Love at First Sight

When renowned Chinese director Ying Ruocheng began rehearsals last month for his new production, Fifteen Strings of Cash, he was a long way from his Beijing home. But he was in a theatre that he’s coming to view as a “home away from home”—the Missouri Repertory Theatre, on the campus of the University of Missouri Kansas City. The story of the theatre’s union with Ying is one of love at first sight.

UMKC is involved in a university-wide cultural exchange with the People’s Republic of China, and over the years it has hosted various visiting professors including a pianist and a doctor. Finally, in 1982, it was the Theatre Department’s turn, and Ying was invited to teach courses in Chinese theatre and acting, and to direct a play. It was apparent immediately that his contributions were invaluable, and, “We all liked him so much!” exclaims Missouri Rep dramaturg Felicia Londré. But when he directed a modern Chinese play called Family, the theatre knew that it had to have him back someday.

Family was not what anyone expected. It was not a lavish Peking opera with stylized speech and outdated ritual gestures. Presented in Ying’s own translation, the play concerned a Chinese family in the ’20s, dealing with its country’s changing political and cultural life, and the rebelliousness of its younger members against the traditions of their parents. “When we presented it, it was called a Chinese version of Dallas,” remarks Londré. In directing his Western cast in this very Eastern drama, Ying attempted to impart the way in which the Chinese characters would have moved and talked, but the proof of his success came not when the play was presented at Missouri Rep, but later when a video tape of the production was shown on Chinese television.

Six out of every 10 television viewers in the People’s Republic reportedly saw the Missouri Rep’s Family, and the next day cab drivers and waiters across the nation were talking about it. Though at first, many were dismayed to see the “tall, big-nosed people” playing Chinese characters, the final verdict was resoundingly positive: the Missouri Rep actors were overnight T.V. stars in China.

The theatre began planning for Ying’s return, which took two years to accomplish. “I have a very big agent,” he quipped, referring to his government, which still keeps a close watch on his activities. “The only agent with nuclear capabilities!” Last fall, Ying returned to Missouri as distinguished guest director, under the Fulbright Asian Scholar-in-Residence program, and once again taught classes. But the play he has undertaken to present this time is very different from Family.

Fifteen Strings of Cash is a traditional Kunchu drama by Chu Suchen, based on a 17th-century Chinese opera. The story is sheer melodrama. When a man comes home drunk and abusive, his stepdaughter leaves the house in anger. While she is gone, the man is murdered and robbed, and she is wrongly accused, tried and sentenced to die. One honest magistrate, believing in her innocence, sets out to investigate and finds the true murderer—the infamous “Lu the Rat.” Justice is served at the last moment.

Stories of unfair trials and 11th-hour reversals are popular in China, and many versions exist in their repertoire. In his production notes, Ying states that “owing to the [corrupt] judicial system in feudal China, such stories have always had significance far beyond the case in point. The present version of Fifteen Strings of Cash was a revival in the ’50s, and coming at the end of the large-scale political movements after the founding of the People’s Republic, the play conveyed a clear and unmistakable message against arbitrary jurisdiction and mistrials.”

Ying goes on to describe the instant success of the work when it was presented in the ’50s. “It caught the attention of leaders in Beijing, including the late Premiere Chou Enlai. In later years, the play was attacked by leftists as an attempt to vilify the revolution, and during the Cultural Revolution it was condemned as a ‘Poisonous Weed.'”

At Missouri Rep, the Chu Su-chen play will be done in detailed, period clothing. Once again, Ying has determined to impart a truly Chinese way of thinking and behaving to his enthusiastic company of American actors—this time a 17th-century way of thinking and behaving.

Hopes are high on the parts of both Ying and the Missouri Rep artists that his second visit will not be his last.

—Laura Ross

Living the Blues

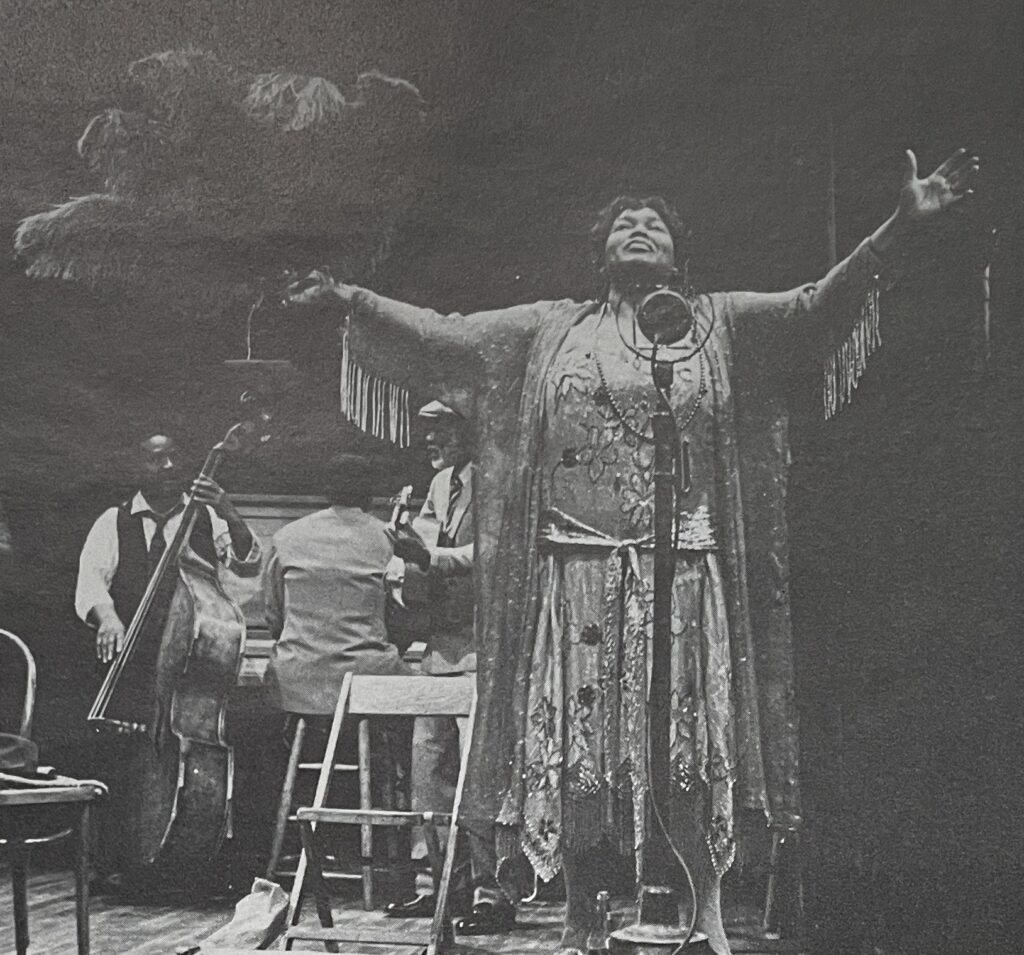

The setting is Chicago in 1927, and the characters are a group of black blues musicians presided over by the legendary singer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey. August Wilson’s play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was described by one critic as “a blues concert—as it might have been composed by Eugene O’Neill” when it premiered last April at the Yale Repertory Theatre, under the direction of artistic director Lloyd Richards. Now, after a short run at Philadelphia’s Annenberg Center beginning Sept. 20, Ma Rainey is coming to New York. Richards will again direct, and most of the Yale cast remains intact, including Theresa Merritt, above, as Ma Rainey and Charles S. Dutton as Levee, a trumpet player yearning to give up the blues to form a hot jazz band. The New York opening is slated for Oct. 11, according to producer Robert Cole.

Seattle Summit

The Olympic Arts Festival has brought the cream of world theatre to America’s doorstep—but for the past three years, Seattle’s Intiman Theatre Company has been serving its own community in much the same way. The opening of Chuo Gil (Myth Weavers) on Sept. 25 will bring the theatre of contemporary Latin America to Seattle—as well as one of that region’s foremost directors, Gustavo Tambascio. For its international production experiments in ’82 and ’83, the Intiman imported major artists from Scandinavia and West Germany.

These festival productions, the brainchild of Intiman founder-director Margaret Booker, are staged with the Intiman’s summer acting company and on a schedule and budget comparable to the theatre’s regular productions. But they have, as Booker notes, opened windows to “kinds of work and ways of working” that Seattle’s theatre community might otherwise never see.

Tambascio, this summer’s guest director, is at the helm of both the Caracas Opera Workshop, which specializes in new musical works and young talent, and the venerable Camerata des Caracas, which is fond of ancient opera forms. The 36-year-old director doubles as a university teacher and a music and opera critic for El National, Caracas’ leading newspaper.

His choice for the Intiman, Chuo Gil, is a dreamlike parable of Venezuelan back-country life by the politician-playwright Arturo Uslar-Pietri. Tambascio plans to direct an opera version of the play when he returns to Caracas in the spring.

Several members of the Chuo Gil cast have acted in all three festival productions, including the adventurous version of Strindberg’s Dreamplay mounted by the youthful Swedish director-designer team of Peter Oskarson and Peter Holm in 1982, and the controversial 1983 staging of Brecht’s In the Jungle of Cities by innovative director Christof Nel of the Hamburg Schauspielhaus. The Oscarson-Holm Dreamplay was a box office success and high point of the earlier season, but audiences and critics in the main found Nel’s “deconstructive” approach to the Brecht play less than agreeable.

“Of course we want people to appreciate these shows,” said Booker after Jungle, “but that’s not the only reason we do them. Whether you liked it or not, after seeing Jungle you knew more about what’s going on today in German theatre than if you’d read a hundred books or a thousand reviews.”

For the Intiman actors, there are other advantages of such internationalism. “If nothing else, working with these guys breaks the routine you can get into, makes you see what’s possible again,” says Peter Silbert, who has acted under Oscarson, Nel and now Tambascio. “Finding out first-hand that the way you’ve always done things isn’t the only way—that can be a very liberating experience.”

—Roger Downey

Scripts in Hand

The O’Neill Theater Center’s National Playwrights Conference just completed its 20th anniversary season, and in celebration, broadened its scope to include new works from around the world in addition to 12 American plays and five television plays. Playwrights had an opportunity to work with professional actors, directors, designers and dramaturg. Each piece was given two staged readings before an audience and the teleplays were taped and edited over an eight-day period and presented to all conference participants. Critiques followed. The international teams, representing Venezuela, Denmark, China, Australia, Russia, Argentina and the Caribbean, worked in similar O’Neill Center tradition, remaining in Waterford for a period of two-and-a-half weeks each, developing previously unproduced plays in their original language. In performance, simultaneous translation was provided. Above, Ben Siegler and Julie Boyd rehearse Cindy Lou Johnson’s Moonya, one of the 12 American scripts chosen from more than 1,400 submissions for development this past summer.

Steppenwolf Staying Put

“This theatre will not be moving to New York or San Francisco or Des Moines, despite what you may have heard or suspected,” proclaimed Jeff Perry, artistic director of Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company, at a press conference in July. He went on, “What we believe will tangibly change is that the 15-member ensemble will rely less on a 12-month residency of the entire company, and more on original company members directing and acting in Chicago productions in collaboration with a small group of carefully selected guest artists.”

The need for these reassurances was the result of Steppenwolf’s recent successes outside of its home community. Since it transferred a production of True West to New York in 1982 with great success, Steppenwolf company members have appeared in a number of critically acclaimed productions and received numerous awards. Founding member John Malkovich, who came to attention in True West, has since appeared opposite Dustin Hoffman in the recent Broadway revival of Death of a Salesman. Joan Allen won this season’s Derwent Award for a promising newcomer, for her performance in And a Nightingale Sang…, a Steppenwolf production that moved to the Mitzi Newhouse Theatre in New York’s Lincoln Center. (Malkovich was last year’s Derwent recipient, for True West.) And Balm in Gilead, a Steppenwolf co-production with New York’s Circle Repertory Company, has brought six company members to New York for an indeterminate period—the play is scheduled to move to the newly constructed Minetta Lane Theatre on Sept. 6.

All of this, combined with various film and television commitments on the parts of a number of Steppenwolf members, prompted the entire ensemble to fly to Chicago from wherever they happened to be, and hold a “reunion” on the stage of their home theatre, to discuss the present and future, and unveil production plans for 1984-85.

In his remarks, Perry insisted that “it is imperative that Chicago remain the base of our operations,” because of both economic concerns and the need for freedom to create, away from “overwhelming economic and media pressure.”

He also stressed that the company’s success in New York has helped their more ambitious projects come into being: Balm in Gilead, which includes one of the largest casts ever assembled Off Broadway, was given a running start with a $70,000 gift from Malkovich’s Death of a Salesman co-star, Dustin Hoffman.

“This group has, over the course of eight years, built a trust and knowledge among ourselves and our audience that is absolutely rare in American theatre,” he stated. He went on to detail ongoing plans for both the mainstage season and a second company, begun last year as a way to train young actors and feed the main company.

All company members have committed to act in or direct at least one of next season’s plays. The Steppenwolf’s mainstage offerings will include Simon Gray’s Stagestruck, a comic thriller directed by Tom Irwin; Chekhov’s Three Sisters, translated by Lanford Wilson and directed by Austin Pendleton; Coyote Ugly, a Midwest premiere by Lynn Siefert, directed by John Malkovich; and Caryl Churchill’s Fen, directed by Terry Kinney.

Vivid Scraps

When it opens at Off Broadway’s Jack Lawrence Theatre this month, Quilters will be billed as “a new musical.” In fact, this unusual work by Molly Newman and Barbara Damashek began life more than two years ago, premiering at the Lab of the Denver Center Theater Company and then opening its 1982 mainstage season. Since then, the play has toured extensively around the Rocky Mountain area, received a prize at the 1983 Edinburgh Festival, and been produced by other professional companies including the Pittsburgh Public Theater. New musical, indeed!

Perhaps the popularity of this simple collage of songs and stories based on the experiences of pioneer women is due to its quintessentially American nature. Just as Johnny Appleseed had his sack, these women had their scrap bags. The quilts they fashioned in bold, vivid patterns—sporting such names as “The Tree of Life” and “The Rocky Road to Kansas”—came to represent their thoughts and feelings, commemorating courtships, pregnancies, crises and rituals. Quilters explores the stories behind one woman’s “Legacy Quilt,” which in turn reveals the patchwork of her often difficult life.

En route to New York, this new production of Quilters tested its wings at the Denver Center during the month of July, moving on to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. where it can be seen through Sept 16, just before its New York opening on the 25th. Directed by Barbara Damashek, the cast includes Evalyn Baron, Marjorie Berman, Alma Cuervo, Lynn Lobban, Rosemary McNamara, Jennifer Parsons and Lenka Peterson.

Quilters is a co-production of the Denver Center, the Kennedy Center, the American National Theatre and Academy, and Brockman Seawell.

Guare’s Journey

New Playwrights’ Theatre in Washington, D.C. was bending its own rules: the final two plays of its ’83-84 season were neither new nor were they written by an emergent playwright. They did, however, represent a first.

John Guare’s Gardenia and Lydie Breeze—two parts of the playwright’s planned four-part epic journey through the 19th century—ran in repertory for the first time, offering audiences an opportunity to see the saga unfold. In fact, in “Nicholas Nickleby” fashion, on some days the plays could be seen back-to-back in one sitting (a mere five-hour undertaking as compared to Nickleby‘s eight-plus).

The plays trace the history of a Utopian commune founded on Nantucket just after the Civil War, and mingle fictional characters with historical people and events. Spanning a 20-year period and several generations, they concern the dissolution of the founder’s original, idealistic vision, and the fates of their offspring. Producing the plays in repertory was an attempt to unlock new resonances, and, in the words of one critic, “It was in combination that the reverberations and grand scale of the works was most apparent.”

No doubt Guare derived some amusement from having his works produced by an entity calling itself “New Playwrights”: He has often ironically referred to himself as “the world’s oldest ‘promising young playwright.'”

James Nicola directed Lydie Breeze and Lloyd Rose staged Gardenia. The plays also marked the swan song of New Playwrights’ founder and artistic director Harry Bagdasian, who left after 12 seasons.*

Wise Beyond Her Years

What’s in a name? In the case of the Oregon Shakespearean Festival, not the whole story. Although this season’s repertoire includes its share of Shakespeare and other classics, Ashland audiences are being treated to a liberal dollop of newer work as well, including Seascape with Sharks and Dancer, a West Coast premiere by Don Nigro, directed by Dennis Bigelow. Set in a small, decrepit beach house on Cape Cod, Seascape is an unlikely “love/hate” story involving a librarian who keeps his novel-in-progress in the refrigerator (“What if there’s a fire or something?”) and a wise-beyond-her-years renegade he saves from drowning. The pair are played by Kamella Tate, left, and Paul Vincent O’Connor. Seascape runs through Oct. 28 in the Black Swan Theatre, in repertory with Brian Friel’s Translations. Meanwhile, on the Festival’s outdoor Elizabethan Stage, The Taming of the Shrew, The Winter’s Tale and Henry VIII share the bill.

Not-So-Noble Romans

Edvard Radzinsky may not be a household name in this country, but he is one of the most successful playwrights in the Soviet Union today. His works have been produced at the Moscow Art Theatre and throughout the U.S.S.R., and his 104 Pages About Love was so popular it was presented by no fewer than 120 theatres before being turned into both a ballet and a film.

On Sept. 6, Radzinsky’s Theatre in the Time of Nero and Seneca makes its world premiere at New York’s Cocteau Repertory, under the direction of artistic director Eve Adamson in a traslation by Alma H. Law Adamson discovered the work and made arrangements to produce it on a recent cultural tour of Moscow and Leningrad sponsored by VAAP, the copyright agency of the Soviet Union. Radzinsky himself was in residence at the Cocteau during the rehearsal period.

Radzinsky, who is considered a master of the grotesque and a successor to Bulgakov, has been responsible for introducing the tragedy of conscience and the philosophical drama—neither of which has its roots in Soviet drama—to his country. Theatre in the Time of Nero and Seneca is the third part of a historical trilogy concerning the relationship of the intellectual to authority. Set over the course of one evening in Rome’s Circus Amphitheatre in 65 A.D., the action is based on the fact that Seneca, one of the greatest Roman playwrights and a man of integrity, was tutor and mentor to Nero, one of the most notorious murderers of the Roman empire. Like many contemporary political works, the play’s setting is quite distant in time and place, and yet its ultimate reverberations speak directly to the issues of our time.

The play features Craig Smith as Nero and Harris Belinsky as Seneca, and will run in repertory this season with Shakespeare’s Cymbeline, Franz Werfel’s Goat Song, L’Aiglon by Edmond Rostand and Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

Vittorio’s Visits

Continuing on the international momentum created by the recent Olympic Arts Festival in Los Angeles, the Mark Taper Forum has opened its 18th season with Viva Vittorio, a one-man show conceived, directed and performed by Vittorio Gassman. The piece was previously presented in Italy, Spain, France and South America, and makes its American premiere at the Taper through Sept. 16.

Gassman has included an eclectic mix of material: Kafka’s Report to an Academy, the account of how an ape’s desire for freedom transforms him into a world-weary man; a backstage episode from Alexandre Dumas’ Kean; Pirandello’s monodrama The Man with the Flower in His Mouth; and a soliloquy called Theatre is Bad for You, in which an aging actor’s reveries lead him to theorize about the essence of theatre itself.

The rest of the Taper season will include two more premieres, several plays new to the West Coast, and a repertory festival of classics. Mark Medoff’s new play The Hands of Its Enemy opens Sept. 22. Directed by artistic director Gordon Davidson, the play features Phyllis Frelich—who originated the lead role in Medoff’s Children of a Lesser God at the Taper and then in New York—as a playwright attempting to confront the painful secret of her childhood.

Peter Nichols’ Passion makes its West Coast debut in November, followed by the world premiere of The Woman Warrior. Adapted by Tom Cole and Joyce Chopra from books by Maxine Hong Kingston, The Woman Warrior mixes Chinese mythology with the dreams and frustrations of a young Chinese-American living in California.

Marsha Norman’s Traveler in the Dark and the Taper’s fifth Repertory Festival will complete the season next spring.

Up in the Air

Giles Maheu appears to be suspended in L’Homme rouge, a production of one of Quebec’s leading experimental companies, Carbone 14. The play will run Oct. 10-13 in New York at Playhouse 46 (St. Clement’s Church) as part of what its Canadian producer, Le Centre d’essi des auteurs of Montréal, calls a “Mini-Invasion of Québec Theatre.” The Ubu Repertory Theatre in Soho will host five readings in October of recent French Canadian plays in English translations—the authors, who will be present, include Rene Gingras, Michael Garneau, Jovette Marchessault, Normand Chaurette and Marco Micone. A seminar, “Writing for More Than One Culture,” is slated Oct. 15 with, among others, acclaimed Québec playwright-novelist Michel Tremblay. Another of Québec’s leading playwrights, Rene-Daniel Dubois, will take part in an exchange project at New Dramatists in New York, where his play Panic at Longueuil will be presented Oct. 29 with American actors under the director of Gideon Y. Schein. New Dramatist Playwright Laura Harrington completes the exchange by visiting Montréal’s Théâtre d’Aujourd’hui this month.

*The New Playwrights’ Theatre’s repertory presentation of Gardenia and Lydie Breeze was co-directed bv Lloyd Rose and James Nicola, rather than individually. And in fact Rose says the idea of doing the plays in rep was inspired by The Godfather films rather than by Nicholas Nickleby.