Voice training for actors is paradoxical: The actor must develop the voice to its utmost potential in order then to forget about it, to sacrifice it—to let it be burned through by the heat of thoughts and feelings and moods and emotions.

The voice conveys mood, emotion, attitude, opinion, confidence, conviction, restriction, inhibition and a multitude of subtle shades of meaning that influence the speaker and the listener. I call this “para-communication.” The act of speaking is composed of voice and speech, and communication is only truly successful if the information carried in the words which are formed by lips and tongue is equally balanced with the para-communication carried in the voice.

The voice reveals authentic character more than the words spoken, because the voice is formed by breath and because breath is intrinsically connected to emotion. Emotion influences psychology, personality and behavior. Together, breath and emotion create identity. Voice training for actors is not a matter of acquiring a skill. Voice is identity. Your voice says, “I am.” Voice training is centered in the awareness of breathing and liberating the full range of individual identity. Voice is made of breath, and breath gives us life; until the actor breathes as the character she or he is creating and until the actor donates his or her identity to the identity of the character, that character remains lifeless, and the words that the character speaks are implausible.

Actors must work on their voices, but the aim is not solely to be heard in the back row of the theatre. If that were so, those actors who work mainly in television or film wouldn’t need voice work. The voice is the truth thermometer. Cameras and microphones zero in on the internal truth of a performance, and if a voice is not plugged into the true and transparent inner life of instinct and emotional impulse, the truth will not be revealed. The truth may be described by a voice that delivers a kind of running commentary on what’s happening experientially, but in terms of high quality acting, description comes a poor second to revelation: Voice is the revelatory channel through which thought and feeling are conveyed. Voice is a human instrument with all the complexities that that notion implies.

By and large, the intonations and inflections of voice—the soundwaves of para-communication—are activated in the right hemisphere of the brain, while grammar, vocabulary and parts of speech are in the left. Moods and feelings emerge—in reaction to the text of a script—from the memories, experience and imagination that make us who we are, and they feed the creative imagination that will bring a character to life. These moods and feelings are registered throughout the body; the specificity of their expression in words depends a great deal on the specificity of the imagery that is engendered in memory, experience and imagination. However, although the parts of the brain that store memory and emotion and that contribute to the richness of vocal communication can determine the fullness of the information contained in the spoken word, these brain regions cannot be neatly confined to one or another hemisphere. Despite the wealth of information that advances in brain-imaging are giving us today, from a practical point of view, memory and imagination still operate from the realm of the unconscious mind, and the unconscious mind dances a merry quadrille from back to front and side to side of the brain.

From an artistic point of view, this is a fascinating time to be involved in voice and speech training. Neuroscience is shedding light on the dark pathways of brain functions that lead to speaking; the old dualistic view of mind versus body has been roundly challenged by scientists of all persuasions. “I think, therefore I am” has been scientifically trounced as a reductionist truism, and “I am, therefore I think” is the new credo. We know that the body, the senses and the emotions are vital to the intelligence of the whole self.

Ah, yes—but—we have all grown up in an educational system that has an endemic commitment to dualism. The brain, reason and rationality trump emotion and body throughout the first 20 years of our lives. We don’t know how to deal with the turmoil of our emotions—nobody offers us emotional education. Nobody suggests that speaking is a physical act engaging the senses, the emotions and the breath. The act of speaking words throughout our schooling is, thus, conditioned in an environment that exiles emotion. Words go from our rational left brain speech cortex to our mouths, barely disturbing our bodies.

As a teacher of voice for actors, my job is to re-unite brain and body experientially. The questions I ask myself daily are these: Why does the voice not do its communicative job better? Why is there such interruption and restriction in the neuro-physiological pathway between brain and body? Where is prohibition stored in the brain? Why can’t I, the teacher, intervene more directly to clear the tangled paths between emotion, breath and voice so that dramatic verbal communication is filled with authenticity?

Voice teachers seek solutions to imperfect vocal communication by spotting the physical manifestations of inhibition, prohibition and restriction, and by re-educating those bodily effects. We develop a well-stocked arsenal of exercises and strategies to remove the habits of restriction. We teach our students how to relax the throat, the jaw and the tongue, which have learned too often to clamp down on emotional expression; our students hum and ululate, shout and cry and sing through a range of many octaves; we restore breathing to the full extent of its involuntary activity from the pelvic floor to the diaphragm and the ribs. Working to release the body from its protective habits, we open up access to those storehouses in the brain that contain the elixirs of creative vocal life: emotion and imagination.

But then come the words: We can free the voice, but all too often when the voice encounters the text, the door is slammed again on freedom. The grammatical exigencies of the left hemisphere of the brain strangle the free tonal expression of the right hemisphere. Rational conditioning trumps the intelligence of body and emotion.

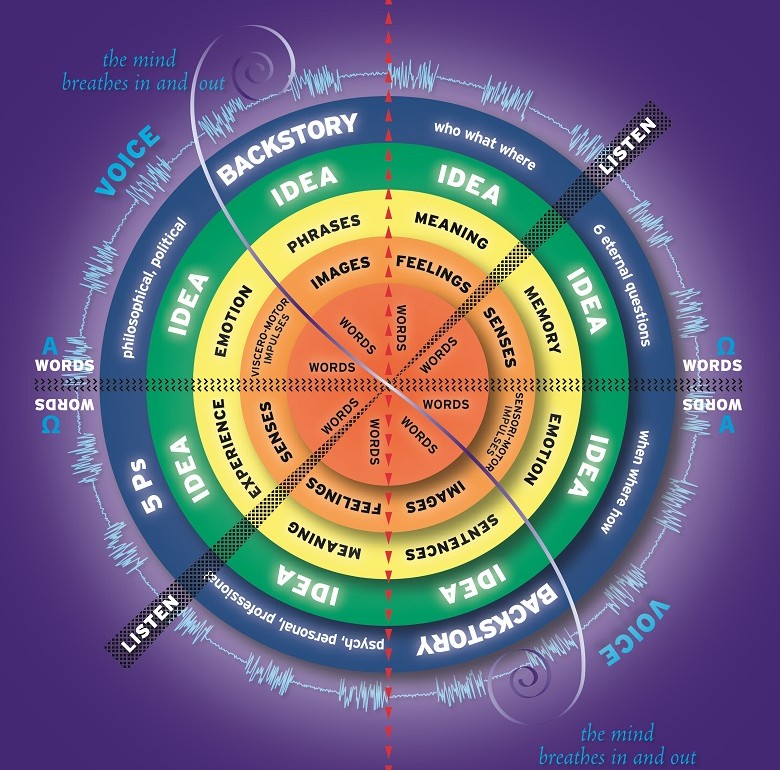

Among the many ways that actors approach a role is the essential one of creating the biography of the character—the backstory. Using a variety of working vocabularies, the actor will ask the six eternal questions of both the character and the given circumstances: who, what, why, when, where, how. Among the answers to those questions will come the knowledge of the formative events that determine the character’s behavior and actions. To guide the actor into creating as many biographical layers as possible, I offer a checklist of the 5 Ps to augment those 6 Qs: What are the psychological, the personal, the professional, the political and the philosophical facts of the character’s life?

All too often, the actor is called upon to labor cerebrally on script analysis, on biographical research, as well as on parsing and scoring, and then the actor is expected to transform that cerebration into physical and emotional action.

Words themselves, however, if embodied from the start and neurally wired into memory and emotion, will naturally engender action. Voice and text work, well understood and practiced with sensitivity, can make a critical contribution to the creative arena of acting.

I invented the Creative Daydreaming Exercise to encourage my students, as they are starting work on a text or a script, to rely less on book or Internet research coupled with written biographies of their characters, and instead to urge them to depend more on their imaginations, their memories and their emotions. If the actor begins with a trust in the power of the words themselves to generate information through the imagination—if the actor allows the words of the text to enter the body experientially through breath and voice and feelings—doors begin to open between the conscious mind and the unconscious parts of the brain that house memory, emotion and imagery.

Using the Creative Daydreaming Exercise Wheel (pictured above), the backstory emerges gradually. (Daydreaming works best in a state of relaxation, lying on the floor.) The actor begins with words dropping from the page into her or his breathing center. The words meet the vibrations of the voice in the solar plexus receiving and transmitting center, from whence they awaken emotional, sensory and visceral motor responses. The Exercise provides a guide to the exploration of the images induced by the words and their evocations of memories, experience and imagination. As words combine to make sentences and sentences combine to form meaning, ideas begin to sprout. The actor’s breath and voice are in continuous contact both with the imagination and the words (this is not silent work)—the breath and the voice are part of the voyage of discovery. Gradually, as meanings coalesce and emotional intelligence grows in response to the words, the character takes shape and the backstory is revealed.

As one learns lines, the Daydreaming Wheel enables access to the unconscious mind while the conscious mind collects data and lays down the tracks of thought and imagery that lie behind the words. This is not “memorization”—it is “learning by heart.”

Stanislavsky says: “While daydreaming, the actor visualizes the circumstances and conditions of the life of his role in all its most trivial details. He feels himself at the center of this created world; in the very thick of the role’s life. It disturbs him, makes him happy, or frightens him. He is activated. This action—even if only in his mind’s eye—is already motion, life…. Dreaming we act; acting we experience” (Sharon Marie Carnicke, Stanislavsky in Focus).

I found myself daydreaming the circumstances and conditions of transforming words on the page to words emerging from the actor’s body, and the Daydreaming chart came to my mind. I felt it might help guide the actor through the gates of the unconscious mind to the details of the backstory that lies behind the words of a script. It serves the creative process if the actor/speaker is willing to set aside an hour or two to daydream the text—to lie down on the ground, relax, breathe easily and alternate a few lines of the text to be learned with the absorption of the gentle suggestions of the chart.

Imagine, if you can, that your voice, your brain, your emotions, your breath and your five senses are all in the center of your body—somewhere below your diaphragm.

As you slowly speak words:

- let the words into the center of your breathing;

- let the words spark images (all sensory images: sights, sounds, touch, taste, smell);

- let the sensory images arouse feelings and movements in the body;

- gradually join some words together to form phrases, sentences;

- let them spark the memories, experiences, emotions of your character (who is also You…);

- let them inhabit your breath and your voice and move your body;

let ideas emerge; - gradually let the backstory reveal itself;

- answer the six eternal questions: who, where, when, what, why, how;

- and the five Ps: personal, psychological, professional, political, philosophical.

The words are gradually imprinted in your brainwaves as they are rooted in their backstory. The words you speak will be in reaction to the action of your imagery.

The details of these ingredients are what animate the breath, inform the voice and spark the intelligence that needs words.

Here are some of the reactions to the Exercise Wheel from my students:

“The chart,” says actor and voice teacher Melissa Baroni, “jump-starts my thinking in an embodied way. It’s like having a teacher by my side who moves me into different and unexpected directions. It frees me up to stay in my body and stay emotionally connected while discovering my character’s backstory.”

Adds Sheila Bandyopadhyay, an actor: “The chart taps into something before or beyond the text, something more primal and raw, which informed my playing of the words in new and unexpected ways. I felt it instantly unlocked something. I felt incredibly vulnerable and very open. It was sudden and instant, like a punch in the gut, not an intellectual revisiting of the backstory, which I had explored. It was an immediate connection to what it meant now in this present moment—in my body, not in my head.”

There remains the question of how the breath and the voice pick up and reveal emotional coloration from the stream of sensory imagery that flows back and forth from brain-to-body-to-brain and from outside-to-inside-to-outside. In working with actors one thing is clear—the involuntary activity of breathing must be free to interact with the impulses of thought, feeling and the desire to speak without being organized by external conscious muscle control.

This how question is yet to be answered satisfactorily by neuroscience, perhaps largely because it is about the cooperation of many body-mind activities, and scientists tend to be specialists in one arena or another. While the question floats in the air unanswered, I feel free to play with the provocative nomenclature of some of the regions of the brain that house memory and emotion and to imagine the role of breath in linking them to each other. My image of how gives my words new games to play throughout my body-mind.

The poetic terminology given by the classical neuroanatomists to regions of the brain is irresistible. I love the etymologies of the hippocampus, the thalamus, the amygdala, the neo-cortex and the medulla oblongata. They are the para-communicators. The shape of the hippocampus in the brain is that of a sea-horse. According to etymology, the thalamus is an “inner chamber” or even a “couch” within the chamber. Amygdala means “almond.” Cortex is the bark of a tree. And medulla means “marrow.” Plato, in Timaeus, one of his dialogues, said that the marrow was the soul and that it traveled like heat throughout our bodies by way of the bones. Perhaps there are neurons and synapses, dendrites and axons that spark from hippocampus to amygdala and thalamus and neo-cortex and that depend on the medulla oblongata to send breath to galvanize the body into speaking action.

Does it help the actor to play in the sandpit of neuroscience? I don’t know—yet—but there are new navigational stars in my quest for the holy grail of understanding how we speak. And I do know that launching oneself into the inner space of creative daydreaming opens horizons of imagination that enliven the old linear world of reason and grammar with a rush of excitement and new vision.

Kristin Linklater is a founding member and artistic director of the Linklater Center for Voice and Language. A professor of theatre arts at Columbia University, she is the author of Freeing the Natural Voice and Freeing Shakespeare’s Voice.