“This century found it necessary to invent Woyzeck,” a critic wrote in 1972. The statement, at first perplexing, has proven true again and again. Woyzeck was probably written in 1836, less than a year before Georg Büchner’s death at age 23, but it didn’t effectively exist in theatre history until Eugen Kilian staged the world premiere in 1913, and since then it has often served as a vessel for other artists’ ideas. In 1925, Alban Berg adapted it into the opera Wozzeck, which became more widely known than the play. In 1969, Ingmar Bergman used it to start his controversial “open-rehearsal” program at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. Joseph Chaikin acted the title role in 1975, after a seven-year absence from the stage, in a production incorporating many ideas from the Open Theater. And now, Richard Foreman—in a directing project that seems, in retrospect, inevitable in his career—has found it necessary to invent Woyzeck at Connecticut’s Hartford Stage Company.

In effect an honorary 20th-century artwork, Woyzeck holds a special place in the modern consciousness. Based on an actual case from the 1820s of a common soldier who murdered his lover after learning she’d betrayed him, it is generally considered the first drama to deal with a protagonist lacking any social status or dignity whatsoever. It could be called an Ur-underdog story, written before anyone cared about underdogs, and its major themes are ageless: the injustice of a universe that seems to require the victimization of man, and the absurdity of notions such as madness, sanity and normalcy in the face of that cruelty.

Even more important for our era, however, has been the history of the manuscript, which was found in a bottom desk drawer as an unnumbered jumble of scenes, apparently unfinished, perhaps intentionally abandoned; it had to be treated chemically before it could be read. We are fascinated by its long concealment and its long neglect after reconstruction, largely because theatre people considered it too gloomy to produce, and we are fascinated by its fragmentary nature, the fact that even the ordering of its scenes is uncertain.

The fragmentary has been a constant motif in our century, but few artists have been more articulate about its nuances and vagaries than Richard Foreman, whose essays and manifestos quaver with a nervous energy remarkably similar to Woyzeck’s. Early on in his career, Foreman spoke of searching for an “atomic” structure that could replace conventional dramatic development. He wanted to break down stage action into “the smallest building-block units, the basic cells of the perceived experience of both living and art-making.” Today, by his own admission, his work “operates in terms of larger building blocks than it did years ago” (“I’m getting older and mellower,” he says), but his work in Hartford nevertheless suggests a lode of affinities between director and text, of which the fragmentary is only the superficial tip.

Will this production be ruthlessly avant-garde, like one of Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theatre productions? Spoken or not, this is the question on everyone’s mind at the first rehearsals. In an interview, he answers without being asked. “In spite of what some of my critics have said, I do not believe in taking classical texts and trying to turn them into one of my plays. I believe in just doing the play and not getting in the way, too much. Of course, a lot of people attacked me for Don Juan”—which he directed in 1984 at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis and at the New York Shakespeare Festival—“for exactly the opposite reason, but I think they’re wrong. I think that I was serving Molière when I did Don Juan, but people said, ‘Oh, he must hate Molière.’ Well, to me Molière is the greatest writer ever for the theatre.”

Lest his comments be misunderstood, though, Foreman adds that for him serving a writer means first of all serving oneself. “Something that has never interested me is having a career as a director where this year I do my version of The Three Sisters, and somebody compares it to his version and his version, and you sit there trying to figure it out, well, how can I do it a little differently, how can I make my contribution?” What, then, is his attitude toward the text? He says he believes in complete fidelity, “but obviously you can only be faithful to the collision of your particular interior world with the world of the text. I certainly don’t believe in any kind of archeological faithfulness, like Peter Stein.”

And why this particular text? “Woyzeck is one of the few plays that I find bearable,” he says, “mostly because the language is so sparse. I don’t mean that there’s little language and lots of action. I mean the syntactical forms themselves—these imaginative leaps that happen in the language. That’s what excites me in all literature, in all language, these leaps from idea to idea where you sort of jump logical steps, or you jump from category to category. It’s totally that particular stylistic use of language. I mean, as far as the first tragedy about a poor little guy,” he goes on with a quick laugh, “that’s fine, but we’ve seen that. That’s not even too extraordinary.” His reasons for choosing Henry Schmidt’s translation follow this same line of thought: “It seemed to me to have the greatest leaps in it, the greatest tension of that kind of language. All the other translations I read seemed to smooth out the language and make the speeches progress in an evener way, a more logical and romantic flow.”

Must Woyzeck function for him as an exploration of the workings of consciousness, as do his own plays? “It sort of does when I read it,” he says. He doesn’t believe, though, that his staging or set design for the production will be “avant-garde” in any drastic sense, and he doesn’t think that the artist’s consciousness, as manifested in the character of Woyzeck, is in any way esoteric. “I don’t know if I would these days call it an ‘artist’s consciousness,’” he adds. “I think it’s the consciousness of someone who is striving to make himself more lucid, better, more awake. To me, the play is about: Where does the language that one speaks, the ideas that one expresses, come from? It’s about clairvoyance in a way. Everybody’s groping for some way to make sense of chaotic, turbulent forces that they’re confronted with.”

And the fragmentariness? Among his first remarks to the cast before the initial read-through is: “The truest and most incisive thought for our time must be aphoristic thought. Thought in fragments. Fragments appeal to us. Fragments are relative to the situation we’re in because the world, in a sense, if it’s not falling apart, at least it’s mixing up, ready to give birth to something else.” He elaborates on this point and others in a document with the characteristically talky title “3 Things I make myself remember while working on WOYZECK,” written for the program, but he doesn’t refer to it now or at any point in the rehearsals I attend.

Only David Patrick Kelly, who plays Woyzeck, has worked with Foreman before, and the tension in the room is palpable at the start. Privately, I’ve asked several of the actors what preconceptions they had about Foreman. “You name it, I heard it about him,” said one. Another said sulkily that he assumed Foreman was “like one of those European guys” for whom the actor “isn’t really a collaborator.” The more the director speaks, however, the more they all relax. His talk is remarkably practical-minded, and he plunges into ideas only after dropping a startling comment: “I have no idea how to do this play.”

He wants the cast to know that the benefits of Woyzeck’s strange, almost supernatural insight somehow apply to all of them: “The very things that Woyzeck says, the very way he uses his language, puts us in touch with some basic building blocks in our own unconscious, in our own spiritual orientation, and I think we can find that. I think we’ll be able to find that truth for all the rest of you miserable screwed-up people in this play.” Also, he wants everyone to understand that the drama, for all its depressiveness, for all the suffering it depicts, is ultimately redemptive. “Sometimes evil is the

gasoline that ignites something that drives through an insight, or a way of looking at things, or a realization. It is of use to humanity in the long run.” And finally, he offers the simplest, most pragmatic reassurance of all: “I’ll tell you honestly, one of the reasons I was interested in doing this play was that it’s short, which should result in us having sufficient time in these four weeks.”

The allotted time turns out to be sufficient indeed, even if some of the heady goals of the first few rehearsals do have to be compromised along the way. After two weeks, the most obvious departure has to do with those

“leaps” and “jumps.” Many attempts have been made to preserve a sense of the play as fragments. For instance, an extension of the scene between Woyzeck’s two chief tormentors, which contains the famous line about Woyzeck “running through the world like an open razor,” has been tried and discarded. “It didn’t work,” says Foreman. “It just seemed as if we were trying to make it into a full-blown dramatic development when, in fact, it’s like a series of haikus. Something is said, you sort of catch it, and then it’s gone.” Despite such efforts, there is an increasing cohesion in the action, and a strong source of it is the background music, the tape-loops that have been playing almost constantly since the first minute of the first read-through.

As much as anything else, these loops, with names like “Ringtone,” “Violin Squawk” and “Yid Circus,” are a sort of Foreman signature. They are used throughout rehearsals for all his plays, and many are retained for performance. Each one is distinct, but they have in common an obsessive, plangent pounding of the same sound, which actors, over the course of several weeks, cannot help but internalize as a form of tonal direction. In Foreman’s own plays, the nonlinear scripts protect against this tonal direction transforming into an unwanted harmony. But disjunctions aside, the action in Woyzeck is linear and sensible, and a certain kind of harmony arises on its own, without the director’s blessing or permission.

Another source of the increasing smoothness, or seamlessness, is the actors’ psychological work on their characters, which Foreman, to nearly everyone’s surprise, encouraged at the outset—but which now seems to be getting in his way. During the first few days, there were discussions about the behavior of lower-class women like Marie (Woyzeck’s lover) in 19th-century German society, discussions about the social status of the Doctor and Captain, discussions about Büchner’s views on superstition and radical politics—all extremely specific and sensitive to what actors ordinarily perceive as their needs. “That went away fast, though,” says William Verderber, who plays the Drum Major. Foreman was apparently torn between a very real fascination with the play’s fictional world and his long-standing ambition to deconstruct dramatic fictions. Thus, as time went on and the outlines of his version became clearer in his mind, he began telling the actors more and more exactly what to do.

Gradually, despite scattered grumbling, they adjust themselves to Foreman and develop, if not an understanding, at least a respect for the integrity of his searching process. He continues to make some rather unusual requests. To Kenneth Gray, who plays the Captain: “Maybe if you had a limp leg. If we could get a massage of the leg that looks weird, like twisting it or masturbating it.” To the whole cast: “Whenever you turn your head, or turn your body toward someone, always complete the turn, as if you’re always screwing yourselves into the stage.” But the actors now know that these things will be summarily dispensed with if they don’t work, and all directions are taken in stride with an air of quizzical trust. Foreman is a ruthless self-editor, and his intense, almost monastic, focus (along with his tape-loops) has set a general tone for rehearsals.

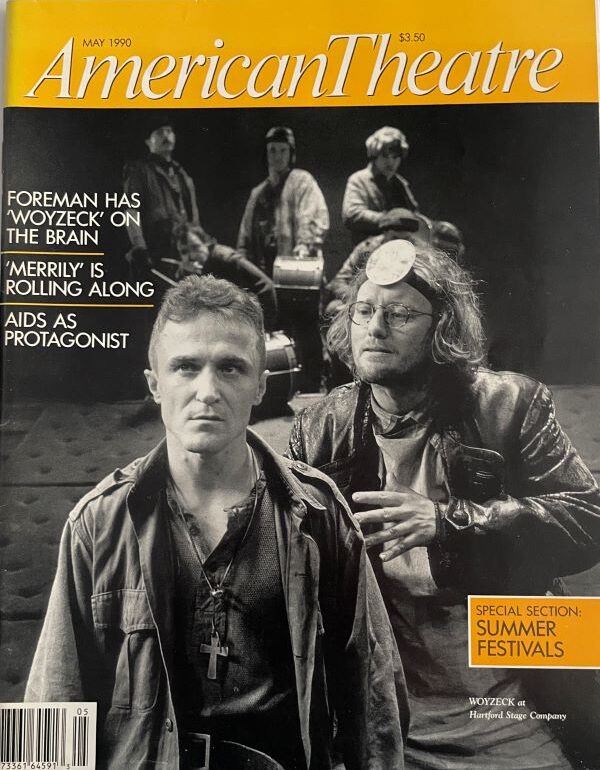

Tracey Ellis, who plays all the female roles other than Marie, says the actors are trying hard “to become the painting he sees in his mind,” and their efforts are plainly evident onstage. Their respect for Foreman is really the flip side of a growing self-confidence; for it has become obvious that the show is impeccably cast. Kelly, with his slightly haggard cheeks and knife-straight facial lines, has already reached a level of intensity uncomfortable to watch. Spinning and skittering about in short, jerky movements, waving his arms, he seems always to be thrashing in flight. Gordana Rashovich, who plays Marie, is equally laserlike, with an air of inner agitation and torment that eliminates any possibility of audiences seeing her character as an ingenue. Both she and Ellis convey a strong and troubling sense that things are not all right with them, deep down, and never will be. And Michael J. Hume, the fraudulent Doctor, is already playing near performance tempo, with a manic insincerity that epitomizes the carnival atmosphere pervading the production.

In his free time, Kelly sits apart from the others, exercising or looking at books from a heap that includes Goethe, Nietzsche, Lenz and others. I ask whether his separateness is a regular habit. “Oh no,” he says. “It’s just that I’m almost always onstage, so when I do have a moment I like to sit over there and look at my Goya.” His most significant discovery over the past few weeks, he says, “has to do with the impossibility of Christian love, or agape.” In a sense, Woyzeck is doing Marie a favor in killing her, because he is “ridding her of the burden of having to deal with this sinful world.” I ask if he is playing a character who understands everything he says, and he answers “yes.” Foreman has spoken of Woyzeck as a conduit, someone through whom insight flows, but Kelly feels he can create that impression only through a process of understanding, and Foreman has given him the freedom to find his own way.

As for the others, the director has finally come clean and admitted that there are really only two “fully dimensional characters” in the play; the rest are more or less cartoons. Woyzeck and Marie are “discordant,” he explains, switching metaphors, whereas everyone else constitutes “this choral fact that they’re trying to escape.” The revelation is unpopular but ultimately helpful. As actor Steven Stahl says: “Until then we didn’t really understand why we were always walking around so morose, like zombies. It helps to know that the people around this guy with all his great insights are just totally down and dirty and comprehend none of it.” After an exhausting run-through, Foreman says: “I hear a lot of you struggling with the intention of your lines, trying to do something fresh and unusual, and that’s good, that’s good acting. But I’d like you to think of yourselves more as trying to get out of the way and have these words come through you.”

He tries to describe the quality he’s looking for, mentioning the French filmmaker Robert Bresson and his practice of using non-actors in leading roles to create peculiar schisms between word and apparent intention. “Try to get a sense of what a sad world this is,” he says. “I still have the feeling that a lot of you are feeling an obligation to make more happen than has to happen. Your presence counts for more than what you do with your lines. You just have to be saturated with the world that produced him. Try to savor the syntactical joy, the syntactical weight of the words. Just let them reverberate in your head without your having any effect on them.

Upon entering the theatre for the performance, the first surprise is Woyzeck’s setting, particularly for anyone familiar with the way Foreman typically outfits a stage. He had said at the beginning: “For many years I’ve been doing plays that are overloaded with props and dreck and I’m trying to do this very simply.” I had seen a scale-model of his design, which he called “a kind of theatrical laboratory bullring dissecting room constructivist machine.” None of that prepared me for the desolate emptiness of this black space, which sucks up light—white, for preference—as absolutely and indifferently as Woyzeck’s surroundings suck up his words.

Outlining the small thrust stage is a low, U-shaped ramp, inside which a semicircular flat space leads to a steep rake and, atop the rake, another flat playing area with an angled ceiling. Most of the floor surfaces are padded, all are black, and a wall lined with white, tile-like squares occasionally flies in and out upstage, leaving an impression of a psychiatric cell. Lining the edge of the U, however, are tall, thin, black poles with bulbs on the ends that suggest street lamps and leave a non-institutional impression of a deserted highway or alley. Numerous other references also come to mind—a boxing ring, an examination room, a stage—but dominant always is the loneliness and colorlessness. The air of desolation is mitigated only by a few skulls, taut strings and rusty chandeliers, which hover up near the flies like a composite logo conveying that complete abandonment of the Ontological-Hysteric was never Foreman’s intention.

The second surprise is the extent to which the director has succeeded in achieving his much-discussed “zombie” quality, the sense of a truly unwashed mass, with a group of actors who, two weeks earlier, still seemed conspicuously healthy and college-educated. Only now do I fully understand what Foreman meant in rehearsals when he spoke of this ubiquitous, menacing chorus of dull-witted people. The faces of the 10 performers comprising it are made up in ghoulish white with red eye sockets. Their presence generates an ambient fogginess—despite the plentiful white light, you’re never quite sure if you’re seeing everything clearly—which eventually reads as a metaphor for the impenetrable fog between Woyzeck and everyone around him.

Strangely, it’s this very fog, this background of unclarity, that sets Woyzeck’s isolated condition in a meaningful frame. No question of madness whatsoever, his visions are indeed a form of insight, clarity. The impression is that his eyes are too much open for his own good, and he isn’t safe in his world. A capacity for real feeling is a liability where numbness is the prevailing ethos, so he becomes a victim through a process that seems almost automatic, natural. Foreman denies him and everyone else privacy onstage; no one is ever alone. In every scene, someone looms in the background, someone left over, or arrived early, or someone listlessly eavesdropping for no apparent reason: Woyzeck’s friend Andres shuffles around on the upper platform during the scene between the Doctor and Captain; Karl the Idiot and a little boy lounge about on the rake during the scene where Woyzeck gives Andres his personal effects.

On the one hand, the extraneous people are calculatedly distracting: They make it difficult for spectators to concentrate on Woyzeck’s romantic poetry without immediately recalling the disagreeable truth about his world. On the other hand, they serve as visual segues, helping to propel the 67-minute action forward with a smoothness even greater than what I had seen at rehearsals. Woyzeck’s crushing understatement about what has happened to him, “One thing after another,” could also summarize the breakneck pacing and the choreographed movement. Scenes fit together like collapsing tubes, and a ritualistic sense of tragic inevitability soon builds around the coming catastrophe—a sense, I notice in passing, totally at odds with the bulk of Foreman’s theoretical writings.

This tragic propulsion is also partly attributable to the cohesiveness of the small, tightly knit choral group. For instance, due to budget restrictions, the Grandmother’s strange set piece of the tale was given to Karl the Idiot, played by Brian Delate, a decision that seemed at first unfortunate because the surprise of the story’s morbidness is lost if it’s told by a character we expect to be morbid. Delate makes it into such a moving cameo, though, that it ends up seeming like a fleeting moment of genuine self-knowledge, or sanity, not only for him but also for the world he typifies. A few others don’t fit so neatly into the package: Hume’s theatricality, for example, is now far beyond the median level, as if, having found the right attitude for the Doctor too early, he started distrusting it and fell into overacting. Gray, however, plays the Captain with a maniacal, Nazi-like machismo I had never seen at rehearsals, and his shaving scene with Woyzeck is now one of the production’s weirdest sequences. He is a large, fair-skinned, blond man with slicked-back hair, and when he’s covered with a sheet and sprawled over backwards on a chair nailed to the center rake, he resembles a pig awaiting slaughter.

Holding it all together is Kelly, whose performance is one of those rare gifts that come along once or twice a decade. Kelly is the opposite of a conventional leading man, short, quirky, unhandsome, violent-looking yet something of a nebbish—in short, the perfect Nobody—and Foreman makes fine use of his idiosyncrasies, taking innumerable choreography cues from the way he manifests Woyzeck’s chronic strain: the tense neck muscles, the darting eyes. The best example is the production’s most lasting image: Kelly lying upside-down on the rake, convulsing rhythmically as he says, “Stab, stab the bitch to death? Stab, stab the bitch to death.” Similarly, when he actually stabs Marie, he comes up behind her and does it in quick, sharp jabs, after which she rolls logwise down the rake and a dozen blazing klieg lights all but blind the audience. The action convulses itself beyond visibility, as it were, an example of the “basic metaphysical paradox” Foreman has spoken of. “There’s some other energy that you cannot fathom, cannot scan,” he says, “so the more you try to see things clearly, i.e., more light, the more invisible the truth of the situation becomes.”

Kelly’s performance is, in fact, so central that it ends up suggesting that the play really contains only one “fully dimensional character,” Foreman’s earlier statement notwithstanding. In rehearsal, Rashovich’s intensity seemed as if it could easily have been a match for Kelly’s, had Büchner given Marie a bit more to say and do. As the play stands, though—especially in this relatively short version—the actress playing that role cannot help, but become a part of the “choral fact.” For one thing, she understands Woyzeck as little as the others do, and for another, as Rashovich’s performance demonstrates, doing justice to Marie’s bewilderment and simplicity means sacrificing much of her prominence as a lead. The occasional stare and gelid tone of voice, no matter how resonant, hasn’t a hope of competing with Woyzeck’s sweeping expressive range.

The real revelation in the production, though, is its reaffirmation of what we knew all along about Woyzeck’s unique openness, its adaptability to widely differing ideas about theatre. Foreman did try to serve the text, and to that end he sacrificed many of his theoretical ideas, but some of them crept in anyway, as if the text itself had called them back. There was, in the end, despite the logic and fluidity of the action, a strong flavor of “pearls”—Foreman’s traditional framing devices that create what critic Kate Davy once called “a sequence of static pictures,” his version of Gertrude Stein’s “continuous present”—implying an affinity with the material deeper, perhaps, than even the director imagined. Ironically, the seamlessness ultimately served him as a framing device; for it made the audience all the more anxious to catch and examine the dozens of immaculately staged moments that were continually flying by.

The resulting amplitude of those details—a momentary glimpse through a doorway of Marie and the Drum Major dancing, brief cut to a pinspot on Woyzeck’s “double-vision” speech—brought with it a pathos that extended beyond the fictional story. It’s as if the ephemerality of the theatre event were made part of the subject matter, and the impossibility of catching it all became the key to a more essential fragmentariness that was poignantly preserved.

And oddly, as with the isolated “pearls,” this effect was ultimately given extraordinary impact by being framed by its opposite. In the last scene, Kelly, after running three complete laps of the stage at full speed, winds down to a stop near some loose boards in the U-shaped ramp. Lifting them, he finds pools of water underneath, into which he slowly wades, mumbling, and the play’s frantic, even panicked, action comes to final rest amid the contemplative sound of lapping water.

Jonathan Kalb, a 1989-90 American Theatre Affiliated Writer, supported by the Jerome Foundation, writes theatre criticism for The Village Voice and other publications. He is the author of Beckett in Performance (Cambridge University Press).