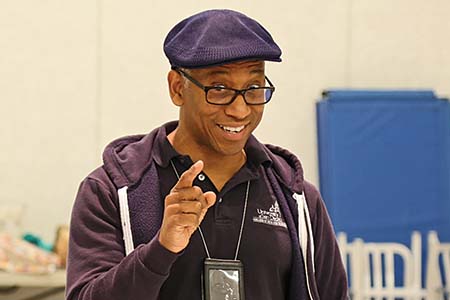

“It’s a hybrid form, which is kind of my sweet spot,” says Robert Barry Fleming, describing the series of dances and scenic transitions he staged for Karen Zacarías’s telenovela takeoff Destiny of Desire at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival earlier this year. Indeed Barry, a Cleveland-based choreographer and director, brings a deep and wide-ranging tool kit to the job, gathered from years of competitive gymnastics, dance, and acting that began at age 6 in a Kentucky State University production of A Raisin in the Sun.

To hear Fleming tell it, that tool kit isn’t ever complete.

“I’m a lifelong learner,” he says, citing as inspiration not only collaborators he’s worked with—George C. Wolfe on Jelly’s Last Jam, Robert O’Hara on Insurrection: Holding History—but a wide range of auteurs whose work he’s studied, from Pina Bausch to Robert LePage, Declan Donnellan to Ariane Mnouchkine, giving him an approach to dance and movement that is as “deeply influenced by Artaud and Brook as by Robbins and Fosse.”

It’s hardly surprising, then, that he’s found as much work as a director/choreographer as gigs doing just one or the other. While he’s helmed such straight plays as Between Riverside and Crazy and The Royale at Cleveland Play House, where he serves as associate artistic director, he recently did double duty on Caroline, or Change and Next to Normal at Tantrum Theater in Dublin, Ohio, about 2 hours southwest of Cleveland. Tantrum artistic director Daniel C. Dennis raves that Fleming’s production of Caroline was “one of the most moving experiences I’ve ever had in the theatre,” crediting it to the “loving room” Fleming creates, a place where each actor can “bring their full humanity to the performance.”

While Fleming can expound on the “black queer aesthetic and 21st-century perspective” he brings to his work, it remains rooted in story and character. With dance-heavy musicals, for instance, he says that rather than start with jazz or ballet steps, he’s “much more likely to think about social dance as a way of getting into a narrative, to help me ground it in something that doesn’t feel so abstracted, so that people have a way in that’s not alienating.”

With straight plays he says he brings “an echo of the musicals I’ve done.” Next up for him at Cleveland Play House are assignments on two non-musicals sure to require imaginative physicality: movement for Ken Ludwig’s Robin Hood romp Sherwood in February, and direction for Zacarías’s popular comedy Native Gardens in April. The bottom line, says Fleming, is that he intends all his work to be “rigorous textually and intellectually, but also very physical. There’s a lot of heart and a lot of humanity. Those are things that people don’t always think movement can release. But movement has always done that. You cannot watch Pina’s work and not feel a deep sense of the humanity.”

We shouldn’t be so shocked, after all, that movement can be moving.