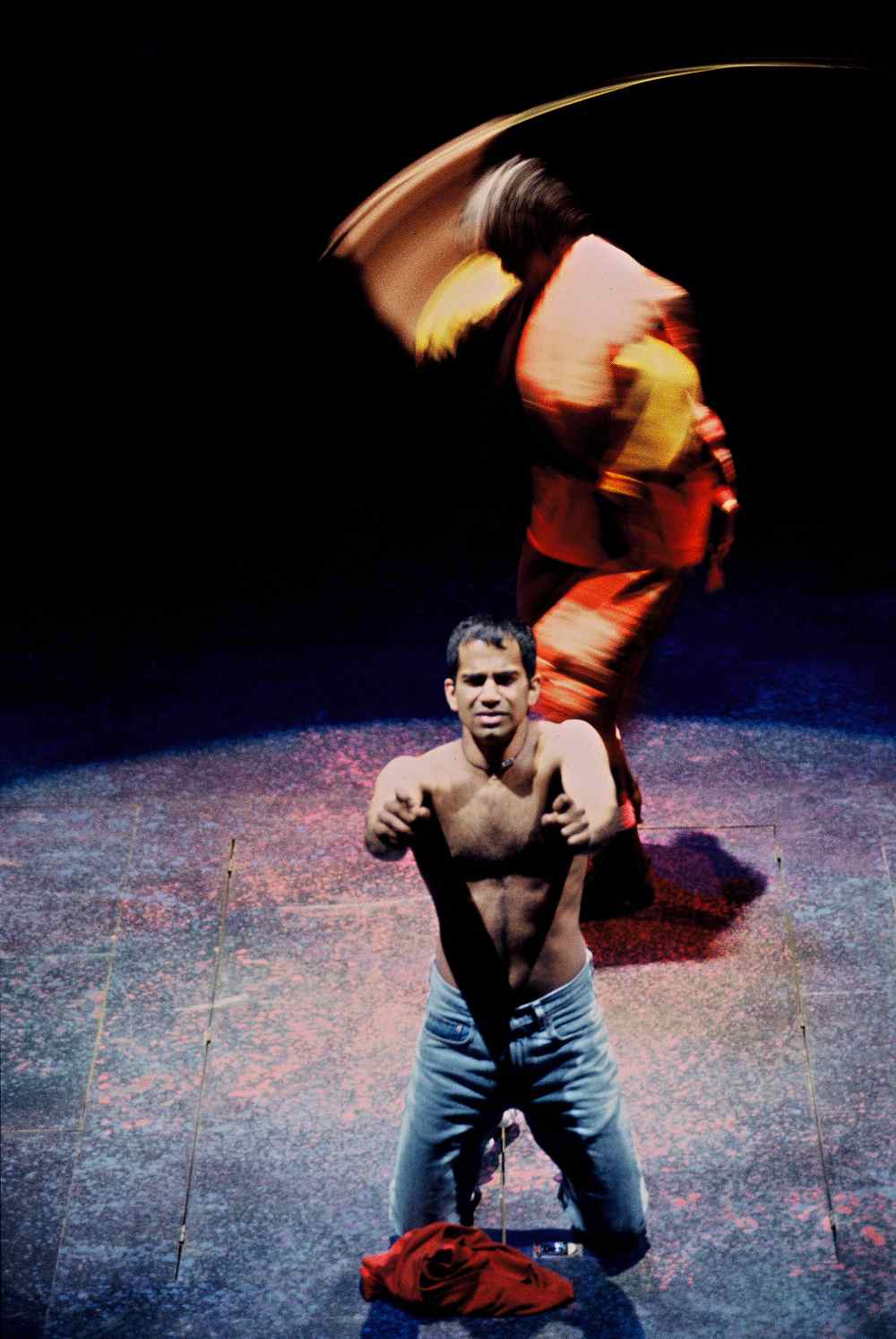

Ajay is not usually this harsh. He’s very sweet. The first time I saw him he was massaging a friend’s shoulder so tenderly I assumed (wrongly) that they were lovers. As a performer, he is polished, athletic, and direct; he smacks of confidence and drive. He arrives at our first New York interview with flowers for my family. It’s a charismatic gesture, combining genuine affection with flattery—a pitch for approval so transparent it’s endearing. He knows I will ask him about Denver, where he is rehearsing Paris in Romeo and Juliet before he left, and about Steppenwolf, where he will soon begin work on Everyman.

Ajay has accepted a job in Chicago as an ensemble member rotating into the lead in the famous medieval morality play, directed by his friend and earliest theatre advocate, Frank Galati. The timetable as he tells it: When Ajay is two weeks into rehearsals for Romeo and Juliet, Galati, who “ups the ante on my career regularly,” calls him and offers him a job without an audition. While he’s considering the offer, his mother phones with the news that his father, an emergency room doctor with a history of diabetes and two open heart surgeries, is ill; they’ll be moving back to Chicago soon. The she says “the magic words: ‘If you can find work in Chicago…’ I wasn’t going to leave,” he says, “until I found out my parents would be there.” He remembers his sister’s mental illness and blames himself for not being with her enough before her suicide.

He calls his agent and authorizes him to say yes to Steppenwolf. He asks the agent when he should give notice. With a four-week out in his contract, it makes sense to give notice four days before the first preview. He will then leave three-and-a-half weeks into the play’s run, one-and-a-half weeks before it closes. By disclosing at this time, he hopes to earn both credits for his resumé and spare Denver some hassle. The agent sends a fax giving his father’s health as the reason for departure and the Steppenwolf gig as incidental, but in retrospect Ajay thinks this too equivocal. “They should have said it was my dad. Period. Or Everyman. Period.“

The DCT administration replaces him immediately, before the show’s director leaves town. They put the sub in at first preview, Ajay believes, “to make an example of me.” Ajay helps train his replacement but can’t claim the role in his credits. He watches the initial preview and flies out the next morning. “I don’t think I’ll ever do it again for anything, except perhaps a major movie role,” he admits, somewhat concerned that his classmates will think he made a bad political decision. It’s not worth the guilt, he explains. Moreover, he likes to finish what he starts.

I find myself pushing him for a more complete mea culpa: Did your father’s health really decide it? How guilty do you truly feel? What would happen if everyone broke commitments like this?

When he hits Chicago, Ajay is home. Everyman serves up the kind of aesthetic fulfillment you dream about. He’s ecstatically happy. He stays with his girlfriend’s parents, works on a one-man show about Indians living in America, turns onto a new music called “jungle,” and even starts to design his own line of dance clothes. His parents haven’t moved here yet, but they’ve bought a house in nearby Gray’s Lake.

Kevin Waldron is faced with, and makes, a similar choice, but it takes him in the opposite direction—to Denver. He is initially scheduled to play the lead in Phyllis Nagy’s Weldon Rising, directed by a colleague from ART, at the small Coyote Theatre in Boston. He has a verbal agreement that includes a little pay; he also has a burgeoning friendship with the director, with whom he’s been discussing the play for months. There’s little chance of a conflict, since he hasn’t been auditioning much. Anyway, he’s vowed not to back out. Kevin notifies the agent he freelances with, gives the show’s dates, and tells him to expect a contract. But then a Room Service audition he’s sent on goes well, and Kevin phones Mark in Denver to find out more about the theatre. (Mark, incidentally, would have overlapped with Ajay, if Ajay had stayed.) Mark tells him the show’s dates; they conflict with Weldon, the director of which is out of the country. There’s still no contract in hand for the Boston production (a common non-occurrence in the world of small theatres) when DCT offers him a part. Having left several messages—never responded to—for his friend in Boston, Kevin accepts the Denver offer. They haven’t spoken since, though it’s trickled back to Kevin how angry and disappointed he is. The director has only 11 days to recast and reconceive the play’s major character.

Both decisions raise ethical questions, and neither actor takes these lightly. Kevin lacks a contract when he jumps ship; Ajay bails out midstream. Is either one more or less “wrong”? Is Kevin’s choice more acceptable because he trades up in pay (he’ll make approximately five times as much at Denver)? On the other hand, Ajay played only a secondary character in Romeo, while Kevin was the key player in the Boston project. What does a director do when they lose the Hamlet 11 days before rehearsal? How far in advance would Kevin’s reversal have been okay? Ajay, as it turns out, does the right thing for him; his Steppenwolf experience is joyful. After the fact, Kevin harbors little doubt that he chose the less challenging work, but upon returning to NYC, his agent signs him, a move that leads to additional work. What are the boundaries of commitment: money, friendship, contracts?

Siobhan Brown, Kevin’s classmate and friend, is also cast in Weldon Rising. She stays with the show, returning to her hometown for the second time since graduation to play a “lipstick lesbian,” a less central role than his. For her, Weldon is a positive experience—good work well received. It also leads to an even better one: playing Titania in an exciting outdoor A Midsummer Night’s Dream in Boston’s Copley Square, produced and directed by the same man. Loyalty and talent are, in her case, rewarded. But what assurance do actors ever have of such rewards?

One of the long-lived mantras of American theatre training programs is, “Create your own opportunities.” The stacked odds against steady employment for actors makes this valuable advice for every decade, advice this group of actors heeds with a vengeance. Chandler Vinton enlists an actor she and her mates admire to start an acting class. It fizzles after a few meetings, through no fault of Chandler’s. Different combinations of actors surface in a series of projects, many involving other ART alums. These include 15-minute “Monarch Notes” Shakespeare plays, directors’ laboratory projects, student and small independent films, and even student-directed plays at other New York City grad schools.

Todd Thomas Peters and Caroline Hall are cast in a production of Odon Von Horvath’s Don Juan Comes Back from the War at Columbia University, directed by a masters student who saw them at ART. You have to keep acting, Caroline explains. “You get creaky. You have to do it. I’d rather be in a bad production than in nothing.” When a postcard for Don Juan arrives at my house in early spring, though, Caroline’s name has disappeared and Chandler’s has been added. Todd claims to be doing better than he thought he’d do to reach his goal of 100 rejections by year’s end. He’s logged about six failures so far, he says. He also continues to develop The Birdcatchers with Randall, after their successful performance in Venezuela. He and Caroline talk about starting a business “to sell something to somebody.”

Caroline joins Tom Hughes with the Lark Theatre Company, an educational outreach group that mounts a 50-minute, four-actor version of Romeo and Juliet to tour city schools. Tom teaches for Lark besides. Vontress begins meeting with a theatre—information he finds in the trade paper Backstage under “membership.“ Almost by accident, he’s a founding member of what wants to be called Lone Wolf.

Sherri Parker Lee hooks up with a devoted, enthusiastic band of actors she meets through a regular customer at the restaurant where she waits tables. ”Coach,” as he’s called, is one of four customers in the place during the record-breaking blizzard of ’95-‘96. “My son has a theatre company,” he tells Sherri. “You should call him.” Sherri, scouring Manhattan for a theatrical home base, is constitutionally incapable of ignoring a lead. She calls. Coach’s son casts her as Lydia Languish in the Habitual Theatre Company production of The Rivals. They enjoy a “fun” run in a supportive atmosphere. When the steam pipe at their theatre breaks before their closing-day photo shoot, four or five members of the nascent company empty the building and call everyone on the sold-out list for the afternoon’s performance. They nudge the show from 3 to 5 o’clock, get down on their hands and knees and clean the theatre, salvaging everything they can, after which they assume the manners of the 18th century before a grateful audience.

Suzanne Pirret is beginning research on a one-woman play about the life of Edie Sedgwick. Mostly, though, she’s thinking about L.A. “Everyone of my friends that is out there is working and seems happy,” she says. “Here in New York everyone is complaining—just like me. Everyone here is self-deprecating and discouraged. Everyone’s on Prozac.” She visits Los Angeles in mid-January, meets an agent and a guy from ABC, all through friends. Ideally, she’d like to move there, she explains, “make a name for myself, come back and do theatre—good theatre.” It’s hard, though, especially having been around this same block before, to keep her confidence up.

While they work, look for work, and make work happen, while they search for that revelation of freedom, life keeps going. Kevin, who began dating an HIV-positive man in November, something he has avoided in the past, waits for his own test results to come back from the lab. Jessalyn, home from ART, watches the clock run down on her Canadian visa. Caroline, whose name has dropped off the cast list for Don Juan at Columbia, stops returning my calls—weeks, then months of calls. I hear she’s very sick. I hear she’s left town, then I hear she’s back. Still no contact.

Granville Hatcher lands his second job as an onscreen terrorist, a Jordanian this time, and shuttles between Manhattan and his daughter in Boston. Tom Hughes becomes the Elder’s Quorum President for his new Mormon congregation close by his Washington Heights home. Also, after many months of orthodontia, he gets his braces removed, a necessary step toward commercial work. Todd Peter’s marriage plans—made almost entirely without his input—roll along their juggernaut way.

At 4:30 on March 11, Ajay phones. He’s edgy, waiting to hear about something “very big—major,” but he can’t tell me what. At 6:45 he calls back, “feeling stoned with excitement.” He just book a lead role in the movie of Eric Bogosian’s SubUrbia, directed by Slacker whiz Richard Linklater. A few days later, Tom’s biggest dream begins to come true: “We’re having a baby,” he announces. “We just decided to start, and boom!”

Next, in Part 3: The spiritual costs and rewards of acting.