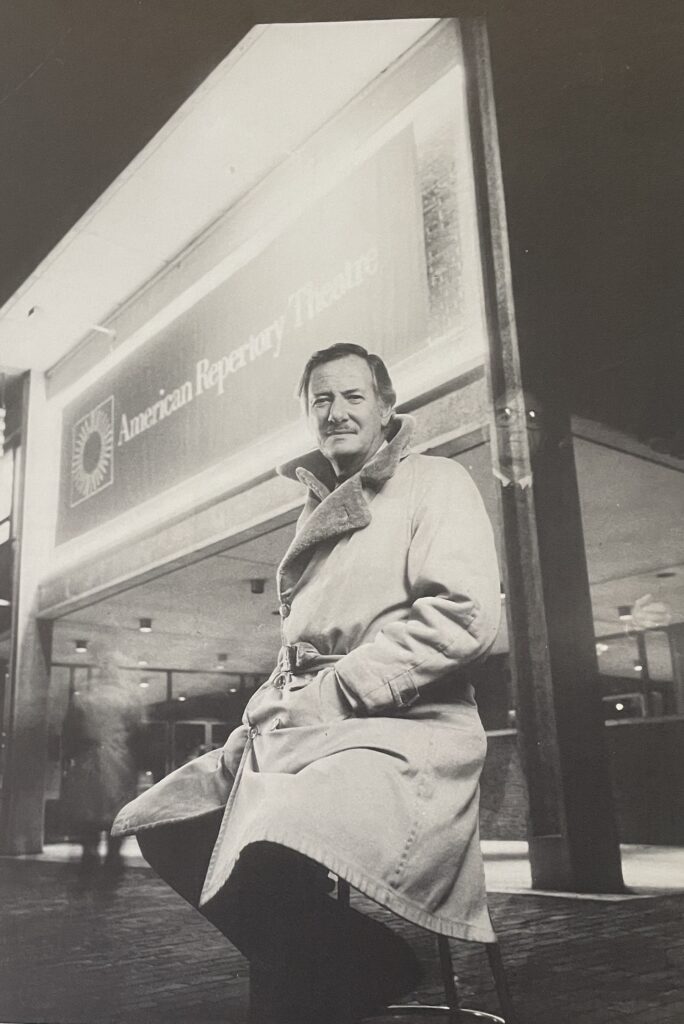

He’s “a man who wears several hats,” it has been said of Robert Brustein, but in his case the expression doesn’t quite fit. Unlike most people who perform more than one function in their professional lives, Brustein doesn’t take off one hat and put on another when he changes roles. He tends to wear his entire collection of headgear all at once. This was never more evident than when he appeared in the production of Luigi Pirandello’s Tonight We Improvise that opened the eighth season of American Repertory Theatre in Cambridge, Mass. last fall.

The evening began with Brustein onstage as an actor addressing the audience in the role of the tyrannical director whom Pirandello named Dr. Hinkfuss. As the author of ART’s contemporary adaptation, however, Brustein had renamed the character “Robert Brustein,” and as director of the production he had this character assume a familiar, professorial tone with the acting company, many of whose members were indeed past and present students of Brustein in his role as an educator. All of this, of course, took place at a theatre which Brustein founded as artistic director and presides over as paterfamilias. There are few individuals in the American theatre similarly situated to write, direct, perform and produce their own work. And in his role as drama critic for The New Republic, Brustein would be remiss if he failed to mention this rare concentration of personae in his end-of-the-season wrap-up.

At the age of 60, Robert Brustein is one of the few distinguished men of American letters who has devoted his life exclusively to the theatre. And he started his hat collection early. Born in New York City, he pursued acting for more than a decade—studying at Amherst College, spending a year at Yale Drama School, and working with an Off Broadway company called Studio 7 and Group 20’s Theater on the Green in Wellesley; he auditioned for Joseph Papp and lost the role of Richard III to George C. Scott. Meanwhile, he also stayed on the academic track, completing a master’s degree and doctorate in dramatic literature at Columbia, studying at the University of Nottingham on a two-year Fulbright scholarship, and teaching at Cornell and Vassar. In 1959, disappointed after an earnest stab at a professional career, he gave up acting and joined the faculty at Columbia. The same year, he began writing for The New Republic, where he has been drama critic off-and-on ever since, winning the George Jean Nathan Award in 1962 and remaining—especially after the death or retirement of Harold Clurman, Kenneth Tynan and Eric Bentley—one of a very few serious, respectable theatre critics in America.

In 1966 Brustein accepted an invitation to become dean of the drama school at Yale, where he was responsible for creating Yale Repertory Theatre and turning the school into the finest training institution for young actors in the country. Dismissed from Yale after 13 turbulent and fertile seasons, he took the core of the company to Harvard University, where he founded the American Repertory Theatre in 1979.

Already a seasoned veteran before moving to Cambridge, Brustein has in just eight years made the ART a triumph, winning the 1986 Tony Award for best regional theatre, landing one of the National Endowment’s prestigious Ongoing Ensembles grants, and attracting capacity audiences season after season. And he has done so not by resting on his laurels as an elder statesman of the resident theatre movement but by exerting a remarkable artistic adventurousness and genuine intellectual leadership. The ART has represented America in annual tours abroad, and has contributed considerably to mainstream theatre—it presented the world premiere of Big River before William Hauptman and Roger Miller’s award-winning Mark Twain musical went to the La Jolla Playhouse and then to Broadway, and its productions of Jules Feiffer’s Grownups, Marsha Norman’s ‘night, Mother, and Eugene O’Neill’s A Moon for the Misbegotten also proceeded to New York. In addition, the ART has produced powerful new plays—Robert Auletta’s Rundown, Hauptman’s Gillette, Norman’s Traveller in the Dark and Christopher Durang’s Baby with the Bathwater—that have gone on to productions elsewhere.

Simultaneously, Brustein has made the ART a haven for the most exciting and inventive stage directors of our time. Landmark productions such as Lee Breuer’s Lulu, Andrei Serban’s Three Sisters, JoAnne Akalaitis’s Endgame, Peter Sellars’s stagings of The Inspector General and Handel’s Orlando, and Robert Wilson’s productions of Alcestis and the Cologne section of the CIVIL warS have fearlessly explored the scary edges of contemporary theatrical art. Performed in rotating repertory, the shows in an ART season will frequently provide variations on a theme such as men vs. women or the search for God in a faithless world. Its current season—which features Richard Foreman’s staging of Arthur Kopit’s End of the World With Symposium to Follow, Ronald Ribman’s new play Sweet Table at the Richelieu, novelist Don DeLillo’s first play The Day Room, and Dario Fo’s Archangels Don’t Play Pinball, directed by Fo and Franca Rame, as well as the Pirandello—touches on several aspects of the self-reflexiveness of today’s culture. (Yuri Lyubimov’s production of The Master and Margarita has been postponed.)

When this interview took place in January, Brustein was at the peak of activity. He was performing several nights a week in Tonight We Improvise, stepping up his fundraising efforts as part of a new effort to provide the ART with a $5 million endowment, and overseeing the company’s brand-new Institute an Advanced Theatre Training, aimed at developing new acting, directing and design talent for the ART. At the same time, Brustein was recovering from two severe bouts with pneumonia; he had taken to wearing a surgical mask around the theatre to protect himself from everyday microbes, and he would in February undergo surgery to have a benign tumor removed from his lung. We met at his home in Harvard Square, a big comfortable family manse with evidence of grown kids around: ski boots on a rack by the door, a Eurythmics album by the stereo. (His sons Philip and Dan are both in college; his wife Norma died in 1979.) The conversation began in front of the fireplace and continued over a chicken casserole prepared by his housekeeper Olive. Easy-going yet sharply articulate, Brustein exudes an unmistakably patrician air that can seem arrogant, avuncular, comradely and humble by turns. The conversation ranged from the subject of non-traditional casting (“All else being equal, I would prefer to give opportunities to good black actors over good white actors”) to Brustein’s fetish for science-fiction movies (2001 is his favorite, followed by a British film called The Creeping Unknown).

It’s been said that the ART is the most European of American theatres, certainly since Liviu Ciulei left the Guthrie. Do you think that’s true, and do you have a European model in mind?

I think it’s true that we’re more European—Rumanian or Russian or German or French—than English. It’s significant that we don’t do Stoppard, we don’t do Shaw, we don’t do Wilde. We don’t normally do a very verbal and technical kind of play. I think that critics, including myself, have been more prone to honor their own discipline, which is language, than to recognize that the theatre is made up of a great variety of expressions. I almost sound as if I’m parroting what I say as Hinkfuss in Tonight We Improvise, quoting Meyerhold: “Words in the theatre are design on the canvas of motion.” But you know, if you have a theatre in which vou only attend to language, then—again as I sav as Hinkfuss—you could just stay home and read the script. The most exciting theatre to me has been a theatre that uses all the arts of the stage, and maybe that’s why I lean toward European theatre rather than English.

It sounds like your thinking about this has changed, that at some point you became less interested in plays and more interested in production or the visual aspects.

From the very beginning, we were interested in three kinds of plays. First and foremost was the new American or European or even English play. Second was the unappreciated classic, one that had been left on the shelf whose time had come. Third was the familiar classic—the anthology classic—but only if it could be seen in a new way, refreshed. So I don’t think we’ve changed our policy in that regard at all. And if you want to know the theatre that we originally based ourselves on, it was probably the Berliner Ensemble rather than the Royal Shakespeare Company or the National Theatre.

When you say “from the beginning,” it’s unclear whether you’re talking about the ART in Cambridge or the Yale Rep.

Clearly the beginning of this theatre was in 1966, when we first started the Yale Repertory Theatre.

Except that when the publicity says the ART is celebrating its 20th anniversary, anyone who can count to seven remembers that the ART started in Cambridge in 1980. And there’s a Yale Repertory Theatre that continues to exist now.

Well, there’s a Yale Repertory Theatre building that houses work being done by Lloyd Richards. But how do you identify a theatre? Is it the building? Or is it the people? Or the ideas that happen in that building?

The tricky part is the “we,” because most of the people here weren’t working in the Yale Rep in 1966.

You’re right, so I have to refine the idea even more and say it is the idea itself which is the continuity, and that idea has not changed in 20 years. We have one actor who has been with us for 20 years—that’s Jeremy Geidt. Our managing director has been with us since 1969 as a student, that’s Rob Orchard. Our publicist Jan Geidt’s been with us since 1966. If we kept actors that long, they’d be doddering.

But isn’t the acting company what defined the Berliner Ensemble?

No, that’s the Moscow Art Theatre. The Berliner Ensemble is really defined by Brecht’s idea of the theatre.

So what unites the years you were at Yale and the years at the ART is your idea of what the theatre should be.

It may have been given form and impetus by me, but it’s a collective idea, and it was reached by the collective throughout the years.

You wear several hats, being an ongoing critic as well as an artistic director. How do you deal with the conflicts of interest?

Simply by announcing them whenever I feel I’m in one. I reviewed ’night, Mother, and I called the review “Don’t Read This Review.” I announced my conflict of interest in the first two or three paragraphs and said don’t continue reading, but I have to talk about this play that I think is important. In general, I have to find what I hope are honest strategies to let people know that I am implicated in some way. When Harold Clurman was reviewing on The Nation, he knew a lot of actors and directors, and the way he dealt with this problem was by being very kind and very compassionate. I was pretty rough and judgmental in those days and judged him for being so kind. I think I’m being judged in many of the same ways today. I’ve heard people say that I am a promoter for the avant-garde, that I am too kind and compassionate to people like Robert Wilson.

Well, people have grumbled about how you’ll promote Ronald Ribman as the heir to Tennessee Williams without mentioning that you have been a champion of his plays as artistic director here. Do you feel sensitive about declaring your interest?

My prose can get very clumsy if I have to announce parenthetically every time I mention somebody’s name that he was my student at Yale in 1977 or we did his play at the ART in 1982. I don’t do it all the time, that’s true. The fact is that I have been associated with a lot of people who are now functioning in the theatre in one way or another.

Do you think that impairs your freedom or your credibility as a critic?

No, because I know I’m going to tell the truth. The only thing it can impair is my friendships. There are things that I choose not to review, things that are too close. I didn’t review Big River, for example. But I’m in a position where I don’t have to review everything. My magazine has me down to one review every three issues, so that means I can be selective.

Do you worry about offending in print people you would like to have work at the ART?

Well, I worry about it, but ultimately I don’t fudge.

Do you have any thoughts on the state of criticism at the moment?

Other than the fact that it stinks, no. There was a time when criticism attracted a lot of really brilliant people. With certain exceptions, it doesn’t now.

Do you think a situation exists where critics who came along with the caliber or substance of an Eric Bentley or Stark Young or yourself would be employed now? What would they write for? Vanity Fair?

There has been a diminution of outlets, and even those who are long-time regulars find themselves being squeezed. I don’t resist too much, because how much is there to write about? Although I’m being unfair. If I had the time and I could go around the country, I could write every week about interesting and exciting productions. What we’re missing is that itinerant critic who will go anywhere to see something exciting.

I’m very taken by your idea of the roving repertory critic, but do you think the possibility exists?

Why doesn’t The Village Voice do it? Why doesn’t The New York Times do it? That’s the real scandal.

Actually, both Frank Rich and Mel Gussow travel somewhat.

Yes, Frank Rich got very upset with me when I said the Times doesn’t travel except after a new play that might come to Broadway. He pointed out that there’s a lot of traveling going on. For example, he went to see Lyubimov’s Crime and Punishment at Arena Stage in Washington on the night that a Broadway play opened. I think that may have been the first time in history a Broadway play was not covered by their first-string critic, who was down seeing a play at a resident theatre in Washington. That signified some difference. But still, there isn’t half enough. A lot of very exciting stuff by Ciulei and Pintilie at the Guthrie was never seen by The New York Times. And exciting things in La Jolla, things in San Francisco, things at Trinity Rep in Providence, which should be covered a lot more than they are.

Part of the question is, does theatre criticism matter these days?

Well, that is a real question. At the moment it doesn’t. My next book is called Who Needs Theatre [We both laugh.] It says in effect, you need theatre. But it’s kind of whistling in the dark to say that, because most people think they don’t need theatre. That’s because they’ve got television. They have much more comfortable forms of dramatic entertainment. What they’re talking about is rabbit warrens: they’re holing up inside their houses with no access to community, no access to the world, to the street, the vitality of outside. That’s not the only terrible thing about not needing the theatre, because what they’re getting in its place is dreadful. It’s empty, vapid.

Why would you say they do need theatre?

They need theatre in order to confront the basic spiritual, political, intellectual and emotional issues of the day. It’s the only place where there’s still freedom to hear those things. I’m not talking about the commercial theatre, certainly. But the commercial theatre now constitutes a very small portion of theatre in this country. The possibilities in the other areas are quite remarkable. I continue to be a booster, much to the chagrin of my fellow critics, in saying this is a remarkable time in the American theatre. I know that from the seat of my pants. A remarkable time for playwriting and directing. Everything but acting.

You think it’s not a good time for acting?

It’s a great time for acting, but the actors are not in the theatre. They’re somewhere else. The other people can’t leave the theatre. Even though David Mamet can write a Hill Street Blues or The Verdict, he’s stuck with the theatre. It’s a disease in him, and it’s a disease for directors to direct. It doesn’t seem to be a disease for American actors to act on the stage.

It’s been noted that though you’ve been able to attract many of the best directors in the country to the ART, you haven’t had as much luck attracting really great acting talent. A lot of the best actors have come for a season, perhaps two, but not remained part of the company.

Well, actors are basically itinerant in this country—gypsies who move among the various media, film, television and theatre. Until this year, our company has consisted of seven or nine people. That’s what we’ve been able to afford. With the expanded company grant we’ve gotten from the National Endowment, were up to 15 actors. That’s full strength for us, compared to 150 at RSC. Ken Howard is back with us after being my student in 1967. He called me and said he wants to come back and act. You respond to that sort of thing. Talia Shire called me—she wanted to come back.

Somehow this is not quite on the caliber of Meryl Streep and Christopher Walken. Don’t you find it a frustrating situation, not having all the actors you could possibly want at any given time?

I find it frustrating that actors will not leap to play a juicy and impressive role with a director who’s going to stretch them. Acting is an area that can bring you extraordinary fame and wealth. Or it can bring you extraordinary artistic satisfaction. It can’t bring you both. Agents are continually telling the actors that theyre stupid to look for creative satisfactions when they could invade the dreams of Americans and be very rich and have wonderful houses and all the goodies of American life. The American actor continually sells his soul year by year for these advantages.

However, the American actor got into acting because he or she recognized the artist in himself or herself. So I don’t think that’s the end of the story. There are actors who want to work on the stage but they won’t come back and work in permanent companies over a period of five to ten years. They can never give up that global world created by the movies and television. If you just bring them in for one or two shows, then it causes resentment in the rest of the company who have made a sacrifice to be here. Not that much of a sacrifice, because you can guarantee 52 work-weeks a year to an actor, at salaries ranging from $450 to $800 a week. Yet we keep apologizing that we’re not paying hundreds of thousands of dollars, which is what they can get for a movie. It’s too bad. I think the values are all topsy-turvy, and it depresses me. But if you want to know why companies in this country are not acting companies, that’s the reason.

Is there anything you can do to try to change that?

I’ve tried every possible thing you can do. I’ve been a guilt-producer, Ive inveighed, Ive screamed, I’ve cuddled, I’ve cajoled, I’ve wheedled, I’ve offered free room in my house, I’ve given meals. I’ve done everything to try to persuade actors that their future lies with doing great roles and not doing garbage. You can get somewhere temporarily, but you can’t get anywhere permanently. You’re fighting a system. The American capitalist economy is essentialized in the acting profession: the alienation of the worker from his work, the exploitation of the worker as long as the worker is useful, then you throw the worker away.

Speaking of cajoling and inveighing, you have a stellar reputation for fundraising. The Boston Phoenix recently said something like whenever you sneeze, some corporation offers $60,000 so David Byrne can score it, Robert Wilson can stage it, and Newsweek can send Jack Kroll to review it.

I wish that were true.

What’s your secret? What rap do you use with people that works?

The fact is that—this is something I should never admit—I rather enjoy fundraising. I believe in my theatre deeply, and it’s not hard to communicate my own enthusiasm for it. We’re serious and we’re also very well-managed, which is a very important and underestimated aspect of fundraising.

It’s very important for funders to perceive that the money they provide is not being wasted, that the company is not exceeding its means, that it does everything in its power to make the books balance. That’s impressive to businesses, who tend to think of artistic enterprises as being flaky and essentially irresponsible. We are a wonderfully managed company because of Rob Orchard.

How does he make a difference?

He takes a close look at the dollar, but he is an artist himself and will always spend that dollar to improve the result. If he thinks that holding onto the money is going to have a deleterious effect on the quality of production, he’ll take the leap. On the other hand, he is not going to let any extravagant spending take place because one director sees that another director has a terrific set and he or she wants a set that’s equally large.

You’ve said in print that after the first couple of shaky seasons, you’ve achieved the audience you want here in Cambridge. How was that accomplished?

I’ve also said that my big mistake after that second season, when we lost half our subscribers, was looking at the 7,000 people who left us instead of looking at the 7,000 who stayed. The ones who stayed were our audience, and it’s on that basis that we built.

How do you nurture your relationship with that audience?

Well, by remaining as adventurous as we can. That’s what I feel to be my obligation to this audience, even though there are many of them who feel they’ve had enough adventure and let’s have a conventional play, please. This is a very intellectual community. They want to deal with texts. I knew when I came here that their favorite playwrights would be Tom Stoppard and George Bernard Shaw. I could never lose if I put on those plays. That’s really what the Harvard University audience would like. They’re interested in things of the mind, which is not surprising, not unusual. I’m interested in things of the mind, too, but I’m also interested in the imagination and that’s what I’ve been trying to extend and probe and palpate. That’s the unexpected.

What changes do you feel have taken place in playwriting over the last 25 years?

Playwrights today approach life in an entirely different way than they did in the days of Arthur Miller and Clifford Odets and Tennessee Williams. It’s a non-linear, non-causal universe that they’re calling up in their plays. My beef about playwriting, particularly American playwriting, from the ’30s to the ’60s was that it was all pre-planned, therefore predicated. Cause A inevitably led to Effect B. I think we’ve been more and more dicsovering that that’s not the way the universe happens.

It seems odd to say this, but there was a time when progressive, optimistic views of the world totally dominated all our literature, particularly our drama. It made our drama a travesty. When Bertolt Brecht was performed in this country in the ’50s by Carmen Capalbo in that long-running Threepenny Opera, it was done as if it were Pal Joey. It was cheerful, it was upbeat. The notion of us understanding the German despair—the German rot and deterioration and association of the human flesh with butcher shops—was incomprehensible up until the ’60s and ’70s, when that idea began not only to invade but to dominate our consciousness. Now of course we need a reaction to that. That’s one of the things affecting American playwriting and making it better. Generally speaking, there is an admission that surprise is one of the main constituents of existence. That nothing is predictable. Be prepared for the unusual.

You’ve been either credited with or blamed for introducing the notion of dramaturgy to the American theatre. What is the importance of dramaturgy?

It depends on the kind of theatre. If they’re just going to do the staple anthology repertory, you need someone to paste the program together, but you don’t need a dramaturg. The dramaturg is part of the whole critical intellectual apparatus of the theatre. And since critics and intellectuals are not generally prized or valued by working professionals, it’s important for people to get to know that they’re not a threat but rather an aid to the apparatus.

Do you have a sense of what influence this idea of dramaturgy is having across the country?

I think it waxes and wanes. Two things happen in a time of poverty, when funds are short. First of all, the dramaturg gets fired, and secondly, the vision of the theatre shrinks to what the artistic director thinks the audience wants. Those two things are related, because the dramaturg—if he or she is worth the name—is constantly trying to push the artistic director and the theatre to take more chances, to be more daring. My perception right now is that dramaturgs are still very much in demand, but a lot of them are giving up positions and moving on to other things.

Could you critique your performance as artistic director of ART? What are your strengths and what are the areas you could improve?

You catch me at a time when I’m feeling singularly self-satisfied, because we have the institute in place, and that’s something I’ve worked for for seven years now. A very important link in this chain has been finally forged. To be perfectly honest, I could be better-natured—I’d prefer to lose my cool less often than I do. And I’d like to have more family relations with the actors—more dinners, more parties. They really have become my family, and it’s a pleasure to be in their midst. The older I get, the more paternal I get, and I feel that many of them are my children, and I enjoy watching them develop and grow and even leave. I’m privileged in that regard, to work with people that I love in a profession that I love doing the kind of work that very rarely humiliates me or shames me.

Don Shewey’s latest book is Caught in the Act: New York Actors Face to Face, a collaboration with photographer Susan Shacter published by NAL Books.