When Laurence Olivier hired his most astute critic, Kenneth Tynan, as dramaturg of England’s National Theatre, he joked: “I’d rather have him inside pissing out than outside pissing in.”

This August the Mark Taper Forum’s artistic director Gordon Davidson followed Olivier’s example when he appointed Los Angeles Herald Examiner drama critic Jack Viertel as the dramaturg of the 742-seat Centre Theatre Group/ Mark Taper Forum. Viertel was simultaneously hired as a consultant by CTG/Ahmanson artistic director Robert Fryer to develop original musicals for his 2,000-seat theatre.

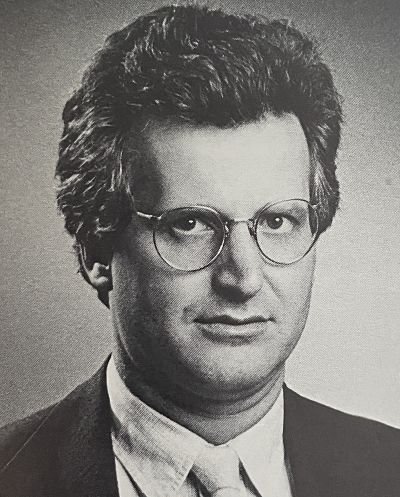

The 36-year-old Viertel had been reviewing Los Angeles theatre for seven years, the last four with the city’s second-largest daily newspaper, the Herald Examiner. During that time, Viertel’s critical reputation spread nationally. In a New York Times interview, Big River producer Rocco Landesman credited Viertel’s “scathing pan” of the musical’s La Jolla premiere with having generated the improvements leading to its seven Tony awards. Viertel was also the first Los Angeles critic to champion those “bad boys of magic” Penn & Teller, and the subsequent New York production—a continuing hit at the Westside Arts Theatre—was co-produced by Viertel’s brother Tom, heretofore in the real estate business.

Despite Viertel’s reputation, Davidson’s choice to fill the vacancy left by Russell Vandenbroucke’s departure caused a stir throughout the southern California theatrical community. The primary reason for the astonishment was that Viertel had always been the Taper’s—and Davidson’s—most outspoken critic. In a 1983 column headlined “The Taper is Missing its Mark,” Viertel wrote of that season’s plays, “To the extent that they represent the Taper’s philosophy of drama, if it has one, they show the theatre to be cowardly, on the one hand, and simplistic on the other.” Viertel continued: “Our most visible, well financed and technically able theatre has, in fact, missed almost every exciting or important theatre development in the past few years.” As if that wasn’t damning enough, Viertel concluded: “…the Taper is quickly becoming a theatre where risk is a dirty word, where the care and feeding of a subscription audience is the central issue at hand, where actual ideas, if any, must he couched in the most digestible terms.”

Why would Gordon Davidson want this gadfly in an office next door to his own?

“I made one of those intuitive leaps that I’ve made a number of times,” Davidson explained. “Our relationship has been a healthy disagreement. I was looking for somebody who could provide me with that. I interviewed a lot of people, but they all had similar backgrounds—more academic and limited in scope and experience.”

The hiring process began during an interview Viertel was conducting with Davidson about the Taper’s fifth repertory season. “We couldn’t stay on the subject,” Davidson remembered of that interview, “and Jack indicated a certain frustration with criticism and with having gone as far as he could go. We raised the whole question of whether a critic should he a critic for longer than seven years. And then that ‘click’ went off in my head.”

Viertel had been “passively looking” for an alternative to criticism. “I was burnt out as a critic,” he later confessed. “A lot of the time it was just all I could do to keep myself in the theatre.” His frustration was heightened by a somewhat theatrical family history—his grandfather had owned the French Casino in New York in the mid-1930s; his father, a novelist and playwright, also produced plays; at Harvard, Viertel was “a spear carrier” on stage opposite such fellow students as Stockard Charming and Tommy Lee Jones. After graduation, he shared a London flat with his Harvard alumni friend (and future New York Times critic) Frank Rich while both wrote novels.

But it was the seven steady years of reviewing that left Viertel eager to evolve into another theatrical milieu. “A very serious and lengthy series of conversations with Davidson” opened the possibility.

It wasn’t until the neighboring Ahmanson’s Fryer suggested that the two CTG theatres share Viertel’s talents that the contract was signed. “By his reviewing all those shows, Jack knows what our audience wants.” Fryer said. “We needed somebody who is knowledgeable in the field of musical comedy and they are very few and far between. Judging from his reviews and in conversation, he’s one of the most knowledgeable around. It’s sort of like letting the Trojan horse in, and I wouldn’t do it with just anyone.”

Viertel believes that his experiences as a critic will contribute to his work as a dramaturg. “There were situations as a critic where I would go into a play and look at the actors and director that had been assembled around a script, and say, ‘Well, l could have told them before they even went into rehearsal that this wasn’t going to work.’ And that awareness came almost completely from being a critic, from just seeing enough plays done over and over again. You begin to sense what will work and what won’t work.”

Davidson perceives Viertel’s role as Taper dramaturg to he “as close an interaction as possible, having to do with the whole evolution of what plays we do and what plays we seek out. I see him articulating what this theatre is trying to do. I want someone who will stand up to me, make me think, and be willing to challenge. I don’t need ‘yes’ men around the organization and especially in key roles of policy. After all, one aspect of dramaturgy is in-house criticism.”

But what about Viertel’s barbed commentary? Will that continue?

According to Viertel, it will: “Gordon’s been incredibly non-violent about the negative reviews I’ve written. He’s a pro and takes his lumps. There is not a kind of mainline ideology at the Taper that everything has to fit into. Gordon deals with realities that as a critic you never deal with: who’s available, what you can do when a director turns out to he the wrong director, how much freedom you have in the midst of a rehearsal period to replace him, what actors you can get, which plays you have to waive because Joe Papp has an option on them. There’s a practical labyrinth that critics really know very little about and probably should know relatively little about so as not to become embroiled in the gossip.”

And if this bold experiment doesn’t work?

“If Jack wanted to return to criticism, he could,” quipped Davidson, “or he might be tainted for life.”

But it’s doubtful, since in a 1982 review Viertel unconsciously predicted his future role in theatre: “Caught in an abyss between documentary and drama,” he wrote, “[the Taper] is willing to pander to our liberal instincts, sometimes begging for our sympathy with its political attitudes when it could win them with some well-constructed and deeply felt dramaturgy.”

Richard Stayton is a staff writer for The Los Angeles Herald Examiner.