Playwright Christina Anderson has a penchant for historical fiction. In the Tony-nominated musical Paradise Square, the book of which she co-wrote with Larry Kirwan and Craig Lucas, African Americans and Irish immigrants in New York find their favorite watering hole, not to mention the entire nation, disrupted by the Civil War. In How to Catch Creation, four feminist artists in San Francisco see their lives intersecting with that of a queer artist from the 1960s. And pen/man/ship follows a group of African Americans on a voyage to Africa in 1896 as Jim Crow took hold in the South.

After reading the 2007 book Contested Waters by Jeff Wiltse, Anderson found another way to dive into America’s murkiest water: race. In specific, Anderson looks at the history of the desegregation of public pools. There are currently more than 300,000 such pools in the U.S., but African Americans have only been able to fully access them for the last 50 years. The fight to give Black people access to water, and the toll of that activism, are the basis for her newest play, the ripple, the wave that carried me home, commissioned by Berkeley Rep in 2014 and produced there last year, as well as at Portland Center Stage. The play is continuing its victory lap this year at Goodman Theatre, where it ran Jan. 12-Feb. 13, and will next run at Kansas City Rep, near Anderson’s hometown, March 14-April 2, and at Yale Rep April 28-May 20.

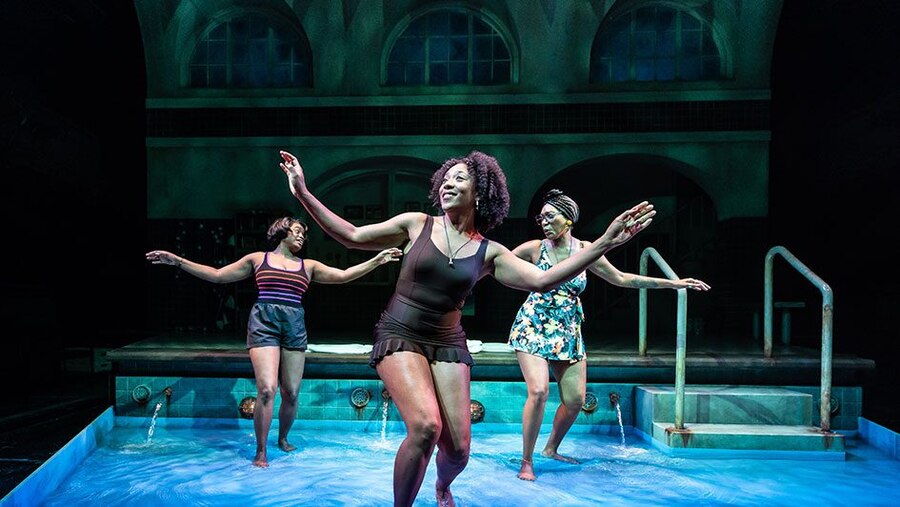

In the ripple, a woman named Janice learns from a character called Young Chipper Ambitious Black Woman that her father, Edwin, is being honored for integrating public pools in her hometown, which brings up bad memories for her. She recalls her father’s obsession over his lawsuit and a devastating incident with her mother, Helen, both of them factors that have kept her away from the water for decades. The story that unfolds addresses the unhealed wounds that racism, sexism, and segregation left on her family, and the ways that water may be able to cleanse them.

I spoke to Anderson recently about crafting new plays, activism, political efforts to ban theatre, and more.

KELUNDRA SMITH: Your plays often deal with excavating the past, specifically a Black past, for connections to today’s issues. What do you think the past can teach us about the present?

CHRISTINA ANDERSON: I have always been interested in things before my time. Even when I was a preteen and teenager, I was obsessed with movie musicals starring Doris Day, Judy Garland, and Barbra Steisand. I read Nikki Giovanni and Sonia Sanchez’s early work. As my research skills progressed, and I had access to [the JSTOR research database] in college, I would spend hours in the library. Reading made me realize how repetitive we are as human beings, particularly [pertaining to racism] in America. I was greatly affected intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually by what I was learning, and plays felt like an effective way to ask, How are these things stirring emotions in me?

What inspired you to write the ripple?

I knew I wanted to write about water as an element, but I didn’t know what I wanted to write about specifically. Then I was researching environmental injustice and I found Contested Waters, and I was completely floored. I can’t swim, my mother can’t swim, a lot of people in my family can’t swim, and it never occurred to me that a public policy could determine my access to water. That forced denial can turn things and make people believe that they’re only for white folks, so as a kid I never felt like it was a thing I was missing.

I’ve also been interested in the children of activists and the toll [that activism] takes on the family, so I wanted to make it a family drama. When I was figuring out the structure, I read Ohio State Murders and The Alexander Plays by Adrienne Kennedy, and Wallace Shawn’s plays, particularly his direct-address and solo pieces. I knew it was going to be a [play that utilizes] direct address and it was going to be about swimming.

Let’s talk about naming for a moment. In your plays, your characters’ names often indicate what they represent rather than simply being a name. Why?

I still like to have these moments in my plays that remind people we’re experiencing a theatrical piece. I don’t want anyone watching the piece to assume they know what this world is or that they know who these people are. They can see themselves in the people onstage, but I’m interested in having something be familiar, but also distanced and playful. In ripple, I knew Young Chipper would be from an upper-class Black family, and I wanted to capture culturally how that lives. But one thing that I tell directors working on this piece is that Young Chipper is absolutely a three-dimensional person in this world; she shouldn’t be an abstract figure. She’s chosen how she wants to commemorate her community, and I hope the audience laughs with her.

In the script, Helen is the one who has the idea to restore the public pool, but Edwin is painted as the hero. What are you saying about the erasure of Black women from the story of the Civil Rights Movement?

I was really thinking about the types of activism. You can have those activists, who are what I like to call disruptors, who will physically put themselves forward to protest an injustice. Then you have these people in the back rooms. I remember in college finding out about how Martin Luther King Jr. was supported on so many levels. Harry Belafonte paid for his housing; Andrew Young’s brother [Walter Young] was a dentist and did free dental work for everybody in the Civil Rights Movement. When you think about Coretta, after Martin died, she was on the phone doing fundraisers, lobbying and doing a ton of work that wasn’t on camera or in the press.

I was interested in how Black women navigate politics and activism in ways that aren’t so public but still have an immense impact. With Helen and Edwin in the play, a lot of the scenes are domestic and at home. Sometimes Helen can see the reality of the dream quicker than Edwin, but he always listens to her.

I want to touch on a couple of your other plays. I’m thinking about How to Catch Creation and pen/man/ship, both of which deal with points in history that some politicians are trying to suppress the teaching of right now. What is going on with those plays?

How to Catch Creation had productions lined up before the pandemic, but everything came to a halt. Recently, Geva Theatre in Rochester, N.Y. and Julliard produced it, and from my understanding they both went well. I don’t know what’s going to happen, but hopefully it will pick back up.

Molière in the Park did a couple of awesome online productions of pen/man/ship. Young people send me DMs on Instagram that some of the monologues have gotten them awards and into undergraduate acting programs. I’m also interested in adapting it into a screenplay, and funnily enough, that script also deals with water.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this banning that’s been happening, and what recently happened with Indecent [in Florida]. It’s a sad and wild time, but this is also history repeating itself. The arts are the first target. When politicians are trying to get elected or get on bigger political stages, the arts are the first thing they try to regulate. I hope the reaction to it can change.

What are you working on right now?

I am doing a stage adaptation of Barracoon: The Story of the Last ‘Black Cargo’, based on the book by Zora Neale Hurston. It is a commission for the Public Theater, and I’m excited to pick it back up.

What do you want your plays to do in the world? What do you want your impact to be?

When people come to see my work, I’m still purposeful and intentional in finding moments of joy and laughter. In my life, when bad things are happening, there are still those moments where miraculously I can find humor. I want people to see a good piece of theatre and see fantastic Black actors. I want people to enjoy live theatre, I want people to see parts of themselves and also see something new, or reconsider things in a new light. I want people to talk about what they’re seeing.

Kelundra Smith (she/her), a writer based in Atlanta, is a frequent contributor to this magazine.