The following essays were prompted, in great part, by Mrs. Centlivre. In 1718, the wife of Queen Anne’s cook wrote a play called A Bold Stroke for a Wife, and in 1985 I came upon this Restoration confection listed in Joseph T. Shipley’s Crown Guide to the World’s Great Plays. Intrigued by the inclusion of Mrs. Centlivre, I sifted out the other catalogued plays written by women, and discovered that Dr. Shipley numbered a grand total of 13 plays, or 1.73 percent of the World’s 750 Great Plays, as emerging from a woman’s typewriter (or plume, in the case of Mrs. Centlivre). Less disquieting was the divergent representation of women in the collection; they ran the gamut—to use a domestic metaphor with only the most ironic intentions from soup (Mary Chase) to nuts (Mae West).

Whether it was intentional or not—I suspect the latter — the Shipley guide underscored the diversity of women’s voices in playwriting while simultaneously illustrating the general critical failure to acknowledge the full extent of women’s contributions in drama. A Sunday New York Times summation of the 1984-85 theatre season, for example, failed to list a single play by a woman, in a season that included (beyond Broadway) María Irene Fornés’ The Conduct of Life, Emily Mann’s Execution of Justice and Rosalyn Drexler’s Transients Welcome.

These observations may strike many as the anachronistic belaborings of another decade, the blunt ’70s feminism that has since been displaced by a second, rounder-edged phase of feminism. If theatre in the ’80s doesn’t feel particularly feminist, it may be because this second stage is characterized by a pragmatic, let’s-get-on-with-it retrenchment which eschews yesterday’s rhetoric of sexual politics in favor of a multiplicity of other concerns.

And yet, as long as the woman’s voice remains, in large part, out of the mainstream of theatre—notwithstanding some Pulitzer pats for Marsha Norman and Beth Henley—women playwrights continue to ask the same questions in 1985 that troubled them in 1975: Is there a women’s aesthetic that is distinct from men’s? Do women censor themselves to get produced? Is there a different critical vocabulary that is used in addressing plays by women and plays on similar topics by men? What distinguishes a feminist perspective from a woman’s perspective?

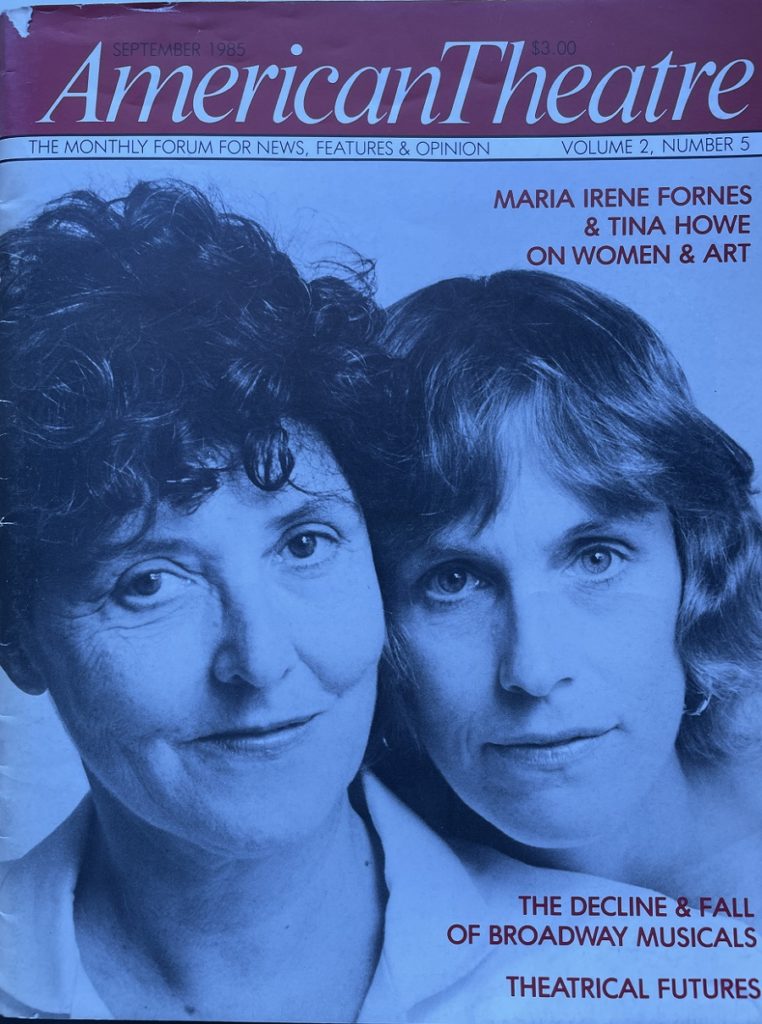

María Irene Fornés and Tina Howe have their own highly individualistic answers to such questions. As they consider in these essays how their work has reflected a woman’s perspective, some unexpected agendas are uncovered at the same time. The differences may be anticipated, to some extent, by the arrestingly distinct choices that each writer has made in forging her career as an artist.

Fornés made noise in 1977 with Fefu and Her Friends, in which eight women reunite for a weekend’s retreat and unveil their hopes, regrets, yearnings. Whatever Fornés’ intentions, the act of putting eight women on stage whose existence—for that moment—did not hinge on men was perceived by many to be a political act. Fornés’ work has since traveled an eclectic route that continually evades classification, winding from musicals light (Promenade) and dark (Santa) to, most recently, astringent examinations of poverty (Mud) and the multifarious cruelties of dictatorship (The Conduct of Life). Along the way, her plays have earned six Obie awards and incited a revealing mixture of praise and scorn. For all the awards and controversy, her prolific stream of writing continues to elude a mass audience.

In contrast, the breezy, comparatively apolitical plays of Tina Howe have captured a wide audience in a relatively short time. Painting Churches, on the other end of the social spectrum from Mud, follows the frustrated attempts of a young artist to paint a portrait of her Beacon Hill society mother and father who are, respectively, batty and senile. Painting Churches is one of this year’s most produced contemporary plays, and has renewed interest in two earlier Howe comedies, Museum, which etches the idiosyncracies of art gallery denizens, and The Art of Dining, which farcically details the operation of a restaurant.

Here then is a writer who circles the political borders of humankind, in counterpoint with another who exposes the comical underbelly of civility. Their ruminations are frank, spiky and run surprisingly contrary to expectations. Taken together, the Fornés and Howe essays become at once an artist’s protest against expectations; a testament to the impossibility of choices; and a plangent articulation of the issues surrounding women’s sensibility in playwriting.

Jan Stuart

Tina Howe: Covering Our Scent

My voice as a woman playwright has had a range that only my earliest fans know about. My first two plays, The Nest and Birth and After Birth were so radically female in point of view, I left the critics in shock and was fired by my own agent. Not that I was deliberately trying to provoke anyone. I was a serene innocent who didn’t know any better. The feminist rhetoric had barely been articulated, and being such a loner, I wouldn’t have heard it anyway. I was simply putting my own antic vision on the stage of what it meant to be a woman. That the critics were horrified was astounding to me; that the early feminists embraced me as one of their own, even more so. That’s the blissful thing about being at the beginning of a career—you’re accountable to no one.

It also explains why one’s earliest work tends to be the most original and dangerous. God knows, putting the savagery of women battling for husbands up on a stage in 1970 was dangerous. And the production got out of hand, the high point coming when one of the actresses took off all her clothes and dove into a seven-foot-tall wedding cake to then be licked clean by her new husband. Clive Barnes simply couldn’t endure the sight. We closed in one night. To say that the audience was pitched into ecstasy was—as in most cases like this—beside the point.

Rather than be dashed by the play’s failure, something in my makeup made me determined to go out even further on a limb. Why stop at the rituals of courtship? I’d take on the sanctity of the American family itself, but with a twist. Instead of focusing on the usual parent-adolescent child relationship in which the battle lines are clear, I’d wade back to the murkier time when the child was really a child: pre-speech, smashing his toys on the kitchen floor. This was the play my former agent dismissed me for. It was rejected, often with accompanying threats and spittle, by every major theatre in the country. It still stands (except for a second act that needs more work) as my most original work. So, what was I to do if I wanted a career in the theatre? Even the fringe companies wouldn’t touch it.

The answer was obvious: regroup. Though I couldn’t curb my antic vision, at least I could move it into more palatable settings. In 1974, I made a cold and calculated study of the kinds of plays that were meeting with success. The one constant I noticed was that all were set in unlikely places: changing rooms, sanitariums, the sea shore. Audiences were desperate for escape. No wonder all the producers hated Birth and After Birth so much: I was dragging them back to reality. So I figured, “Okay, if it’s escape they want, I’ll give them the most far-fetched setting they’ve ever seen on a stage!” I thought and thought and came up with the idea of a museum, because when you think about it, nothing really happens in a museum. It’s a place where you go to look. The spoken word is of secondary importance because when you’re most moved, you tend to be silent. My objective was then to animate a museum as a museum without taking any cheap plot shots.

It was the most joyous writing experience I ever had. It was so…easy! Just spinning lovely melodies, not the kind of soul-tearing work I’d been used to doing. Though it was tricky to orchestrate with 44 characters, I finished it in six months—a record. And I didn’t sell out my voice. A grisly female aria was at the core of the play. The New York critics were mystified by it all, but at least they let us finish our run. I had found my niche at last. I would write about women as artists, eschew the slippery ground of courtship and domesticity and move up to a loftier plane.

Where my heroine talked about the strange compulsions of the creative process in Museum, the next step was to show her, in delicto flagrante. With The Art of Dining, you actually see her rendering her sauces and whipping her desserts. I have to confess it’s my favorite of my plays. I know it’s a tour de force and suffers those consequences, but the subject matter is so alive for me. I’ve always found food alternatingly terrifying and hilarious. Also, this was the play in which I finally had the courage to put my own persona on stage in the guise of poor, flapping Elizabeth Barrow Colt. I was not only reaching for greater theatricality, I was finally facing my deepest fears.

Silly girl!

The New York critics got all angry and confused again. They couldn’t perceive the design of the play. Dianne Wiest was side-splitting, but how did it all add up? My love of excess was throwing them off again. But Elizabeth’s monologues had unearthed something incredibly precious—my next play. For too long I’d been one of those dreary adults who talk about the outrageousness of their parents (“Do you know what my mother said to me when I was 42…?!”). It was high time to put them on the stage and finally forgive them. The agony was finding the right way to do it.

For three years, Painting Churches was a play about a concert pianist on the eve of her debut. Fanny and Gardner were very much the same, but the story was about their daughter coming home so she could be fitted for her recital dress. As keenly as I wanted to explore these three exotics, even more important was doing it in a way that would break new dramatic ground. I had this fixation on sandwiching a non-verbal character between two others who talked non-stop. After 12 drafts and a lot of howling at my typewriter, I realized I couldn’t do it. The girl was just so boring! When I finally hit on the idea of tossing out her piano and making her a portrait painter, I knew I had it. Finally there was an action to play—setting and breaking the pose. Ar-tistically, this was my most satisfying play. My female and aesthetic voices were fused at last. The night we opened, I was poised for a massacre. I still don’t know how I got away with it. I suspect Wally Shawn’s admonition the night The Art of Dining closed had a lot to do with it: “Endurance, Tina…endurance!”

I jumped at this invitation to articulate my place as a woman writer, so I might figure it out myself. My plays have been wildly female. There’s something very “feely” about them, yet because of Painting Churches I’m perceived as a willowy aesthete who writes about art. I’m not identified as a feminist writer, yet I’m convinced I am one—and one of the fiercer ones, to boot. Perhaps it’s the word “feminist” that throws everyone off. It tends to have sectarian connotations. Plays about women artists don’t seem to fall under the heading. Or perhaps—and this is a dicey thing to say, though it’s been true in my case—the only way a woman can have a career in the theatre at this time is to cover her scent a bit.

Not that we have to write like men, we just have to watch our step. Which doesn’t necessarily mean compromising ourselves as artists, though some might disagree. To me, there’s something exhilarating about the balancing act we have to pull off: it forces us to be more inventive and precise. As a result, there’s a thrilling, “now you see us, now you don’t” edginess about our work. The audience never knows when we’re suddenly going to leap up onto a higher wire and start juggling 27 flaming doves.

In my case the spectacle is further heightened by comic underpinnings. Much as I yearn to dazzle with my acrobatics, I am (and always will be) a clown. I set up these lofty expectations and then suddenly everyone’s running around with their clothes off. It happens in all my plays. The visitors in Museum tear an art work to shreds, the diners in The Art of Dining become grunting cavemen at the end of the play, and Gardner Church goes howling back to his second childhood in Painting Churches. I can’t help it. My genes cross-circuit and I end up emulating my father’s sister, Helen Howe, a diminutive Boston lady who was a screamingly funny mimic. I know there’s something unnerving, almost vulgar, about a woman trying to be funny. We’re supposed to enjoy humor behind gloved hands, not leap into the spotlight with a bag full of impressions and a squirting boutonniere.

The final triumph will come, of course, when articles like this don’t have to be written, when we can address more complex issues than our gender. The tide may be turning already. The most fascinating thing is happening in my playwriting class at NYU this semester. Several of the men are writing about women while many of the women are writing about men, and in the most sympathetic, embracing ways. There’s a lure about exploring the mysteries of the opposite sex. So many of my male students have said, “I’m so glad I’m working with you because you’re a woman.” I’m always delighted to hear this, though sometimes I suffer a vestigial territoriality that murmurs, “Hey, just a minute! This is my terrain, you can’t have it!” But then I quickly feel ashamed of myself and remember we’re all in it together, which for a writer means being as open and inventive as possible.

If we can enter the shadowy landscape of the opposite sex, so much the better. I know I’m being pulled by the same curiosity. My next play will be a love story experienced from the man’s point of view. Does this signal my total collapse as a feminist? I happen to agree with Calvin Klein that nothing is more provocative than a woman wearing men’s underwear. Why not go the extra step and raid his entire closet? I have a feeling it’s the most daring thing a woman writer could attempt right now.

María Irene Fornés: Delicate and Dangerous Chances

The question of theatre—the question of art in general—is a question of honesty. I don’t see how a dishonest person could possibly write. And I don’t see how honest people could not lean in their writing to what they are, to the things they know best. If my pen is honest, I will sometimes—frequently—portray characters who, like me, are women. If my expression is honest, it is inevitable that it will often speak in a feminine way.

If I think of it, it seems natural that I would write with a woman’s perspective, but I am not aware that I am doing any such thing. I don’t sit down to write to make a point about women if the central character of my play is a woman, any more than I intend to make a point about men when I write a play like The Danube, where the central character is a young man. The Danube is, in fact, a play about the end of the world.

Often, there are misunderstandings about my work because it is expected that as a woman I must be putting women in traditional or untraditional roles, or roles of subservience or subjugation or dominance, to illustrate those themes. Or when one of my women characters is portrayed in a position of work or leisure, certain assumptions or simplifications are made about the character which might be quite the opposite of what is presented in the play. When those contradictions occur, the critics never question their initial premise. Instead, they see it as a fault in the play.

The same thing happens if you have a non-white character or actor in a play. Immediately people assume the play is dealing with racial questions. One can almost hear those people asking, “If you want to deal with a ‘person,’ why don’t you put a ‘person’ on stage?”

In my play Mud, the character Mae works very hard. She earns the little money that comes into the house. The two men don’t earn money. That is not, traditionally, a woman’s position. The work that she does is ironing, which is traditionally viewed as a woman’s job, although Chinese laundrymen iron as well. It was my choice for her to iron because, in her situation, what other choices are there? She could be sewing. I have often been told that in Mud I have written a play about women’s subservience, by virtue of Mae’s job. While it is true that ironing is work that women do, the play also makes it very clear that Mae is willful and strongminded, and that the men in the play accept her as such and love her without making any attempt to undermine her strength. These people are too poor to indulge in bizarre ego games. They have a reality to deal with, which is poverty. That is the way things have worked out for them. The concepts of sex roles and role playing are a luxury, an indulgence that requires a degree of affluence.

The fact remains that there may very well be women whose temperaments, in a very profound way, are closer to the temperaments of men. If you reversed the sexes in Mud, you would see that Mae’s nature is more male than female in terms of dominance, and that the men’s natures are more female in terms of tenderness and acceptance. People see the character Lloyd as violent, but if a young woman were to take a gun and shoot a man who had used her emotionally and sexually—the way Mae has used Lloyd—they would applaud. That is because there is more compassion for women in relation to emotional abandonment. But the attention to sex roles, protest against sex roles, defense against the guilt that results from that protest, all these things keep us from seeing a work with a full perspective. They prevent us from seeing characters as human beings; we see them rather as party members.

To understand Mud as being about Mae’s oppression and my more recent play The Conduct of Life about the subjugation of Latin American women is to limit the perception of those plays to a singleminded perspective. It is submitting your theatregoing activity to an imaginary regime or discipline that has little to do with the plays. I would like to be offered the freedom to deal with themes other than gender. But again, people think, what right does she have as a woman to be writing about military cruelty in Latin America?

I’m pleased that at this time in my writing I am finding expression for strong female characters who are able to speak of their longing for enlightenment and of their passions, or who make political or philosophical observations. If I were limited to writing plays to make points about women, I would feel that I was working under some sort of tyranny of the well-meaning. It is unavoidable that every choice I make comes exactly from who I am including the fact that I love to iron. I think it’s magic! Every single thing I have lived through in my life, everything I have witnessed, in some way gets into my work. The fact that I’m a woman is one of the most present things. Each day of my life something happens to me that is different from what would happen were I a man. Most of those things are rich and passionate, and I don’t refer to them by way of complaint.

As a writer, I am in an odd position in relation to feminism: radical feminists don’t consider me a feminist, but a great many people who are sympathetic consider me a feminist and see my characterizations of men as a harsh criticism. This began in1977 when I wrote Fefu and Her Friends. The idea that I was a feminist was confirmed to them when I followed Fefu with Evelyn Brown, a piece about woman’s work, based on a journal of a New England woman who worked as a servant and wrote down her household chores in great detail. After that came Eyes on the Harem, which concerned the Turkish Empire with an emphasis on the harem.

The next play I did was an erotic, turn-of-the-century piece, rather risque and naughty about sex; the men wore these white porcelain erect phalluses decorated with a blue circle like very fancy Swedish dishware, and the women wore white porcelain breasts with the nipples similarly decorated. There were a number of women who came to this play assuming that they would see feminist art, and they were horrified to find a work of such frivolity where men’s penises were paraded around with delight.

I feel myself as a woman in that I sense myself as a female organism, not as a woman in the way that society considers what I should do or think. If women suffer abuse because of the kind of organism they are—if they struggle in defense of this organism or this nature—I feel a great deal of excitement witnessing that struggle and I want to write about it. But if a woman suffers that abuse or confinement as a result of the world’s expectations, I feel compassion but I’m not as interested in writing about it. I’m not as interested in the rules of the world. I don’t like those rules and I suffer enormously from them, but the whole question is less interesting to me as a writer.

In any case, I have never set out to write in a particular manner or about a particular subject. The creative system is something so delicate and easily damaged that I would never impose anything on it. I know it has its own mind and its own will and that the system is my boss. If I think I know what I want to write about, I soon find out that I can’t write at all. But if I start writing and am patient enough, I sooner or later find something which is in the lower layers of my being, and that is the thing I should be writing about. These things are passionate yearnings that activate my writing and activate me as a person. Sometimes these things are minute, sometimes they are puzzling, but if I am patient and a good observer they will always reveal themselves to me and uncover the nature of the work I am doing, like pieces of a larger mass that crumble and reveal its nature.

The possibility of being creative depends on not being shy with one’s intimate self and not being fearful for one’s personal standing. We must take very delicate chances—delicate because they are dangerous, and delicate because they are subtle; so subtle that while we experience a personal terror it could be that no one will notice. It is this danger which in my mind is very connected to what is truly creative.

It is precisely at a time in my life when my work is following its most mysterious and personal course that it has become more political. I think this is because, although my examination is personal, my concerns are less directed at my own person. I am very happy that I have gained enough independence in my writing that the theatre around me doesn’t have so much influence as to keep me from following my own course.