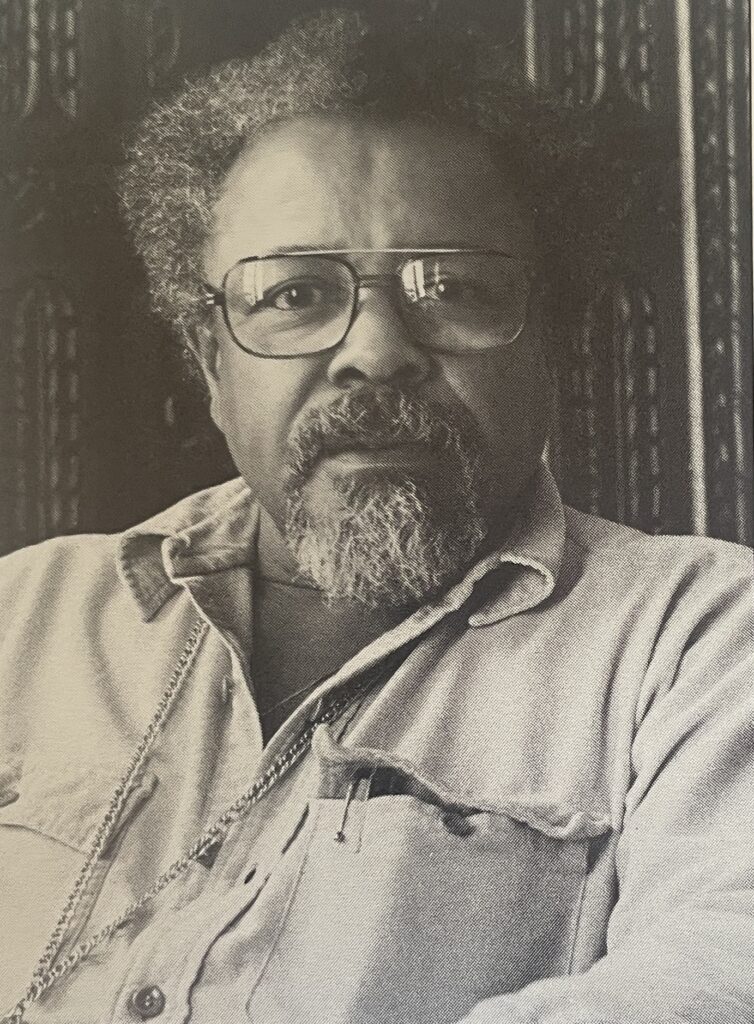

Harold Prince and Theodore Bikel are among those who have spoken for the theatre field on the prestigious National Council for the Arts. But when Lloyd Richards takes a seat on the Council this year, he becomes the first institutionally based theatre artist—the first full-fledged representative of the nonprofit professional theatre—to be included on the 26-member policy making body since the creation of the National Endowment for the Arts two decades ago.

As dean of the Yale School of Drama and artistic director of both the Yale Repertory Theatre and the O’Neill Theater Center’s National Playwrights Conference, Richards is as deeply involved in training for the theatre as he is in the development and production of new American works. The six-year appointment to the Council emphasizes yet another role-that of statesman.

Richards came first to national attention in 1959 as director of the ground-breaking Broadway production of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun; now, a generation later, another successful first play by a young black writer, August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, bears Richards’ directorial stamp. In the years between those plays, Richards observed in a recent conversation with Theatre Communications Group director Peter Zeisler, the American theatre was reshaped by the emergence of the resident theatre network, a phenomenon he refers to as a “critical margin of alternatives, which makes so much possible.”

The role of public support for the arts, the health of the theatre and its institutions, and Richards’ own aspirations for the National Council during the remaining years of the Reagan Administration were among the topics raised in the candid exchange, excerpts of which follow.

PETER ZEISLER: You’ve served as a consultant to foundations and public agencies for many years. How has support for the arts changed nationally since the NEA was established?

LLOYD RICHARDS: Prior to the Endowment—prior, really, to W. McNeil Lowry’s program of arts support by the Ford Foundation—theatre was a world of survivors. It was composed of people who had to be there. That didn’t mean that there weren’t dilettantes or hangers-on—but it meant that being in the theatre was a test, it was a measure of desire. That was a long time ago—but maybe the current situation is forcing that idea back on us.

When the NEA was established 20 years ago, it became a bellwether, at least as I have perceived it—it was a major acknowledgement to the world that our government considered the art and culture of the people of North America an important component of life in this country. There are some impressive thoughts in the legislation which established the Endowments, including one that I’ll paraphrase: While the government of the United States cannot call an artist into being, it is responsible for the support of such artists and the creation of an environment which nurtures them.

This is what the Endowment has been, and while its grants have been of major importance to arts institutions and individuals, the imprimatur of “valued artist or institution” which that support has signified has been of equal importance and value. As the NEA has grown, so has support from the private sector. Respect has been a component.

It has also been interesting to observe how significant elements in our society respond to the impulses of the highest offices in the land. When the arts are highly regarded there, attitudes and actions are emulated in foundation and business circles as well.

The NEA has changed the theatre in this country. It has assisted in decentralizing theatre and in supporting theatre artists as well as institutions. And a whole generation of Americans has grown up under this new and revolutionary concept of support.

PZ: In the early days, when the Endowment was a much smaller agency, how was its role different?

LR: The first theatre panel was a one-panel program, so that policy and grants were considered at the same time. That confirms something that I have continued to believe, which is that policy is reflected by what you choose to support: whoever controls the purse strings controls the policy. The truth is in what you support, not what vou say. There was a tremendous sense of responsibility in those days to understand the totality of theatre in this country, to get out and see it, to select from it in order to nurture growth and quality.

The NEA was a government agency, but I felt I was wanted not for my politics, not because of the political sensibilities that governed my judgment, but for my sensitivity to theatre art in this country, and my ability to articulate that and stand up for it. I would be very sad if I were to sense that politics were having an effect on the work of the Endowment.

PZ: Since this Administration took over, there’s been considerable discussion about the difference between the responsibility of federal agencies as opposed to state and local agencies. Is the NEA responsible for only national or regional institutions? What is federal, what state or local?

LR: That’s a very difficult distinction to make. I consider the National Endowment that I’ve been a part of an agency that’s concerned about the arts. How can one codify what is “state art” and what is “national art” and what is anything else?

PZ: The agency seems to be using these criteria to limit its constituency. Is this a legitimate way to do that?

LR: If it is true that the agency is using these criteria solely to achieve those ends, I do not consider it legitimate. However, all along, the Endowment has not had sufficient funds to do the job it was mandated to do. It still has the same basic mandate. If the funds are such that choices have to be made, that’s one thing. But it shouldn’t be necessary to rationalize beyond that.

PZ: What effect do you think the proposed federal cutbacks in arts support might have?

LR: How does one respond to the projection of 12-percent cuts in art funding? I think a 12-percent cut in a program that has been appropriately funded could be described as critical; a 12-percent cut in a program such as the NEA, which has by no means ever achieved appropriate funding, can only be described as catastrophic. Such a pullout of support makes an important difference because for 20 years the NEA promoted the acceptance of the arts as an integral part of the life of this country. I would hate to see an adjustment of attitude in the power structure that would in any way lessen or denigrate that respect before it was fully achieved.

The fact is that we haven’t gotten anywhere near where we need to be—and to undercut the possibilities before they’re achieved would be damaging. Damage is not always expressed in money alone; damage also comes in attitudes, in the perception of how the arts are valued. That’s where I think it’s critical.

PZ: But we can’t blame this lack of respect on the NEA, can we?

LR: No, of course we have all been subjected to that education—even we in the theatre have been educated to the idea that theatre is “play.” Even in some of our universities, drama programs have been considered extra-curricular, something for the entertainment of the community, not a serious pursuit. The problems of attitude do not all arise from the government. We share responsibility for it all up and down the line.

PZ: This year’s TCG fiscal survey, Theatre Facts 84, drew a rather devastating picture. Where do we look for help, for hope?

LR: We, the not-for-profit theatre, are very young. In spite of mistakes and setbacks, we have established a sense of direction. We have periods of growth and periods of fallbacks—but I have a compelling sense that we will survive. I believe that if everything else was gone, we’d begin to draw on cave walls again; we’d start telling stories again; we’d manage somehow. The act of theatre, of communication through theatre, is a very mystical thing, and irreplaceable.

PZ: You’ve said before that we have built the framework, the structure, the institutions, but that we haven’t yet been able to pay full attention to the artistry within them.

LR: In fact, we may not have built some of those institutions correctly; we may have incorporated into them some things that we were trying to get away from. Periodically we have to ask ourselves, are we simply the commercial theatre with protection?

The important thing, though, is that today there are stages throughout this country, there are platforms, places to be heard and seen. I was asked the difference between bringing A Raisin in the Sun to Broadway 25 years ago and bringing Ma Rainey today. The answer is that in some ways, there is no difference. There are still the same questions being asked: Will a black play work on Broadway? Is this the right time for it? Last year, I produced a 25th anniversary production of Raisin at Yale Rep, and there was talk of moving it to Broadway. It was very sad to hear the same truisms, the same formulas from 25 years ago. But then one must realize, too, that there were at least five or six productions this year of Raisin in the regional theatres. These theatres weren’t there when Raisin was originally created. So things are the same, but things are very different. The difference is in that critical margin, the not-for-profit theatre, which makes so much possible. Today there are alternatives—not the full range of alternatives that we would like, but there are alternatives.

PZ: Twenty years ago the O’Neill Playwrights Conference was started. But theatres still have not developed as creative factories, creative labs, doing indigenous creative work.

LR: Sometimes our expectations don’t match reality. There have been some recent articles in which the whole developmental process came in for condemnation, and reading them I asked myself: What is expected? The fact is that in the 20 years we have been struggling to develop a theatre system, we have turned up some exceptionally talented and interesting artists, people who have had important things to say and the theatrical imagination through which to say them. Martin Esslin told me when he worked with playwrights at the BBC that out of all the plays submitted, 10 percent were worth reading—that’s a hundred out of a thousand. Of those, 10 percent were worth doing—that’s 10 out of a thousand. Of those, 10 percent were of real value—that’s one in a thousand. I’ve found the same thing to be true. We’re talking about finding an artist and developing him into a craftsman as well. That is tough, fleeting, ephemeral. I consider playwriting the most difficult form of writing.

PZ: Part of the problem seems to be that theatre people are impatient. They want a Tennessee Williams to happen every week of the year.

LR: That syndrome perhaps gets us going, but it also knocks us down, because whenever that isn’t achieved, the validity of each theatre attempting new work is brought into question. When we begin to respect what we’ve done and the artists we have—and we have great talent in this country—and give them the wherewithal to do their art and the time in which to do it. we may begin to create some examples that people can look at and aspire to.

PZ: Considering the way television has reshaped the expectations of audiences, what problems does the playwright face in approaching the public?

LR: “Audience expectations” is a phrase that has always baffled me. It implies that one can comprehend a whole group of individual people. One of the most exciting things about the theatre is unpredictability. For myself, I find that the only thing I can do is what I feel passionate about, and then look around. If there’s anybody there, that’s the audience. If I start off trying to divine that audience and prepare for its reactions, I’m lost.

There are times, of course, when the audience may abandon me—but that doesn’t mean that what I did was not important. It just means that they didn’t perceive the same importance that I did. And that’s hard. But it happens to anyone who’s trying to create.

PZ: What are your primary concerns during your term on the National Council?

LR: The primary thing that I’ll continue to fight for is full acceptance of artists and the arts into our society. I’m excited about the theatre, about the talent I see around me. I think we’re going to go through a rough time. I don’t know how long it’s going to last. But the struggle will continue to be to find ways for our society to confirm and recognize artistic values and achievements. Respect is the first step, and dollars and opportunities flow from that.